Apple’s Privacy Commercial: A Deconstruction

By Danny Strockis | March 29, 2019

On March 14, Apple released their most recent advertisement, ‘Privacy on iPhone – Private Side’. Reflecting classic Apple style, it’s a powerful piece of subliminal advertising that is both timely and emotional. In 54 short seconds, Apple comments on a variety of privacy matters and not-so-subtley positions their company and products as the antidote to the surveillance economy run by the likes of Google and Facebook.

Privacy is a notoriously difficult concept to define; there’s not a single way to capture its full essence. So let’s have a closer look at Apple’s commercial and break down the privacy messages within. I’ll also touch on implications of the commercial as a whole.

0:03 – Keep out

Apple starts out by touching on the privacy of the home. A home is a hugely valued center of privacy, where people feel most comfortable. When the privacy of a home is violated, harsh reactions often follow. Examples of recent home privacy violations include the introduction of always-on personal assistants like Google Home, Amazon’s ability to deliver packages inside your home, and Google’s wifi-sniffing self-driving cars.

This scene simultaneously addresses what 1890 lawyers Warren & Brandeis have called “the right to be let alone”. When we feel that our solitude has been unwantingly violated, we often claim a privacy violation has taken place. Privacy expert Daniel Solove would identify thsee as violations of “Surveillance” or “Intrusion”.

0:08 – The eavesdropping waitress

I personally identify with this next scene; just last week I found myself pausing a conversation with my brother to let a waitress refill my water. It’s a unique way for Apple to comment on the importance of privacy in conversations, even when those conversations take place in a public forum. We often say or post something in a forum that is public, and yet maintain a certain expectation around the privacy of our words. Many online examples exist of intrusion on conversations – for instance, Facebook reading texts to serve advertisements.

0:19 – Urinals

The most laugh-out-loud scene playfully acknowledges our desire for privacy of our physical selves and bodies. It’s an often under-appreciated part of privacy in the technology, but with the advent of selfies, fitness trackers, and always-on video cameras, protection of people’s physical self is an increasingly relevant subject. Solove calls privacy violations of this nature “Exposure”.

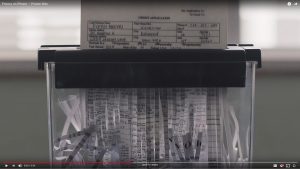

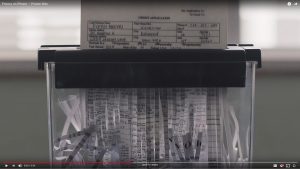

0:23 – Paper shredder

In perhaps the most direct scene, Apple succintly addresses many important topics around data privacy. The credit applicaton being shredded contains many pieces of highly sensitive personally identifiable information, which in the wrong hands could be used for identify theft and many other privacy violations. The scene plainly describes our desire to keep our information out of the wrong hands, and exercise some control over our data.

Importantly this scene also personifies our desire to have our information destroyed once it’s no longer needed. While many online businesses have made a habit of collecting historical information for eternal storage, policies in recent years have begun to enforce maximum retention periods and the right-to-be-forgotten).

0:25 – Window locks

A topic closely assoicated with privacy, especially online, is security. When a company’s databases are breached and our personal information leaked to hackers, we feel our privacy has been violated in what Solove would call “Insecurity” or “Disclosure”. In the offline world, we take great strides to ensure our security, like locking our windows or installing a security system in our home. In the online world, security is often far more out of our control; we are only as safe as the weakest security practices of the websites we visit.

0:31 – Traffic makeup

Interestingly, the final and longest segment of the commerical is perhaps the least obvious (but maybe that’s becuase I’m a male). I believe the image of a woman being watched while she applies makeup is primarily intended to describe how we don’t want creepy observers in our lives. But I like to think Apple comments on something else here – our desire to control how we are perceived in life.

Solove says that “people want to manipulate the world around them by selective disclosure of facts about themselves… they want more power to conceal information that others might use to their disadvantage.” A person’s right to control their physical appearance might be the most basic form of this desire. When the unwelcome driver in the next lane watches the businesswoman apply makeup, he steals from her the ability to control her appearance to the world.

Apple and Privacy

Apple has been heralded as a privacy and security conscious company, and industry leader amongst a sea of companies with lackluster views towards consumer privacy. A flagship example of Apple’s commitment to privacy is their early adoption of end-to-end encryption in iMessage, which protects the privacy of your written conversations on the Apple platform. Apple has also made a point of highlighting that even though they could, they have chosen not to collect information on its customers and use it for advertising or secondary uses. They like to say “their customer is not their product.”

Even still, Apple hasn’t been immune to its own privacy problems. A 2014 breach of iCloud celebrity accounts made headlines. More recently, a Facetime mistake allowed callers to view the recipient’s video feed before the recipient accepted the call. Loose rules about 3rd party application access to user information has also come under scrutiny.

Reception for Apple’s privacy commercial has been largely positive, but some have highlighted Apple’s imperfect privacy record. But I believe the more significant event here is the promotion of privacy as a topic into the forefront of consumer advertisement. Apple has long been an innovator in creative advertisements. The fact that Apple has promoted privacy so heavily shows that Apple believes privacy has reached a tipping point and has become something customers look for in purchasing decisions. This goes against previous research studies, which have shown that consumers de-priortize privacy in favor of other factors until all other factors are equal. Privacy historically takes a stark back seat to price, convenience, appeal, and functionality.

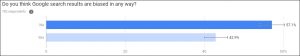

Apple seems to think privacy concern is at an all time high, and represents a business opportunity for their company. Google search trends for the “privacy” topic would say otherwise:

Only time will tell if privacy has become enough of an issue to drive a change in Apple’s bottom line. But for their part, Apple has once again done a masterful job of distilling a highly complex range of emotions into a beautiful and powerful piece of art.