Dangerous Data at Disney

Conner Brew | June 23, 2022

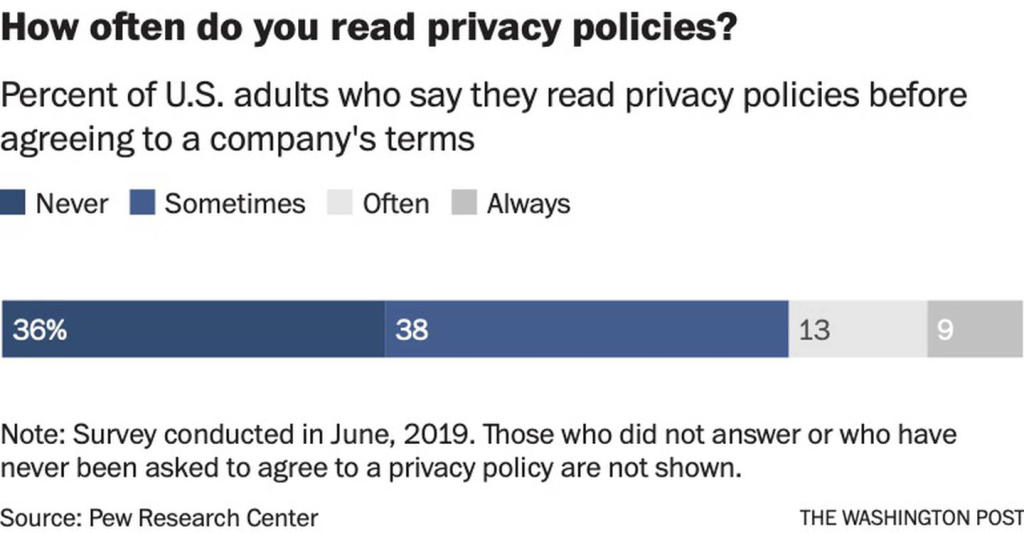

At Disney Parks, guests experience a one-of-a-kind magical experience. What many guests may not realize, however, is the extent to which their magical experience depends on the collection of their personal data. Disney Parks, such as the world-famous Disney World Resort in Orlando Florida, rely on cutting-edge technology to ensure that guests’ experiences are personalized and unforgettable. They do this through the use of the MyMagic+ mobile app, wearable Magic-Bands, and countless machine-learning-optimized shows and attractions throughout the parks.

How Does Disney Use Personal Data?

Since the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic in 2019, changes to the Disney park system have made the MyMagic mobile app absolutely necessary to the Disney experience. After purchasing park tickets, guests must register and reserve the days they plan to visit various parks – for example, if a guest purchases a 5-day pass to Disney World, they must reserve on the app the specific days during which they plan to visit individual parks like Animal Kingdom, Hollywood Studios, or Epcot. MyMagic also contains features for guests to retrieve Disney Photopass pictures taken throughout their park experiences, and allows guests to reserve fastpasses and other means of reserving space on busy attractions within the parks 1. Perhaps most practically, the app uses GPS location to provide the user with a live map of the park and instant directions to attractions of their choice, as well as the wait-times of all attractions. In the past, attraction wait times were calculated using a device that guests could carry in line with them – today, many Disney attractions use machine learning technology coupled with the location-tracking power of the MyMagic app to predict and optimize attraction wait times.

To gain maximum benefit of the MyMagic experience, guests are encouraged to purchase and wear Magic Bands. These Magic Bands can be loaded with digital payment information, digital park tickets and park reservation information, restaurant reservations, and virtually any other piece of digital information that could potentially make the Disney park experience more convenient and enjoyable. These Magic Bands use radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology to communicate with devices throughout the parks to make transactions, access reservations, and more. Disney also uses personal information stored on a guest’s Magic Band to personalize their park experience in unspecified ways: “And, if you choose to use a MagicBand, it can add a touch of magic to your vacation by unlocking special surprises, personalized just for you, throughout the Walt Disney World Resort!” 2

