Invisible Data: Its Impact on Ethics, Privacy and Policy

By Anil Imander | April 5, 2021

A Tale of Two Data Domains

In the year 1600, Giordano Bruno, an Italian philosopher and mystic, was charged with heresy. He was paraded through the streets of Rome, tied to a stake, and then set afire. To ensure his silence in his last minutes, a metal spike was driven through his tongue. His crime – believing that earth is another planet revolving around the sun!

Almost exactly a century later, in 1705, the queen of England knighted Isaac Newton. One of the achievements of Newton was the same one for which Giordano Bruno was burnt alive – proving that earth is another planet revolving around the sun!

Isn’t this strange! Same set of data and interpretations but completely different treatment of the subjects.

What happened?

Several things changed during the 100 years between Bruno and Newton. The predictions of Copernicus, data collection of Tycho Brahe and Kepler’s laws remained the same. Newton did come up with a better explanation of observed phenomenon using Calculus but the most important change was not in data or its interpretations. The real change was invisible – most importantly Newton had political support from royalty, the protestent sect of Christianity was more receptive to ideas challenging the church and the Bible. Many noted scientists had used Newton’s laws to understand and explain the observed world and many in the business world had found practical applications to Newton’s laws. Newton had suddenly become a rockstar in the eyes of the world.

This historical incident and thousands of such incidences highlight the fact that data has two distinct domains – Visible and Invisible.

The visible domain deals with the actual data collection, algorithm, model building and analysis. This is the focus of today’s data craze. The visible domain is the field of Big Data, Statistics, Advance Analytics, Data Science, Data Visualization and Machine Learning

The invisible domain is the human side of data. It is difficult to comprehend, not easily understood, not well defined, and is subjective. We tend to believe that data has no emotions, belief systems, culture, biases or prejudices. But data in itself is completely useless unless we, human beings, can interpret and analyze it to make decisions. But unlike data, human beings are full of emotions, cultural limitations, biases and prejudices. This human side is a critical component of the invisible data. This may come as a surprise to many readers but the invisible side of data is sometimes more critical than visible facts when it comes to making impactful decisions and policies.

The visible facts of data is a necessary condition for making effective decisions and policies but it is not sufficient unless we consider the invisible side of data.

So going back to Bruno and Newton’s example – in a way the visible data had remained the same but the invisible data was changed within the 100 years between Bruno and Newton.

You may think that we might have grown since the time of Newton – we have more data, more tools, more algorithms, advanced technologies and thousands of skilled resources. But we are still not far off from where we were – in fact the situation is even more complicated than before.

There is preponderance of data today that supports the theory that humans are responsible for climate change but almost 50 % of the people in the US do not believe that. The per capita expenditure in health care in the US is twice the amount of any developed nations in spite of a significant percentage of the people being not insured or underinsured. Yet many politicians ignore the facts on the table and are totally against incorporating any of the ideas from other developed nations into their plan whether becoming part of the “paris accord” or adopting a regulated health care system.

Why is the data itself not sufficient? There are many such examples in both business and social settings that clearly point out that along with visible facts, the invisible side of data is equally or in many cases more important than the hard facts.

Data Scientists, Data Engineers and Statisticians are well versed with visible data – raw & derived data, structures, algorithms, statistics, tools and visualization. But unless they are also well versed with the invisible side of data – they are ineffective.

The invisible side of data is the field of behavioral scientists, social scientists, philosophers, politicians, and policy makers. Unless we bring them along with the ride, just the datasets will not be sufficient.

Four challenges of Invisible Data:

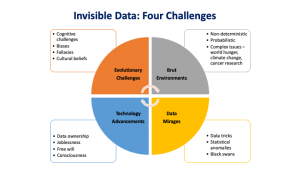

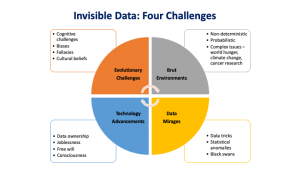

I believe that the invisible data domain has critical components that all data scientists and policymakers should be aware of. Typically, the invisible data domain is either ignored, marginalized or misunderstood. I have identified four focus areas of the invisible data domain. They are as follows.

- Human Evolutionary Limitations: Our biases, fallacies, illusions, beliefs etc.

