A market-based counterweight to AI driven polarization

By Anonymous | March 9, 2022

Stuart Russell examines the rise and existential threats of AI in his book Human Compatible. While he takes on a broad range of issues related to AI and Machine Learning, he begins the book by pointing out that AI shapes the way we live today. Take the example of a social media algorithm tasked with increasing user engagement and revenue. It’s easy to see how an AI might do this, but Russell presents an alternative theory to the problem of driving user engagement and revenue. “The solution is simply to present items that the user likes to click on, right? Wrong. The solution is to change the user’s preferences so that they become more predictable.” Russell has a more ambitious goal and continues to pull on this thread to its conclusion where algorithms tasked with one thing create other harms to achieve its end, in this case creating polarization and rage to drive engagement.

As Russell states, AI is present and a major factor in our lives today, so is the harm that it creates. One of these harms is the polarization causes through the distribution of content online such as search engines or social networks. Is there a counterweight to the current the financial incentives of content distribution networks, such as search engines and social networks, that could help create a less polarized society?

The United States is more polarized than ever, and the pandemic is only making things worse. Just before the 2020 presidential election, “roughly 8 in 10 registered voters in both camps said their differences with the other side were about core American values, and roughly 9 in 10—again in both camps—worried that a victory by the other would lead to “lasting harm” to the United States.” (Dimock & Wike, 2021) This gap only widened over the summer leading to Dimock and Wike concluding that the US has become more polarized more quickly than the rest of the world.

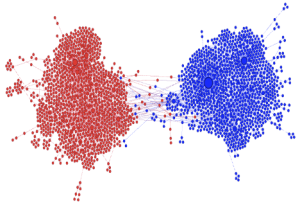

(Kumar, Jiang, Jung, Lou, & Leskovec, MIS2: Misinformation and Misbehavior Mining on the Web)

While we cannot attribute all of this to the rise of digital media, social networks, and online echo chambers, they are certainly at the center of the problem and one of the major factors. A study conducted by Hunt Allcott, Luca Braghieri, Sarah Eichmeyer, and Matthew Gentzkow published in the American Economic Review found that users became less polarized when the stopped using social media for only a month. (Allcott, Braghieri, Eichmeyer, & Gentzkow, 2020)

Much of the public focus on social media companies and polarization has focused on the legitimacy of the information presented, fake news. Freedom of speech advocates have pointed out that the label of fake news stifles speech. While many of these voices today come from the right, and much of the evidence of preferential treatment of points of view online does not support their argument, the point of view is valid and should be concerning on the face of the argument. If we accept that there is no universal truth upon which to build facts, then it follows that fake news is similarly what isn’t accepted today. This is not to say all claims online as being potentially seen as the truth in the future but the argument is that just because something is perceived to be fake or false today doesn’t mean it is fake.

This means we would need to create a system to clean up to the divisive online echo chamber not based on truth but based on perspectives presented. Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis famously said the counter to fake speech is more speech (Jr., 2011) so it is possible to create an online environment where users were presented with multiple points of view instead of the same one over and over.

Most content recommendation algorithms are essentially cluster models where the algorithm presents articles with similar content and points of view are presented to a user as articles they have liked in the past. The simple explanation being, if you like one article, you’ll also be interested in a similar one. If I like fishing articles, I’m more likely to see articles about fishing. While if I read articles about overfishing, I’m going to see articles with that perspective instead. This is a simple example of the problem, where, depending on the point of view one starts with, they only get dragged deeper into that hole. Apply this to politics and the thread of polarization is obvious.

Countering this is possible. Categorize content on multiple vectors including topic and point of view. Then present similar topics with opposing points of view to present not only more speech but more diverse speech to put the power of decision back in the hands of the human and away from the distributer. In response to the recent Joe Rogan controversy, Spotify has pledged to invest $100mm in more diverse voices but has not presented a plan to promote them on the platform to create a more well-rounded listening environment for its users. Given how actively Spotify promotes Joe Rogan, they need a plan to ensure that different voices are as easy to discover, not just available.

