An Ethical Framework for Posthumous Medical Data

By Anonymous | May 28, 2021

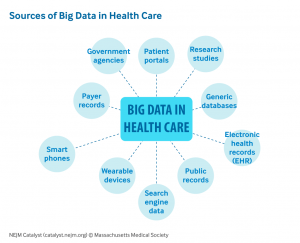

Coinciding with drastic improvements in technology and personal data collection over the previous two decades, there is an ever-growing accumulation of digital health data that individuals have access to. From electronic health reports continuously updated by your primary care provider, to direct to consumer products such as genetic sequencing tests, and even personal fitness trackers that follow an individual in real-time through their daily lives, all this information becomes a part of your health data footprint. What happens to all this information after someone passes away? Healthcare research is becoming increasingly interested in leveraging big data analysis methods on this abundance of well-documented medical data. This question brings to light the ethical concerns involving the use of posthumous patient information.

There has been much consideration regarding the ethical use of personal information from data collected while an individual is still alive. Much of this conversation revolves around maintaining consent and transparency between the parties involved, however, this becomes a different conversation when the subjects of interest are deceased. How do we proceed when we are unable to verify consent of the individual? Well the good news is that the medical community has experience regarding this issue: the physical donation of human bodies to medicine and science. There are legal and ethical frameworks in place that outline the process for donation and use of bodies and organs to medicine and research. However, part of the issues with using digital health data and electronic health records (EHRs) are the lack of rules and regulations in place, which makes it difficult for researchers to obtain large quantities of private health information for use in observational clinical research.

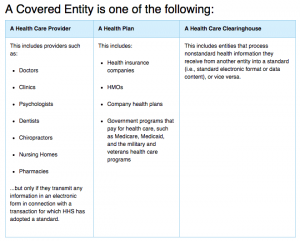

In the United States, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) regulates covered entities (i.e. health care providers) and business associates with the necessary barriers and safeguards to maintain the confidentiality of an individual’s private health information (PHI). The HIPAA Privacy Rule protects the private health information while an individual is alive and for up to 50 years after they pass away. Additionally, it outlines and describes the ways that covered entities can disclose or use PHI, including for research purposes. PHI can be used for research if the informed consent of the subject is obtained, which can be difficult to secure for posthumous data. More commonly, the existing legal policies require an institutional review board (IRB) to provide ethical approval for every research analysis that intends to be published. This current framework requires separate IRB approval for each individual research analysis and specifically prevents broad research topics, such as the analysis methods consistent with “big data”.

Research institutions can circumvent the IRB approval process using two approaches. The first approach requires the removal of PHI and identification of subjects prior to research. This alters the electronic health records to the extent that the de-identified data is no longer considered “human subject” research, which is why they do not need the approval of the IRB. This can also become dangerous because of the distortion of the data during the de-identification process, which may require the alteration of important clinical data such as demographics and diagnoses. The second approach is to essentially wait until the 50-year protected period expires, and to use the electronic health reports of patients that have died over 50-years ago. In the first approach, we compromise the integrity and accuracy of the research conducted by classifying the research as non-human subjects; in the second approach, while legal, we are compromising on ethical research principles and practices. However, we can hope to bridge the gap between these two approaches by establishing the data infrastructure necessary to conduct “big data” analysis on electronic health reports, as well as establishing an ethical code of conduct for use of posthumous patient data.

In 2019, a group of ethicists and lawyers at the Oxford Internet Institute came together to establish the first ethical code for posthumous medical data donation. This ethical code is based on five foundational principles that aim to balance the key risks for using personal health data with the promotion of the common good.

- Human dignity and respect for persons

- Promotion of the common good

- The right to Citizen Science

- Quality and good data governance

- Transparency, accountability, and integrity

Furthermore, they outline ethical conditions for the collection of the posthumous medical data donation as well as ethical practices regarding the use of the data in a research setting. They hope that their work serves to encourage the availability of personal medical data for scientific research in a safe and ethical setting.

In addition to establishing an ethical code of conduct for EHR use post mortem, researchers at the US National Institutes of Health proposed the creation of a formal informatics infrastructure for EHR data. While operating within the current legal regulations and an ethical code of conduct, they describe the creation of a deceased subject integrated data repository as an effective tool for observational clinical research. Looking forward, it is with increasing interest and urgency that we build the necessary tools and maintain these guiding principles for the use of posthumous medical data. With the advancing technologies of both “big data” as well as digital healthcare reporting tools, it is imperative that we establish the foundation of this area of medical research so that we can advance the quality of research conducted while protecting the privacy and respect for those in our society.

References

- Krutzinna J., Taddeo M., Floridi L. (2019) An Ethical Code for Posthumous Medical Data Donation. In: Krutzinna J., Floridi L. (eds) The Ethics of Medical Data Donation. Philosophical Studies Series, vol 137. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04363-6_12

- Huser V, Cimino JJ. Don’t take your EHR to heaven, donate it to science: legal and research policies for EHR post mortem. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(1):8-12. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002061

- Health Information of Deceased Individuals, https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/guidance/health-information-of-deceased-individuals/index.html

- Use of Electronic Patient Data in Research, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/use-electronic-patient-data-research/2011-03

- Data donation after death, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4718407/

Images