A Day in My Life According to Google: The Case for Data Advocacy

By Stephanie Seward | March 10, 2019

Recently I was sitting in an online class for the University of California-Berkeley’s data science program discussing privacy considerations. If someone from outside the program were to listen in, they would interpret our dialogue as some sort of self-help group for data scientists who fear an Orwellian future that we have worked to create. It’s an odd dichotomy potentially akin to Oppenheimer’s proclamation that he had become death, destroyer of worlds after he worked diligently to create the atomic bomb (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dus_M4sn0_I).

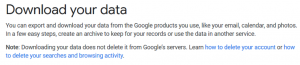

One of my fellow students mentioned as part of our in depth, perhaps somewhat paranoid, dialogue that users can download the information Google has collected on them. He said he hadn’t downloaded the data, and the rest of the group insisted that they wouldn’t want to know. It would be too terrifying.

I, however, a battle-hardened philosopher that graduated from a military school in my undergraduate days thought, I’m not scared, why not have a look? I was surprisingly naïve just four weeks ago.

What follows is my story. This is a story of curiosity, confusion, fear, and a stark understanding that data transparency and privacy concerns are prevalent, prescient, and more pervasive than I could have possibly known. This is the (slightly dramatized) story of a day in my life according to Google.

This is how you can download your data.

https://support.google.com/accounts/answer/3024190?hl=en

A normal workday according to Google

0500: Wake up, search “News”/click on a series of links/read articles about international relations

0530: Movement assessed as “driving” start point: home location end point: work location

0630: Activity assessed as “running” grid coordinate: (series of coordinates)

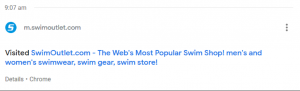

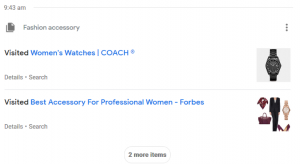

0900: Shopping, buys swimsuit, researches work fashion

1317: Uses integral calculator

1433: Researches military acquisition issues for equipment

1434: Researches information warfare

1450: Logs into maps, views area around City (name excluded for privacy), views area around post

1525: Calls husband using Google assistant

1537: Watches Game of Thrones Trailer (YouTube)

1600: Movement assessed as “driving” from work location to home location

1757: Watches Inspirational Video (YouTube)

1914-2044: Researches topics in Statistics

2147: Watches various YouTube videos including Alice in Wonderland-Chesire Cat Clip (HQ)

Lists all 568 cards in my Google Feed and annotates which I viewed

Details which Google Feed Notifications I received and which I dismissed

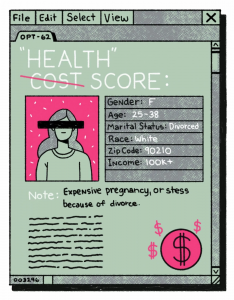

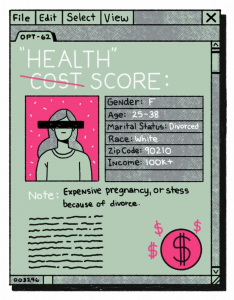

I’m not a data scientist yet, but it is very clear to me that the sheer amount of information Google has on me (about 10 GB in total) is dangerous. Google knows my interests and activities almost every minute of every day. What does Google do with all that information?

We already know that it is used in targeted advertising, to generate news stories of interests, and sometimes even in hiring practices. Is that, however, where the story ends? I don’t know, but I doubt it. I also doubt that we are advancing toward some Orwellian future in which everything about us is known by some big brother figure. We will probably fall somewhere in between.

I also know that, I am not the only one Google has about 10GB if not more information on. If you would like to view your own data, visit: https://support.google.com/accounts/answer/3024190?hl=en or to view your data online visit https://myactivity.google.com/.

Privacy considerations cannot remain in the spheres of data science and politics, we each have a role in the debate. This post is a humble attempt to drum up more interest from everyday users. Consider researching privacy concerns. Consider advocating for transparency. Consider the data, and consider the consequences.

—

Looking for more?

Here is a good place to start: https://www.wired.com/story/google-privacy-data/. This article, “The Privacy Battle to Save Google from Itself” by Lily Hay Newman is in the security section of wired.com. It details Google’s recent battles, as of late 2018, with privacy concerns. Newman discusses emphasis on transparency efforts contrasted with increased data collection on users. She talks of Google’s struggle with remaining transparent to the public and its own employees when it comes to data collection and application use. In her final remarks, Newman reiterates, “In thinking about Google’s extensive efforts to safeguard user privacy and the struggles it has faced in trying to do so, this question articulates a radical alternate paradigm ̶ one that Google seems unlikely to convene a summit over. What if the data didn’t exist at all?”