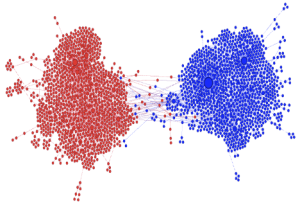

The hindrance for any private entity adopting this the same with almost any required change of a shareholder driven company, financial. As Russell pointed out, polarizing the public is profitable as it makes users more predictable and easier to keep engaged. There is a model for which a greater harm is calculated and paid for by a company which has the effect of creating a new market entirely, cap and trade.

(How cap and trade works , 2022)

Cap and trade is the idea where companies are allowed to pollute a certain amount. That creates two types of companies, those that create more pollution than they are allocated and those that produce less. Cap and trade allows polluters to buy the allocation of companies under polluting to ensure an equilibrium.

There is a similar model around speech where companies that algorithmically promote one point of view need to offset that distribution by also promoting the other point of view to the same user or group of users. This has two effects. First, it creates a financial calculous for companies who distribute content on whether they should only promote a single point of view to a subset of users, a model that has been highly profitable in the past, if they need to pay for the balance of speech. While at the same time it creates a new market of companies selling offsets who could only promote opposing points of view to specific groups than they are already receiving, points of view they are less likely to engage with, knowing they can increase their compensation for these efforts by polarizing offenders.

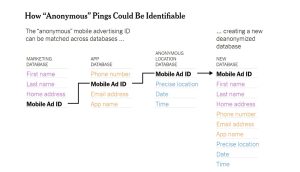

Before this goes to the logical conclusion where two companies, each promoting their opposing points of view so each equally guilty of polarization let’s talk about possibly making this work in practice. There are some very complicated issues that would make this difficult to implement like personal privacy and private companies’ strategy of keeping what they know about their users proprietary.

A social media companies presents an article to a user saying that mask mandates are create an undo negative effect on society. They would then have pushed that user towards one end of the spectrum and would be required to present an article to that user making the argument that mask mandates are necessary to slow the spread of the virus. That social media company could either present that new piece of information themselves or sell that piece of information to another company willing to create an offset to presenting it in an outside platform, creating equilibrium. Here the social media company needs to do the calculous of whether it is more profitable to continue to polarize that user on their platform or to create balance within their own walls.

This example is clearly over simplified, but ‘level of acceptance’ could be quantified, and companies could be required to create balance of opinion for specific users or subsets of users. If 80% of publications are publishing one idea, and 20% of publications are presenting the opposing idea then content distributers would be required to create an 80/20 balance for their users.

This is an imperfect starting point for creating algorithmic balance online but one to discuss an incentive and market-based approach to providing fairness to de-polarize the most polarized society at the most polarized moment in recorded history.

Bibliography

Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2020). The Welfare Effects of Social Media. American Economic Review.

Dimock , M., & Wike, R. (2021, March 29). America Is Exceptional in Its Political Divide. Retrieved from Pew Trusts: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/trust/archive/winter-2021/america-is-exceptional-in-its-political-divide

How cap and trade works. (n.d.). Retrieved from nvironmental Defense Fund: https://www.edf.org/climate/how-cap-and-trade-works

How cap and trade works . (2022). Retrieved from Environmental Defense Fund: https://www.edf.org/climate/how-cap-and-trade-works

How cap and trade works . (2022). Retrieved from Environmental Defense Fund: https://www.edf.org/climate/how-cap-and-trade-works

Jr., D. L. (2011, December). THE FIRST AMENDMENT ENCYCLOPEDIA. Retrieved from ntsu.edu: https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/940/counterspeech-doctrine#:~:text=Justice%20Brandeis%3A%20%22More%20speech%2C%20not%20enforced%20silence%22&text=%E2%80%9CIf%20there%20be%20time%20to,speech%2C%20not%20enforced%20silence.%E2%80%9D

Kumar, S., Jiang, M., Jung, T., Jle Luo, R., & Leskovec, J. (2018). MIS2: Misinformation and Misbehavior Mining on the Web. the Eleventh ACM International Conference.

Kumar, S., Jiang, M., Jung, T., Lou, R., & Leskovec, J. (n.d.). MIS2: Misinformation and Misbehavior Mining on the Web. 2018.