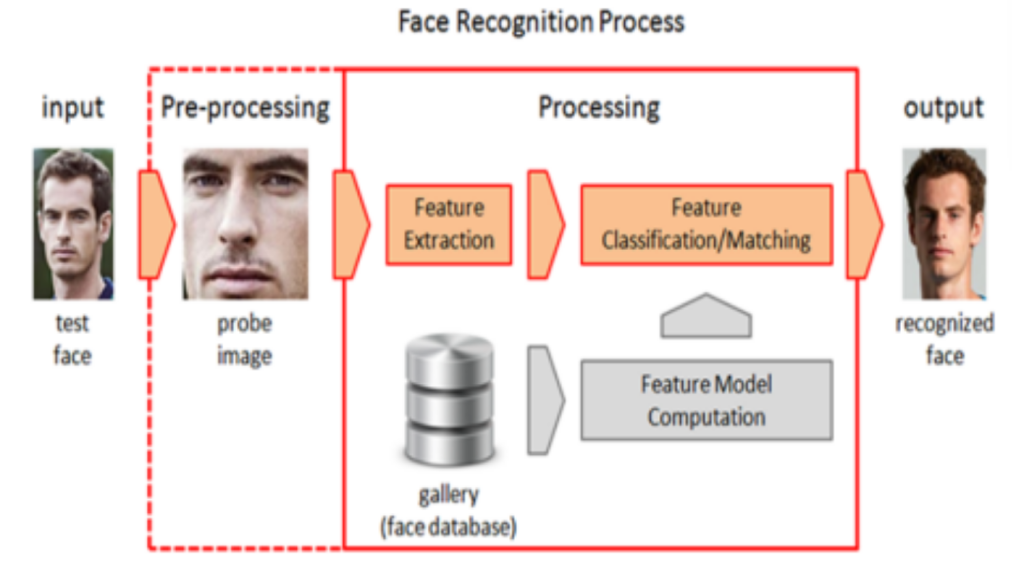

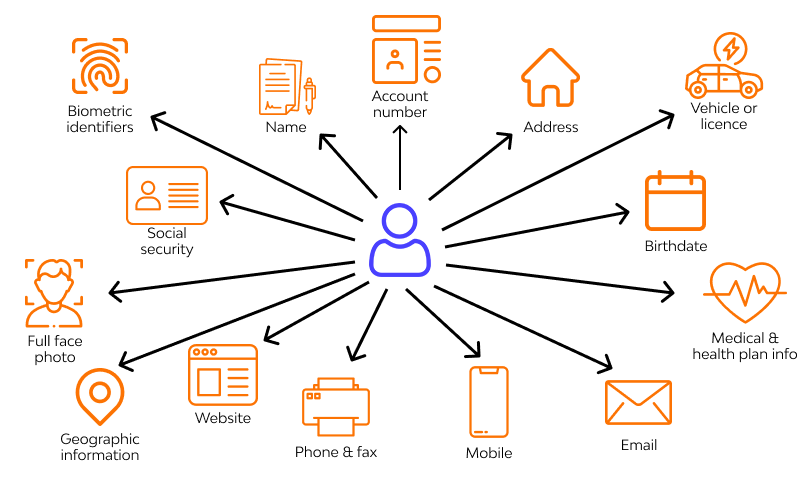

In addition to these relatively explicit means of improving and personalizing the Disney park experience through personal data collection, numerous Disney patents and studies have shown that Disney optimizes their parks using collected data that is much less explicit. For example, Disney has patented technology that allows them to identify and track individual guests using scans of their shoes 3. Disney claims that this method of guest identification and tracking is less invasive than biometric tracking methods such as facial recognition, but Solove and other privacy experts may disagree about Disney’s claim – in fact, the ability to personally identify and track individual guests through their personal data may be equally invasive regardless of the specific piece of data used to conduct said identification and tracking – that is, whether Disney is tracking shoes or faces, isn’t it still pretty invasive?

