Apple Vs Facebook: Who’s Right is Your Data?

by Dan Ortiz | March 12, 2021

Photo by Markus Spiske from Pexels

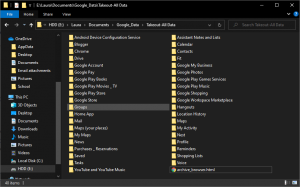

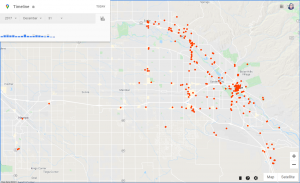

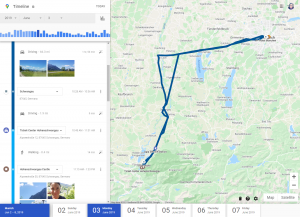

Apple and Facebook are squaring off in the public domain over user privacy. In iOS 14.5, across all devices, app tracking features will transition from opt-out to opt-in and developers will be required to provide a justification for the tracking request in regards to third party tracking (App Tracking Transparency, User Privacy, App Privacy). As much as we are concerned that an app may spy on us through our camera, or sell our location data, this permission is to mitigate concerns an app is following us throughout our digital experience and logging interactions we have with other apps. Apple’s goal is to better inform users on the information each app is collecting and provide its users with more control over their data(. It is not to end user tracking or end personalized advertisements, but to increase transparency and get users consent prior to doing so. For people who prefer highly targeted ads, they accept the tracking request. For those who find it creepy and swear Facebook is listening in on their conversations, they can deny the request. Everyone gets what they want.

In response to the upcoming iOS updates, Facebook launched a very loud, very public campaign against the new policies claiming it will financially damage small businesses by limiting the effectiveness of personalized advertisements. At the core of this disagreement is who owns the data. Facebook phrases it like this “Apple’s policy could limit your ability to use your own data to show personalized ads to people who are likely to be interested in your business”. Clearly, Apple views the control of personal data as the right of the individual user, and Facebook believes they control that right.

Facebook’s argument claims that giving users the ability to say no to cross application tracking will hurt small businesses ability to serve personalized ads to potential customers, thus increasing the small business marketing costs. Facebook has taken out full page ads and have launched a campaign (Speak Up For Small Business). Even though iOS is only 17% of the global market, it has roughly 33% of the US population and average income for an iOS user tends to be 40% higher than an Android user. iOS users are a significant market in the USA and control a significant amount of its disposable income.

However, Facebook’s argument, excluding concerns on how they calculated impact to small business, is disingenuous. Their campaign portrays this update to iOS as the death of personalized ads and the death of the small business. In reality, small businesses can still target advertisements in all data that has been uploaded to Facebook from our phones directly (first party). Small businesses can still use information about us, our home town, our interests, our groups all associated with our Facebook profile. What is changing is Facebook’s ability to track iOS users across multiple applications and browsers on the device itself. It is disingenuous to claim that user generated data, on applications not owned by Facebook, is the property of another unrelated small business.

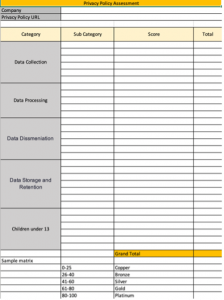

The landscape of privacy in the digital age is shifting. Apple’s policy of championing individual choice when it comes to sharing personal data, although still notify and consent, is a step in the right direction. It informs users and asks for consent directly, rather than burying it in a long user agreement document. This aligns with the GDPR requirements for lawful consent requests(source). The collection and misuse of user data is a growing concern and continues to be a topic of increased debate. Landmark legislation like CalOPPA and GDPR are increasingly redefining privacy rights of the individual. Instead of embracing these changing landscapes, Facebook chose to stand in opposition of Apple’s app-tracking feature instead of convincing us, the users, why we should allow Facebook to track us across the internet.

This conflict has exposed the real questions consumers will face when iOS is updated. When the request to track pops up as the user launches the Facebook app launches, what will they do? Will they allow tracking and vindicate Facebook’s position, or will they deny the request challenging Facebook’s current business model of tracking people all across the web?

Better yet, what decision will you make?