Your Health, Your Rights: medical information not covered by HIPAA

By Adam Sohn | June 26, 2020

HIPAA

HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) protects your personal medical information as possessed by a medical provider. By HIPAA, you may obtain your record, add information to your record, seek to change your record, learn who sees your information, and perhaps most importantly, exercise limited control over who sees your information.

HIPAA protection provides security enshrined in law. However, the internet and Artificial Intelligence have provided additional vectors for personal medical information to be ascertained and distributed outside of a person’s control. The implications of data release from any vector are comparable to sharing from a medical setting.

Technology Generates and Discloses Medical Information

An example of entities not bound by HIPAA for most transactions, yet dealing in medical information, is the retail sector. As customers purchase a market basket of products aligned to certain medical status, astute predictive analytics systems operated by a retailer can infer the medical status. This medical status is free from HIPAA protections as it has no origins in a medical setting. Furthermore, the status is not provided information.

Famously, the astuteness of Target’s predictive analytics was on display in 2012 when coupons for baby supplies were sent to the home of a teenage girl. While it is alarming enough that Target has a database of inferred medical information (in this case, pregnancy), Target went a step further by disclosing this information for anyone handling the teenage girl’s mail to happen upon. This triggered a public understanding of the privacy risks related to data aggregation; where mundane data becomes a building block of sensitive information.

Exploring Privacy Protections

Exploring the state of protections that do exist to prevent unwanted disclosures such as the Target case reveals a picture of a system that has room to mature.

– One way to prevent unwanted disclosure is to personally opt-out of mailed advertisements from Target, per instructions in Target’s Privacy Policy. This is an unrealistic expectation for a customer to be able to foresee such a need.

– Another method is to submit a complaint to the FTC regarding a violation of a Privacy Policy. However, Target’s Privacy Policy is vague on these matters.

Expanding the view to regulatory changes that do not yet exist, yet are in the approval progress, there is a relevant bill in Congress. CONSENT (The Customer Online Notification for Stopping Edge-provider Network Transgressions Act) was brought to the Senate in 2018 and is currently under review in the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. CONSENT would turn the tide into the public’s favor with regard to the security of Personally-Identifying Information (PII) by requiring a distinct opt-in for sharing or using PII. However, the bill is only applicable to data transacted online, which is only a portion of the relationship a consumer has with a retailer.

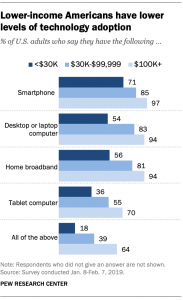

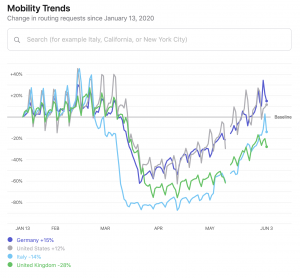

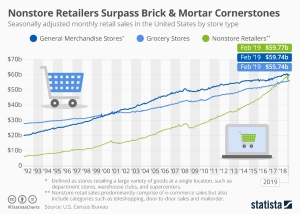

Clearly, consumer behavior is trending towards online purchases. However, brick-and-mortar purchasing can not be overlooked, as it is also increasing.

Advice to Consumers

In light of the general laxness of protections, the methods for keeping your information secure falls under the adage caveat emptor – buyer beware. For individual consumers, options to keep your information safe are:

– Only share the combination of PII and medical information in a setting where you are explicitly protected by a Privacy Policy.

– Forgo certain conveniences in order to remain obscure. This entails using cash in a brick-and-mortar store and refraining from participating in loyalty programs.

Sources

[HIPPA]

[New York Times – Shopping Habits]

[Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights]

[CONSENT]