- Brute Data Environments: Complex issues, cancer research, climate change

- Data Mirages: Black swans, statistical anomalies, data tricks etc.

- Technology Advancements: Free will, consciousness, data ownership

Human Evolutionary Limitations

Human Evolutionary Limitations

Through the process of evolution we have learnt to avoid more of Type I errors (false positives) than Type II errors (false negatives). Type I errors are costlier than Type II errors – it is better to not pick up the rope thinking that its a snake than to pick up a snake thinking that its a rope. This is just one simple example of how the brain works and creates cognitive challenges. Our thinking is riddled with behavioral fallacies. I am going to use some of the work done by Nobel Laureate, Daniel Kahneman, to discuss this topic. Kahneman shows that our brains are highly evolved to perform many tasks with great efficiency, but they are often ill-suited to accurately carry out tasks that require complex mental processing.

By exploiting these weaknesses in the way our brains process information, social media platforms, governments, media, and populist leaders, are able exercise a form of collective mind control over masses.

Two Systems

Kahneman introduces two characters of our mind:

- System 1: This operates automatically and immediately, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.

- System 2: This allocates attention to mental activities that demand dedicated attention like performing complex computations.

These two systems co-exist in the human brain and together help us navigate life; they aren’t literal or physical, but conceptual. System 1 is an intuitive system that cannot be turned off; it helps us perform most of the cognitive tasks that everyday life requires, such as identify threats, navigate our way home on familiar roads, recognize friends, and so on. System 2 can help us analyze complex problems like proving a theorem or doing crossword puzzles. System 2 takes effort and energy to engage it. System 2 is also lazy and tends to take shortcuts at the behest of System 1.

This gives rise to many cognitive challenges and fallacies. Kahneman has identified several fallacies that impact our critical thinking and make data interpretation challenging. A subset are as follows – I will be including more as part of my final project.

Cognitive Ease

Whatever is easier for System 2 is more likely to be believed. Ease arises from idea repetition, clear display, a primed idea, and even one’s own good mood. It turns out that even the repetition of a falsehood can lead people to accept it, despite knowing it’s untrue, since the concept becomes familiar and is cognitively easy to process.

Answering an Easier Question

Often when dealing with a complex or difficult issue, we transform the question into an easier one that we can answer. In other words, we use a heuristic; for example, when asked “How happy are you with life”, we answer the question, “How’s my married life or How is my job”. While these heuristics can be useful, they often lead to incorrect conclusions.

Anchors

Anchoring is a form of priming the mind with an expectation. An example are the questions: “Is the height of the tallest redwood more or less than x feet? What is your best guess about the height of the tallest redwood?” When x was 1200, answers to the second question was 844; when x was 180, the answer was 282.

Brute Data Environments

During the last solar eclipse, people travelled 100s of miles in the USA to witness the phenomenon. Thanks to the predictions of scientists, we knew exactly what time and day to expect the eclipse. Even though we have no independent capacity to verify the calculations. We tend to trust scientists.

On the other hand, the global warming scientists have been predicting the likely consequences of our emissions of industrial gases. These forecasts are critically important, because the experts see grave risks to our civilization. And yet, half the population of the USA ignores or distrusts the scientists.

Why this dichotomy?

The reason is, unlike the prediction of eclipse the climate dystopia is not immediate, it cannot predict the future as precisely as eclipse, it requires collective action at a global scale and there is no financial motivation.

If the environmentalists had predicted the Texas snowstorm of last month accurately and ahead of time to avoid its adverse impact, probably the majority of the people in the world would have started believing in global warming. But the issue of global warming is not deterministic like predicting an eclipse.

I call issues like “global warming” as issues of a brute data environment. The problem is not deterministic like predicting eclipse, it is more of a probabilistic and therefore open to interpretation. Many problems fall into this category – world hunger, cancer research, income inequality and many more.

Data Mirages

Even though we have abundance of data today, there are some inherent data problems that must not be ignored. I call them data mirages. These are statistical fallacies that can play tricks on our minds.

