Privacy and Anti-Trust by Todd Young

I have long been concerned about what mergers and acquisitions mean for privacy agreements. Beyond my concerns about the notice-and-consent framework[1], it seemed to me that a change of ownership of the firm, as in the case of a merger or acquisition, is particularly problematic for individual privacy. After all, people agree to share the personal information in a particular context, and a change of ownership of the firm can radically change that context.

I could think of particularly sensational hypothetical mergers to elicit lively discussion with friends and colleagues: What if Facebook bought 23andme and used the genetic information to map out families, and cancer-proneness? (Facebook has shown interest in medical information[2]. A recent study showed how large DNA database can be used to identify individuals.[3]) What if BlueCross signed an information sharing agreement with Ancestry? (Insurance companies are terrified of cheap DNA tests for consumers.[4]) Or what if Google bought FedEx and made business document shipping free but you had to agree to allow them to scan the documents as part of their effort to organize the world’s information? (OK, there’s no evidence I could find of this, but it’s basically the same deal you agree to with your Gmail account.)

How should we view such proposed mergers? How should we decide if such a merger was harmful to consumers? If such a merger was indeed likely to be harmful, who could we rely on to stop it from happening? The Federal Trade Commission? What monopoly would they be preventing? What pricing power would the new company have if its apps were free all along? Could it be considered a harm to accumulate too much personal information about people?

I will discuss each of these issues and then look at a real case from 2014, when Facebook purchased WhatsApp for $19B where examine the reactions to this merger in the EU and in the U.S. and offer my opinion on it.

Let’s start with legal framework of Antitrust, and its enforcers[5]. The FTC is a bipartisan federal agency with a unique dual mission to protect consumers and promote competition. The FTC enforces anti-trust laws and will challenge anti-competitive mergers.[6] Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits mergers that “may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.”[7] The process of evaluation is to: define the relevant market, test theories of harm, and examine efficiencies created by the merger.

Relevant Market

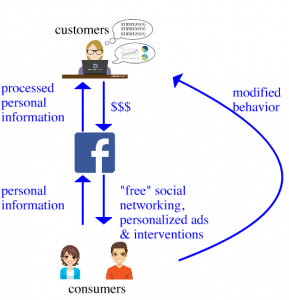

The FTC Horizontal Merger Guidelines[8], section 4, Market Definition specifies the line of commerce and the allows for the identification of the market participants, so market share can be considered. I propose to use Jaron Lanier’s characterization of the social media companies as ones that collect personal information about consumers for the purpose of selling to other firms (chiefly advertising) the promise of behavior modification of those same users.[9] The behavior modification could be to make a specific purchase of a product, or to “like” a particular tweet, or to read a certain news story, or even to attend a political rally.

To me, what is interesting about this market view is that it allows us to consider the actual harms that consumers are worried about[10], as well as the harms that typically get reviewed by the FTC – price and market power. Let’s take a deeper look at price.

Price, in an economic sense, is the factor that balances supply and demand. In a simpler way of thinking, price is what you give up for what you get, and Facebook users give up their personal information to use the platform ‘for free.’ According to Thomas Lenard, senior fellow and president emeritus at the Technology Policy Institute, “price is a proxy for a whole bunch of attributes.” In Jason Lanier’s description “Let us spy on you and in return you’ll get free services.” If Data is the new Oil, personal data is the jet fuel that powered Google, Amazon, and Facebook into the world’s most valuable companies top ten.[11] The price users pay is to allow Facebook to use their personal information.

In other words, the “price” consumers pay for social networking apps is the privacy of their personal information. Hence, we can look at the role of providing personal information as the “price” of social networking, and at the same time look at harms caused by the loss of privacy. This interpretation is not mine alone. Wired magazine’s June 2017 article “Digital Privacy is Making Antitrust Exciting Again” quotes Andreas Mundt, president of Germany’s antitrust agency, Bundeskartellant, saying he was “deeply concerned privacy is a competitive issue.”[12]

The FTC Horizontal Merger Guidelines clarify that non-price terms and conditions can also adversely affect consumers, and that non-price attributes can be considered as price. Further if the market is one of buyer power, the same analysis can be conducted for the ‘monopsony’ situation. So we can stay within the existing framework of the evaluation of mergers as being anti-competitive or not.

