Risk-based Security: Should we go for Travel Convenience or Data Privacy?

By Jun Jun Peh | October 24, 2019

When the first Transportation Security Administration’s (TSA) pre-check application center opened in Indianapolis International Airport, it was the day of dream comes true for frequent travelers in the States. This is because successful applicants of the program will no longer be required to remove shoes, laptop and tiny liquid bottles from their bags anymore. In fact it is so convenient that the average time spent going pass the airport security has reduced significantly. Since then, the number of applications for TSA Pre-check increases tremendously year-over-year. Up to 2017, there has been more than 5 millions travelers enrolled in this program and there’re more than 390 application centers nationwide. The question is, what is the magic behind this ‘TSA Pre-check’ that attracts so many people to apply for it?

TSA pre-check by definition is a risk-based security system that allows trusted-travelers to walk pass the often long airport security lines via a shortcut in both line length and screening process, such as removing shoes and laptops from bags. In order to join this program, you have to pay an enrollment fee and submit to a background check and interview. After that, you will be treated like a VIP in the airport. Caveats to that: applicants have to have US citizenship / green card as a requirement to apply for it. Besides, applicants are required to provide personal details and biometrics information to TSA as part of the background check process.

This idea raised alarms among privacy advocates, in which they are concerned about the security of the information provided and its potential usage. The supposed-to-be private information will be monitored by the government for a prolonged period of time. According to Gregory Nojeim, a director at the Center for Democracy & Technology, the data could be held in database for 75 years and the database is queried by the FBI, state and local law enforcement as needed to solve crimes at which fingerprints are lifted from crime scenes. The prints may also be used for background check and info tracking as part of government’s data mining. Hence, TSA pre-check applicants are essentially trading their privacy and authorizing the government to obtain more information from them for the convenience in the airport for the rest of their lives.

Other than privacy concern, some people also challenged this program for the fact that it is only applicable by Americans. In addition to that, only elite travelers who can afford to pay the $85 USD application fees. The thought of discrimination kicks in when this risk-based security system considers only Americans are safe to join while travelers from the rest of the world are not. In fact, all travelers should be given equivalent consideration and same careful screening when it comes to customs and border protection instead of categorizing it based on nationality.

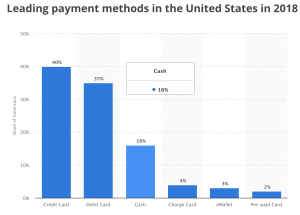

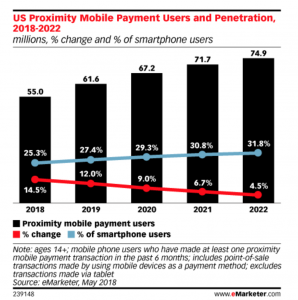

Furthermore, TSA said in a filing that the agency proceeds with hiring private companies to get more travelers into pre-check. For instance, credit card companies are providing enrollment fee rebate to get more people to sign up. In doing so, applicants are providing part of their info to these private companies as well. What worries people the most is that future implementations such as iris scan and chip implantation on travelers’ hand are being explored, for the purpose of testing easier boarding and custom clearance. If the proposal proves valid, it would cause more uproar to the privacy advocate communities.

While TSA agency claims that this risk-based security system can help CBP officers focus on potential threats and thus strengthens security screening process, the concerns that data privacy might be violated and misused cannot be ignored. Travelers who joined the program often choose to submit their privacy in exchange for travel convenience without considering implications of having their biometrics monitored. They should be given an option to opt out of this program and remove all the data permanently if they have good justification. For instance, if a green card holder decides to move out of the country, he or she should have the right to make sure data is not kept by Department of Homeland Security anymore.

From the standpoint of frequent travelers, we might be enthusiastic in making it easier and faster to get through airport security system. As we take on this path, we can only hope that the government systems are in place to protect the biometric data that we surrendered from falling into the wrong hands.

References:

1. Christopher Elliott, Oct 3rd 2013, TSA’s new Pre-Check program raises major privacy concerns. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/travel/tsas-new-pre-check-programs-raises-major-privacy-concerns/2013/10/03/ad6ee1ea-2490-11e3-ad0d-b7c8d2a594b9_story.html

2. Joe Sharkey, March 9th 2015, PreCheck Expansion Plan Raises Privacy Concern, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/10/business/precheck-expansion-plan-raises-privacy-concerns.html

3. Image 1: https://www.tsa.gov/blog/2015/01/15/reflections-risk-based-security-2014

4. Image 2: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/TSA%20FY18%20Budget.pdf