Survivorship Bias

Drawing conclusions from an incomplete set of data, because that data has ‘survived’ some selection criteria. When analyzing data, it’s important to ask yourself what data you don’t have. Sometimes, the full picture is obscured because the data you’ve got has survived a selection of some sort. For example, in WWII, a team was asked where the best place was to fit armour to a plane. The planes that came back from battle had bullet holes everywhere except the engine and cockpit. The team decided it was best to fit armour where there were no bullet holes, because planes shot in those places had not returned.

Cobra Effect

When an incentive produces the opposite result intended. Also known as a Perverse Incentive. Named from a historic legend, the Cobra Effect occurs when an incentive for solving a problem creates unintended negative consequences. It’s said that in the 1800s, the British Empire wanted to reduce cobra bite deaths in India. They offered a financial incentive for every cobra skin brought to them to motivate cobra hunting. But instead, people began farming them. When the government realized the incentive wasn’t working, they removed it so cobra farmers released their snakes, increasing the population. When setting incentives or goals, make sure you’re not accidentally encouraging the wrong behaviour.

Sampling Bias

Drawing conclusions from a set of data that isn’t representative of the population you’re trying to understand. A classic problem in election polling where people taking part in a poll aren’t representative of the total population, either due to self-selection or bias from the analysts. One famous example occurred in 1948 when The Chicago Tribune mistakenly predicted, based on a phone survey, that Thomas E. Dewey would become the next US president. They hadn’t considered that only a certain demographic could afford telephones, excluding entire segments of the population from their survey. Make sure to consider whether your research participants are truly representative and not subject to some sampling bias.

Technology Advancements

As per Yuval Noah Harari, one of the preeminent philosophers in Artificial Intelligence, there is a new equation that has thrown a monkey wrench into our belief system.

B * C * D = AHH

What he means is that the advancements in BioTech (B) combined with advancement in computer technology (‘C’) combined with Data (D) will provide the ability to hack human beings (AHH). Artificial intelligence is creating a new world for us where the traditional human values or human traits are becoming obsolete.

Technologies like CRISPR have already created a moral and ethical issue by providing the ability to create designer babies while technologies like Machine Learning have reignited the issue of bias by using “racist” data for training. The field of Artificial Intelligence is going to combine the two distinct domains of biology and computer technology into one.

This is going to create new challenges to the field of privacy, bias, joblessness, ethics and diversity while introducing unique issues like free will, consciousness, and the rise of machines. Some of the issues that we must consider and pay close attention to are as follows:

Transfer of authority to machines:

A couple of days ago I was sending an email using my gmail account. As soon as I hit the send button, a message popped up “did you forget the attachment?” Indeed I had forgotten to include the attachment and Google had figured that out interpreting my email text. It was scary but I was also thankful to Google! Within the last decade or more, we have come to entrust eHarmony for choosing a partner or Google to conduct search or Netflix to decide a movie for us or Amazon to recommend a book. Self-driving cars are taking over our driving needs and AI physicians are taking over the need for real doctors. We love to transfer authority and responsibility to machines. We trust the algorithms more than our own ability to make decisions for us.

Joblessness and emergence of the “useless class”:

Ever since the Industrial Revolution of the 1840s we have dealt with the idea of machines pushing people out of the job market. In the Industrial Revolution and to some extent in the Computer Revolution of 1980’s and 1990’s, the machines competed for manual skills or clerical skills. But with Artificial Intelligence, machines are also competing in cognitive and decision making skills of human beings.

Per Yuval Noah Harari – the Industrial Revolution created the proletariat class but the AI Revolution will create a “useless class.” Those who lost jobs in agriculture or handicraft during the Industrial Revolution could train themselves for Industrial jobs but the new AI Revolution is creating a class of people who will not only be unemployed but also unemployable!

Invisible Data: Impact on Ethics, Privacy and Policy

The abundance of data has created several challenges in terms of privacy, security, ethics, morals and establishing policies. Mere collection of data makes it vulnerable for hacking, aggregating and de-anonymizing. These are clear problems in the domain of visible data but these become even more complicated when we bring in invisible data in the mix. Following are few suggestions that we must explore:

Data Ownership and Usage

After the agricultural revolution, land was a key asset and decisions about its ownership were critical in managing society. After the Industrial Revolution, the focus shifted from land to factories and machines. The entire twentieth century was riddled with the ownership issue of land, factories and machines. This gave rise to two sets of political systems – liberal democracy and capitalism on one side and communism and central ownership on the other side. Today the key asset is data and decisions about its ownership and use will enable us to set the right policies. We may experience the same turmoil we went through while dealing with the issue of democracy vs communism.