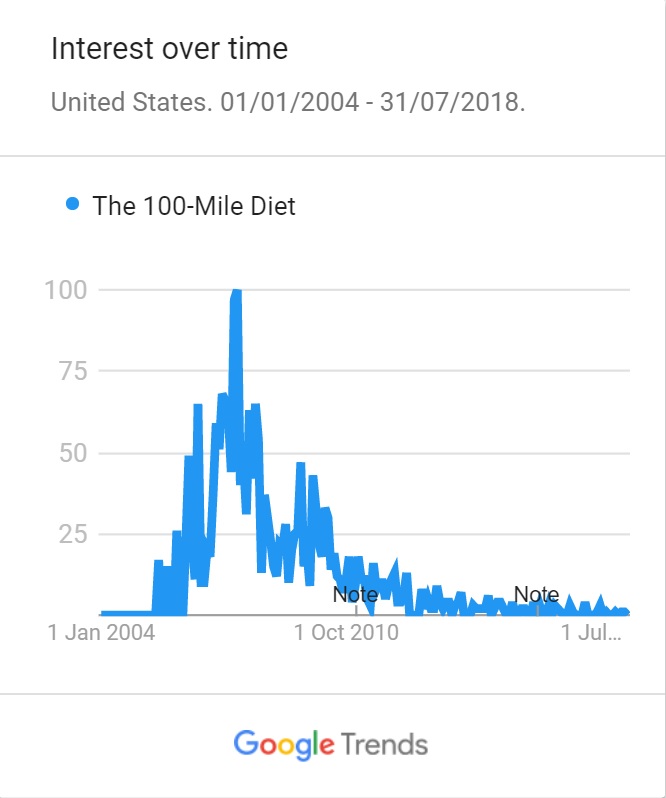

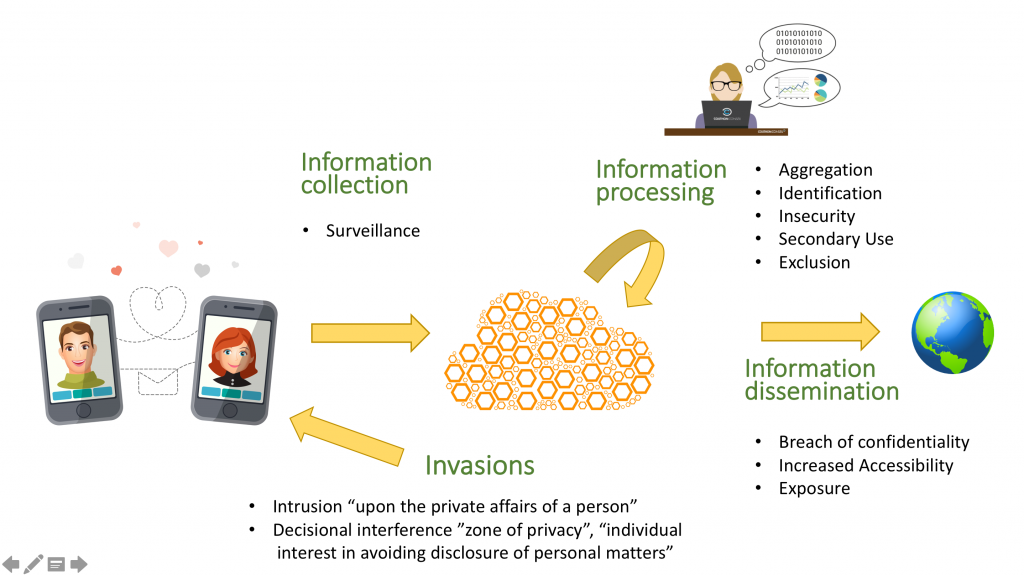

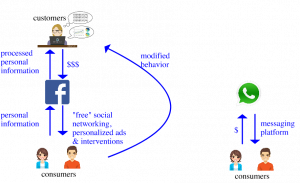

An anti-competitive merger would result in market power for the merged company, typically in terms of pricing power. However, as ‘price’ in this case contains the notion of private personal information, we can describe Facebook’s as in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Information and Money Flows for Facebook

The figure above illustrates that FaceBook is the purchaser of personal information from users, who, in exchange, get otherwise free services from FaceBook – a platform on which to build community and share (with that community, and with FaceBook). Facebook rents this information to its customers who sell ads or otherwise attempt to modify the user’s behavior based on a personalized environment.