Conclusion

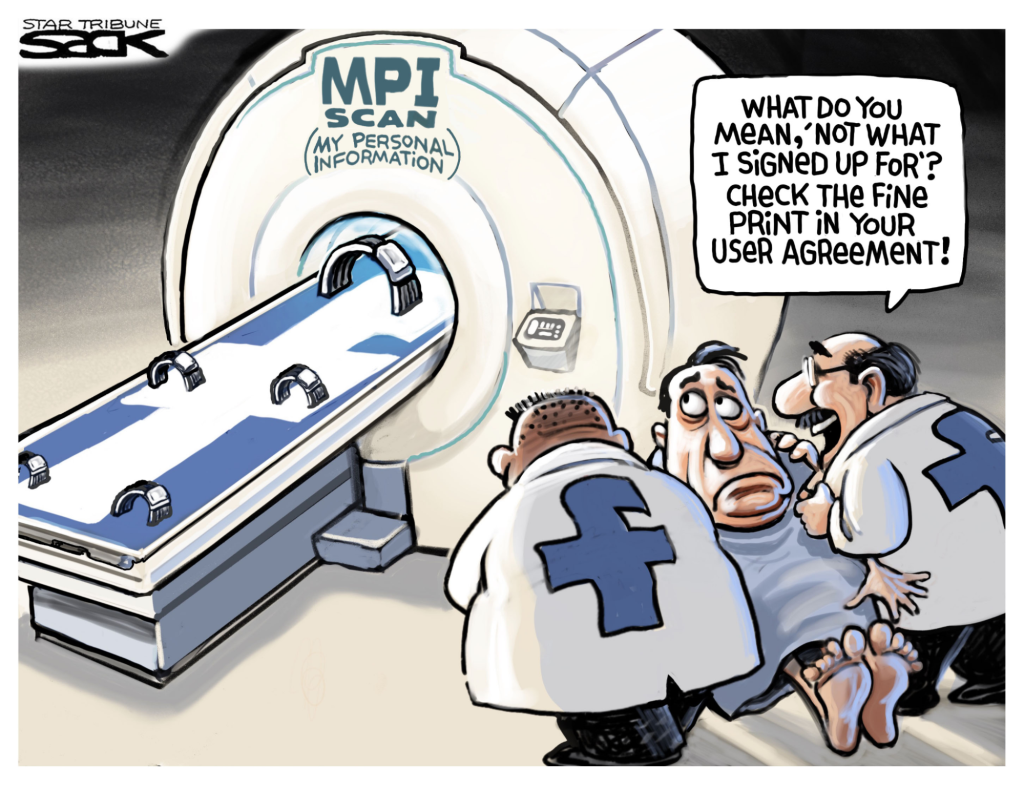

For now, Disney’s exploitation of personal data in their parks is often brushed aside. After all, who cares how personal data is collected, processed, used, and disseminated as long as it’s being used to improve the guest experience? We’ve trusted Disney to provide a safe, comfortable theme park experience since 1955 – why stop now? Here’s the bottom line: as big data collection and processing becomes more sophisticated and as the Disney park experience seeks to enhance personalization, data collection will assuredly become more invasive. Ethical concerns like beneficence, personal identification, data aggregation, and other issues will only become more prominent as the volume of exploited data at Disney continues to proliferate.

Before Disney finds itself in a corner, Disney parks should take steps to become advocates and practitioners of strong data ethics. Greater transparency, improved contextual consent, and reduction of unnecessary data collection should become the norm at Disney parks. For years, Walt Disney Imagineering (WDI) has prided itself on operating on the forefront of the cutting-edge of technology. As the use of personal data grows, WDI should strive to operate on the forefront of data ethics and privacy as well!

1 https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/vacation-planning/

2 https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/faq/my-disney-experience/my-magic-plus-privacy/

3 https://patentyogi.com/latest-patents/disney/disney-judge-shoes/

[5]

[5] [6] An episode of “How I Met Your Mother” from 2007 was rerun in 2011 with a digitally inserted cover of “Zoo Keeper” to promote the movie’s release.

[6] An episode of “How I Met Your Mother” from 2007 was rerun in 2011 with a digitally inserted cover of “Zoo Keeper” to promote the movie’s release.