The individual or the community

On most moral issues, there are two competing perspectives. One emphasizes individual rights, personal liberty, and a deference to personal choice. Stemming from John Locke and other Enlightenment thinkers of the seventeenth century, this tradition recognizes that people will have different beliefs about what is good for their lives, and it argues that the state should give them a lot of liberty to make their own choices, as long as they do not harm others.

The contrasting perspectives are those that view justice and morality through the lens of what is best for the society and perhaps even the species. Examples include vaccinations and wearing masks during a pandemic. The emphasis on seeking the greatest amount of happiness in a society even if that means trampling on the liberty of some individuals.

AI Benevolence

Today when we talk about AI, we are overwhelmed by two types of feelings. One is of awe, surprise, fascination and admiration and the other is of fear, dystopia and confusion. We tend to consider AI as both omnipotent and omniscient. There are the same adjectives we use for “God”. The AI concerns have some legitimate basis but like “God” we should also look to AI for benevolence. Long term strategies must include intense focus on using AI technology to enhance human welfare. Once we switch our focus from AI being a “big brother” to AI being a “friend” our policies, education and advancement will take a different turn.

Cross Pollination of Disciplines

As we saw already that the invisible data spans many disciplines from history to philosophy, to society to politics to behavioral science to justice and more. The new advancements in AI must include cross-pollination between humanists, social scientists, civil society, government and philosophers. Even our educational system must embrace cross pollination of disciplines, ideas and domains.

Somatic vs Germline Editing

Who decides what is right – somatic vs germline editing to cure diseases?

Somatic gene therapies involve modifying a patient’s DNA to treat or cure a disease caused by a genetic mutation. In one clinical trial, for example, scientists take blood stem cells from a patient, use CRISPR techniques to correct the genetic mutation causing them to produce defective blood cells, then infuse the “corrected” cells back into the patient, where they produce healthy hemoglobin. The treatment changes the patient’s blood cells, but not his or her sperm or eggs.

Germline human genome editing, on the other hand, alters the genome of a human embryo at its earliest stages. This may affect every cell, which means it has an impact not only on the person who may result, but possibly on his or her descendants. There are, therefore, substantial restrictions on its use.

Treatment: What is normal?

BioTech advancements like CRISPR can treat several disabilities. But many of these so-called disabilities often build character, teach acceptance, and instill resilience. They may even be correlated to creativity.

In the case of Miles Davis, the pain of sickle cell drove him to drugs and drink. It may have even driven him to his death. It also, however, may have driven him to be the creative artist who could produce his signature blue compositions.

Vincent van Gogh had either schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. So did the mathematician John Nash. People with bipolar disorder include Ernest Hemingway, Mariah Carey, Francis Ford Coppola, and hundreds of other artists and creators.

However, there was a small, although not too obvious loophole. Zoom considers this “Customer Content” to be under the user’s control, including its security, and thus it cannot guarantee that unauthorized parties will not access this content. I came to find out later that this is a major loophole that has been exploited in many instances. Although Zoom doesn’t take responsibility for this, there are many people that blame the company for not upgrading its security features. This all means that somebody would have to hack their way into my family’s private meeting in order to listen in. I believe that for most family gathering meetings the risk of this happening is not very high, so I would say it is safe to say that most family gathering zoom meetings are private as long as they are not the target of a hacker.

However, there was a small, although not too obvious loophole. Zoom considers this “Customer Content” to be under the user’s control, including its security, and thus it cannot guarantee that unauthorized parties will not access this content. I came to find out later that this is a major loophole that has been exploited in many instances. Although Zoom doesn’t take responsibility for this, there are many people that blame the company for not upgrading its security features. This all means that somebody would have to hack their way into my family’s private meeting in order to listen in. I believe that for most family gathering meetings the risk of this happening is not very high, so I would say it is safe to say that most family gathering zoom meetings are private as long as they are not the target of a hacker.

https://zoom.us/privacy

https://zoom.us/privacy

Human Evolutionary Limitations

Human Evolutionary Limitations