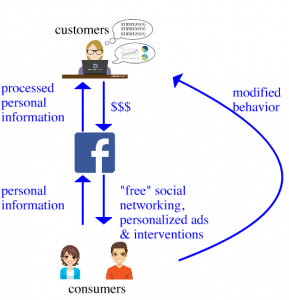

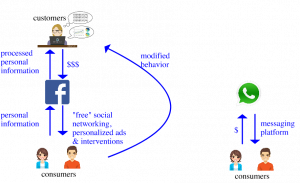

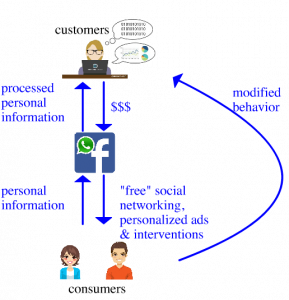

The determination of whether a merger of another company with FaceBook would be anti-competitive would thus include the effect of the price of service on other consumers. Or, in the economics of social media, how would the required information sharing change for customers of the old company change under the Facebook merger? Here are the pre-merger and post-merger information and money flows.

Figure 2. Pre-Merger Information and Money Flows for Facebook and WhatsApp

Figure 3. Post-Merger Information and Money Flows for Facebook and WhatsApp

I contend that through the merger, Facebook forced WhatsApp out of its hi-privacy, paid business model into a low-privacy “free” market, despite WhatsApp’s history of insisting on privacy for its customers. In the words of Tom Grossman, a senior branding consulting at Brand Union, from the Guardian, and quoted in Wired[13]:

“One of the reasons why so many millions have flocked to WhatsApp is the added level of privacy the brand provides. In a world where your every word echoes endlessly across the internet it was a communication channel where sharing could take place on a more contained level. However, much like Google’s acquisition of Nest and Facebook’s of Instagram, with this purchase consumers are suddenly associated with, and have their information accessible by a brand that they didn’t buy into. It’s this intrusion that can make it feel uncomfortable, as both you and your data are seized without your say-so.”

Theories of Harm

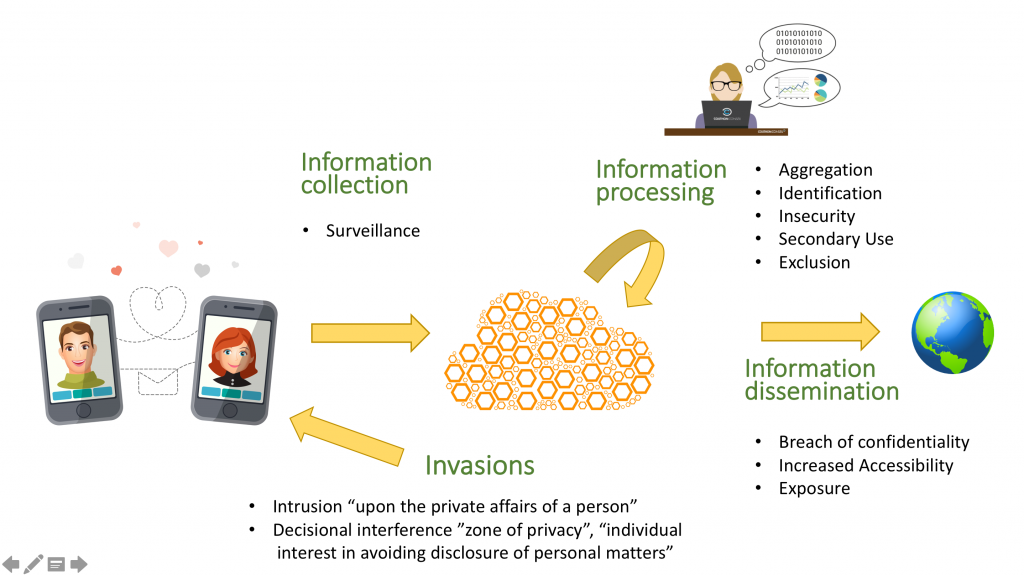

As I pointed out in the previous section, there was no financial harm to WhatsApp users, as their paid service became free in time, as it was integrated[14] into the Facebook family. As price includes a component of privacy, we need to look beyond monetary harm, and Daniel Solove’s Taxonomy of Privacy[15] is instructive in the evaluation of post-merger privacy harms. The Taxonomy describes the information flows and issues related to them.

