HR Analytics – An ethical dilemma?

By Christoph Jentzsch | June 28, 2019

In the times of “Big Data Analytics”, the “War for Talents” and “Demographic Change” the key words HR Analytics or People Analytics seem to be ubiquitous in the realm of HR departments. Many Human Resource departments ramping up their skills on analytical technologies to deploy the golden nuggets of data they have about their own workforce. But what does HR Analytics even mean?

Mick Collins, Global Vice President, Workforce Analytics & Planning Solution Strategy at SAP SuccessFactors sets the context of HR Analytics as the following:

“The role of HR – through the management of an organization’s human capital assets – is to impact four principal outcomes: (a) generating revenue, (b) minimizing expenses, (c) mitigating risks, and (d) executing strategic plans. HR analytics is a methodology for creating insights on how investments in human capital assets contribute to the success of those four outcomes. This is done by applying statistical methods to integrated HR, talent management, financial, and operational data.” (Lalwani, 2019)

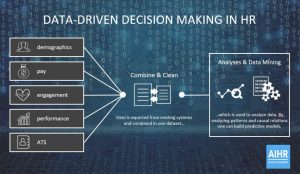

Summarized, HR Analytics is a data-driven approach to HR Management.

Figure 1: Data-Driven Decision Making in HR – Source: https://www.analyticsinhr.com/blog/what-is-hr-analytics/

So, what’s the big fuzz about it? Well, the example of Marketing Analytics, which had a revolutionary impact on the field of marketing, showcases that HR analytics is changing the way how HR departments operate tomorrow. A more data-driven approach enables HR to:

- …make better decisions using data, instead of relying on the managers gut feeling

- …move from an operational partner to a tactical, or even strategic partner (Vulpen, 2019)

- …attract more talent, by improving the hiring processes and the employee experience

- …continuously improve workforce planning through informed talent development (MicroStrategy Incorporated, 2019)

However, the increased availability of new findings and information as well as the ongoing digitalization that unlocks new opportunities to understand and interpret those information, also raises new concerns. The most critical challenges are:

- Having employees in HR functions with the right skillset to gather, manage, and report on the data

- Confidence in data quality as well as cleansing and interpretation problems

- Data privacy and compliance risks

- Ethical and moral concerns about using the data

Especially, the latter 2 aspects are up for investigation and some guidance is given on how to overcome those challenges. It is important to understand in the first place that corporate organizations collect data about their employees on very detailed level. Theoretically they could reconcile findings back down the level that identifies an individual employee. However, in the considerations of legal requirements this is not always allowed and due to the implementation of GDPR regulations, organizations are now forced to look at employee data and privacy in the same way they do for customers.

Secondly, it is crucial to understand that HR Analytics uses a range of techniques based on statistics that are incredibly valuable at the population level but they can be problematic if you use them to make a decision about an individual. (Croswell, 2019)

Figure 2: HRForecast Recruiting Analytics Dashboard source: https://www.hrforecast.de/portfolio-item/smartinsights/

This is being confirmed by Florian Fleischmann, CEO of HR Analytics Provider HRForecast as he states: “The real lever of HR Analytics is not taking place on an individual employee level, it is instead happing on a corporate macro level, when organizational processes, such as the hiring procedure or overarching talent programs are being improved.” (Fleischmann, 2019). Mr. Fleischmann is totally right, as managing people on an individual level is still a person-to-person relationship between employee and manger, which is nothing that requires a Big Data algorithm. Assuming the worst-case scenario: Job Cuts. If low-performers ought to be identified, simply line managers have to be interviewed – there is no need for a Big Data solution.

Analytics on an individual level do not bring added value but can even create harm as Mr. Fleischmann points out: “According to our experience the application of AI technology to predict for example, employee attrition rates on an individual basis can create more harm than benefit. It can cause a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the manager believes to know what team member is subject to leave and changes his behavior accordingly in a negative way”. (Fleischmann, 2019)

For that reason, HRForecast advocates for two paradigms in the ethical use and application for HR Analytics:

- Information on an employee level is only provided to the individual employee and is not shared with anyone else. “This empowers the employee to stay performant as he or she can analyze for example his or her own skill set against a benchmark of skills that are required in the future”, confirms Fleischmann.

- Information is being shared with management only on an aggregated level. The concept of “Derived Privacy” is applicable in this context as it allows enough insights to draw conclusions on a bigger scale but protects the individual employee. Given the legal regulations data on that level needs to be fully anonymized and groups smaller than 5 employees are excluded from any analysis. Fleischmann adds: “The implementation of GDPR did not affect HRForecast, as we applied those standards already pre-GDPR. Our company stands to a high ethical code of conduct, which is a key element if you want to be a successful player in the field of HR Analytics.”

In conclusion it can be stated that the application of Big Data Analytics or AI in a context of Human resources can create a huge leap in organizational transparency. However, his newly won information can cause major privacy risks for employees if not treated in reasonable fashion. To mitigate the risk of abusing the increased level of transparency an ethical code of conduct as provided by a third-party expert HRForecast needs to be applied in modern organizations. Thus, Big Data in HR can lead to an ethical dilemma, but it does not have to.

Bibliography

- Croswell, A. (2019, June 25). Why we must rethink ethics in HR analytics. Retrieved from Why we must rethink ethics in HR analytics: https://www.cultureamp.com/blog/david-green-is-right-we-must-rethink-ethics-in-hr

- Fleischmann, F. (2019, June 25). CEO HRForecast. (C. Jentzsch, Interviewer)

- Lalwani, P. (2019, April 29). What Is HR Analytics? Definition, Importance, Key Metrics, Data Requirements, and Implementation. Retrieved from What Is HR Analytics? Definition, Importance, Key Metrics, Data Requirements, and Implementation: https://www.hrtechnologist.com/articles/hr-analytics/what-is-hr-analytics/

- MicroStrategy Incorporated. (2019). HR Analytics – Everything You Need to Know. Retrieved from HR Analytics – Everything You Need to Know: https://www.microstrategy.com/us/resources/introductory-guides/hr-analytics-everything-you-need-to-know

- Vulpen, E. v. (2019). HR Analytics. Retrieved from What is HR Analytics?: https://www.analyticsinhr.com/blog/what-is-hr-analytics/