The Doctor Will Model You Now:

The Rise and Risks of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

by Dani Salah | September 23, 2018

As artificial intelligence promises to change many facets of our everyday lives, it will have perhaps no greater change than in the healthcare industry. The increase in data collected on individuals has already proven paramount in improving health outcomes, and in this infrstructure AI has a natural fit. Computing power capabilities that are orders of magnitude greater than could have been imagined just decades ago, along with increasingly complex models that can learn as well as if not better than humans, have already changed healthcare capabilities worldwide.

While the applications for AI today and in the near future hold tremendous potential, there are ethical concerns that must be considered each step of the way. Doctors, whose oaths swear them to withhold the ethical standards of medicine, may soon be pledging to abide by ethical standards of data.

Promising Applications

AI has begun demonstrating its potential to touch individuals at every point of their patient experiences. From diagnosis to surgical visit to recovery, AI and robotics can improve the efficiency and accuracy of a patient’s entire health experience. The British healthcare startup Babylon Health has this year demonstrated its product could assign correct diagnosis 75% of the time, which was 5% more accurate than the average prediction rate for human physicians. They have since raised $60 million in funding and plan to expand their algorithmic service to chatbots next (Locker, M.).

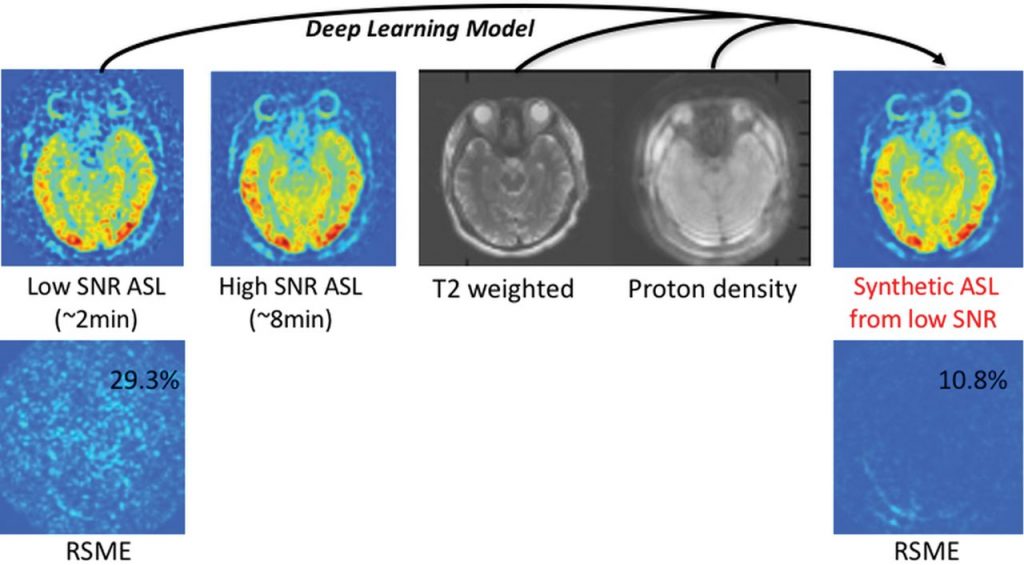

Radiology and pathology are in line for major operational shifts as AI brings new capabilities to medical imaging (G. Zaharchuk). Although nascent in its testing, results have been promising. Prediction accuracy rates often surpass human abilities here as well, and one deep learning network accurately identified breast cancer cells in 100% of the images it scanned (Bresnick, 2018).

But some areas of AI’s potential have less to do with replacing doctors and more to do with making their jobs easiers. All medical centers today are concerned with burnout, which is driving professionals across the patient experience to reduce hours, retire early or switch out of the medical career. A leading cause of this burnout is administrative requirements that don’t provide the job satisfaction many get from working in medicine. By some accounts, physicians today spend more than two thirds of their time at work handling paperwork. Increasingly sophisticated data infrastructure in the healthcare industry has done little to change the amount of time required to document a patient’s health records; it has only changed the form in which that data is documented. But automating more of such required tasks could mean that physicians have more time to spend with their patients, increasing their satisfaction in their work, and even boost accuracy of data collection and documentation (Bresnick, 2018).

Significant Risks

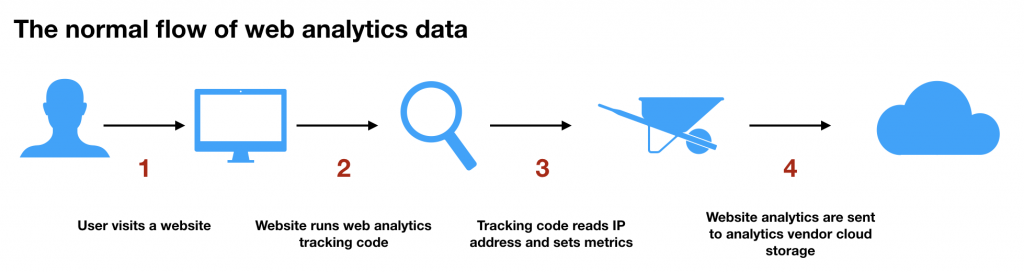

The many improvements that AI experts promise for healthcare operations certainly do not come without costs. Taking advantage of these advanced analytics possibilities requires feeding the models data – lots and lots of data. With the collection and storage of vast amounts of patient data comes the potential for data breaches, misuse of data, incorrect interpretations, and automated biases. Healthcare perhaps more than other industries necessitates that patient data is held private and secure. In fact, the emerging frameworks with which to evaluate and protect population data must be made even more stringent when the data represents extremely telling details of the health and wellness of individual people.

Works Cited

Bresnick, J. (2018). Arguing the Pros and Cons of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. [online] Health IT Analytics. Available at: https://healthitanalytics.com/news/arguing-the-pros-and-cons-of-artificial-intelligence-in-healthcare [Accessed 24 Sep. 2018].

Bresnick, J. (2018). Deep Learning Network 100% Accurate at Identifying Breast Cancer. [online] Health IT Analytics. Available at: https://healthitanalytics.com/news/deep-learning-network-100-accurate-at-identifying-breast-cancer [Accessed 24 Sep. 2018].

G. Zaharchuk, E. Gong, M. Wintermark, D. Rubin, C.P. Langlotz (2018). Deep Learning in Neuroradiology. American Journal of Neuroradiology. [online] Available at: http://www.ajnr.org/content/early/2018/02/01/ajnr.A5543 [Accessed 24 Sep. 2018].

Locker, M. (2018). Fast Company. [online] Available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/40590682/this-digital-health-startup-hopes-your-next-doctor-will-be-an-ai [Accessed 24 Sep. 2018].