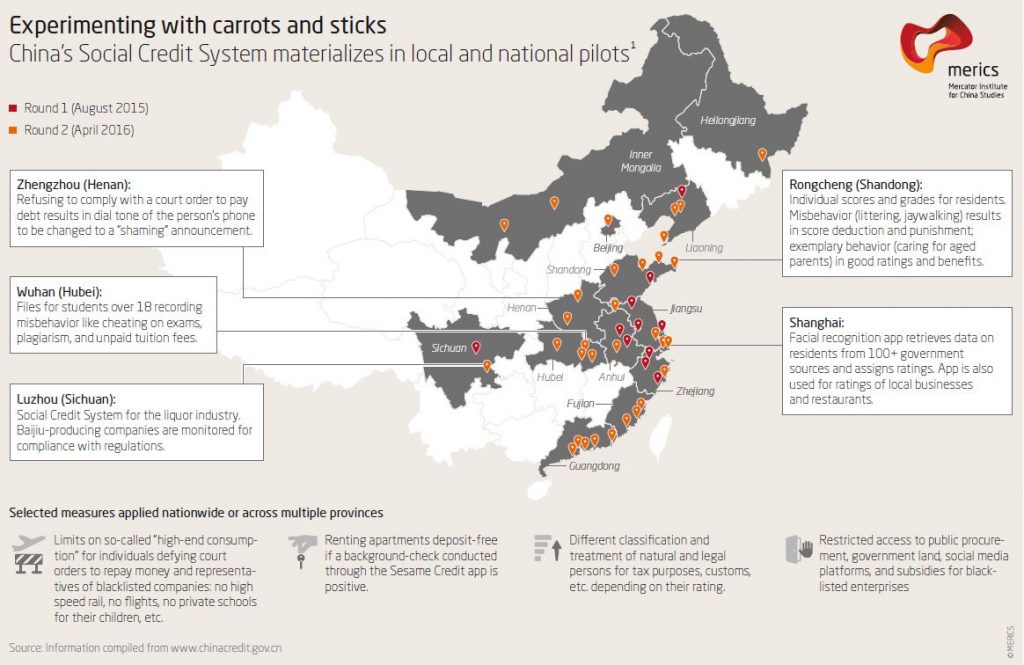

Figure 4. Solove’s Taxonomy of Privacy

In comparing the two apps and their business/privacy models, areas of significant difference include: 1) Surveillance – WhatsApp’s Koum said “Respect for your privacy is coded into our DNA… We don’t know your likes, what your search for on the internet or collect your GPS location…[16]” Facebook’s business is built around ‘likes’ and tracking your online. 2) Aggregation – the power of adding another layer of data, another network, into the Facebook graph must have been a key driver for the decision to acquire Whatsapp. 3) Secondary use – this is the crux of the outrage by WhatsApp users. They used the WhatsApp platform based on the user agreement, which showed a strong focus on privacy and security, and then all that data got sucked into the Facebook graph. 4) Breach of confidentiality – I could not reasonably include this as a harm had Facebook actually gotten the affirmative consent of WhatsApp users, but their insistence on defaulting the users into the agreement requires that I consider this to be a breach of confidentiality for the WhatsApp users. 5) Invasions of privacy. It’s hard not to include this as well given the way the WhatsApp consumer were assimilated into the Facebook graph.

Consumers are much more willing to share personal data with the promise of anonymization[17]. However, as personal information about individuals accumulates in the hands of large corporations, promises of anonymization of data becomes less viable, and consumers’ trust becomes misplaced. Narayanan and Shmatikov showed that they could successfully de-anonymize social network data based purely on topology.[18] Michael Zimmer similarly showed how difficult it is to anonymize Facebook data used in research. Despite researchers’ attempts to anonymize Facebook data for a college student population that was the subject of their research, the school and students were identified in a matter of days of the release of the study, putting the students’ privacy at risk.[19] Also recall the DNA study referenced on Page 1 (reference 3).

Real Harm and a Slap on the Wrist

The FTC did not block the merger but focused on WhatsApp’s privacy promises to its users: “We want to make clear that, regardless of the acquisition, WhatsApp must continue to honor these promises to consumers. Further, if the acquisition is completed and WhatsApp fails to honor these promises, both companies could be in violation of Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act and, potentially, the FTC’s order against Facebook,” the letter states.[20]

In 2014, Mark Zuckerburg was quoted as saying “We are absolutely not going to change plans around WhatApp and the way it uses user data. WhatsApp is going to operate completely autonomously.”[21] But, all that changed, and consumers were left with a choice to leave or stay and share their personal information. Even worse, despite the FTC’s admonition to “obtain consumers’ affirmative consent before doing so”, Facebook took the opposite approach and by default opted consumers in.

The FTC also used the Facebook/WhatsApp merger as a backdrop to provide guidance to other companies about keeping their pre-merger privacy promises post-merger.[22]

In the Facebook-WhatsApp merger, the EU and US both criticized and fined FaceBook, but the FTC did not prevent the merger. The fines ($112M by the EU and EU and US ultimately focused on keeping privacy promises), but were tiny compared with the $19B they paid for WhatsApp.

However, in the end, it was not theoretical harms that lead to the criticism and fines from the EU and the FTC. It was lies. Despite both companies being adamant about the security of WhatsApp consumer information, they went back on their promise. Apparently, the financial reward of merging the two data sets was just too much to resist, and the expected backlash, loss of customers, and fines was not enough to impact the final decision.

Efficiencies

The efficiency gained by Facebook was 1) the repurposing of private data from WhatsApp into their own social network ‘graph’, and 2) the elimination of a for paid-subscription-model/hi-privacy competitor from the social networking landscape. Both of these efficiencies hurt consumers to the benefit of Facebook.

Conclusion

Mergers and Acquisitions change the context of privacy for the user and can threaten

I think the FTC got it wrong – I think WhatsApp was a Maverick company per the FTC Horizontal Merger Guidelines document. From that document (emphasis mine): [my comments included like this]

2.1.5 Disruptive Role of a Merging Party The Agencies consider whether a merger may lessen competition by eliminating a “maverick” firm, i.e., a firm that plays a disruptive role in the market to the benefit of customers. For example, if one of the merging firms [Facebook] has a strong incumbency position and the other merging firm [WhatsApp] threatens to disrupt market conditions with a new technology or business model [high-privacy], their merger can involve the loss of actual or potential competition. Likewise, one of the merging firms may have the incentive to take the lead in price cutting or other competitive conduct or to resist increases in industry prices. A firm that may discipline prices [sharing of personal information] based on its ability and incentive to expand production rapidly [because of consumer interest in high-privacy apps] using available capacity also can be a maverick, as can a firm that has often resisted otherwise prevailing industry norms to cooperate on price setting or other terms of competition.

Their maverick-ness was providing consumers with a paid $1-per-year service with the promise of high privacy. Facebook’s merger forced them to adopt the no-privacy model, essentially a much higher price for using that platform. Users and critics wrote that WhatsApp had betrayed them, and I agree.

NOTES

[1] Notice-and-consent relies upon the informed consent of the user, who often acknowledges the agreement with a simple click. However, there are many well-documented reasons to believe that the consent is neither informed, nor undertaken with complete free will: 1) agreements are notoriously long documents, 2) agreements are seldom written in clear, accessible language, 3) they can be changed at will by company with notice, 4) the company often decides what “material” changes merit a notice, 5) the company essentially holds all the power in the relationship as switching costs for the consumer are very high given the utility-like status of many social networking apps.

[2] https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/05/facebook-building-8-explored-data-sharing-agreement-with-hospitals.html

[3] https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/06/19/350231

[4] https://www.fastcompany.com/3022224/why-23andme-terrifies-health-insurance-companies

[5] https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/competition-guidance/guide-antitrust-laws/enforcers

Both the FTC and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) Antitrust Division enforce the federal antitrust laws. In some respects, their authorities overlap, but in practice the two agencies complement each other. Over the years, the agencies have developed expertise in particular industries or markets. For example, the FTC devotes most of its resources to certain segments of the economy, including those where consumer spending is high: health care, pharmaceuticals, professional services, food, energy, and certain high-tech industries like computer technology and Internet services.

[6] https://www.ftc.gov/about-ftc/what-we-do

[7] https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/merger-review/100819hmg.pdf

[8] https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/merger-review/100819hmg.pdf

[9] Jaron Lanier, 2018, Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now.

[10] https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/personalisation-vs-privacy

[11] https://www.wired.com/2017/06/ntitrust-watchdogs-eye-big-techs-monopoly-data/

[12] https://www.wired.com/2017/06/ntitrust-watchdogs-eye-big-techs-monopoly-data/

[13] https://www.epic.org/privacy/internet/ftc/whatsapp/

[14] I think the verb assimilated is actually more apropos, especially because of the opt-in-by-default strategy of gained consent that earned them fines around the world.

[15] Solove. A Taxonomy of Privacy. https://www.law.upenn.edu/journals/lawreview/articles/volume154/issue3/Solove154U.Pa.L.Rev.477(2006).pdf

[16] https://www.epic.org/privacy/internet/ftc/whatsapp/

[17] https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/personalisation-vs-privacy

[18] De-Anonymizing Social Networks. Arvind Narayana and Vitaly Shmatikov. The University of Texas at Austin.

[19] http://www.sfu.ca/~palys/Zimmer-2010-EthicsOfResearchFromFacebook.pdf

[20] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2014/04/ftc-notifies-facebook-whatsapp-privacy-obligations-light-proposed

[21] https://www.epic.org/privacy/internet/ftc/whatsapp/

[22] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/business-blog/2015/03/mergers-privacy-promises