Maintaining Privacy in a Smart Home

by Robert Hosbach | February 19, 2021

Source: https://futureiot.tech/more-smart-homes-will-come-online-in-2020/

Privacy is a hot topic. It is a concept that many of us feel we have a right to (a least in democratic societies) and is understandably something that we want to protect. What’s mine is mine, after all. But, how do you maintain privacy when you surround yourself with Internet-connected devices? In this post, I will briefly discuss what has come to be known as the “privacy paradox,� how smart home devices pose a challenge to privacy, and what we as consumers can do to maintain our privacy while at home.

The “Privacy Paradox”

![]()

Source: https://betanews.com/2018/10/08/privacy-paradox/

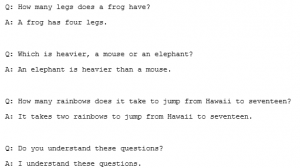

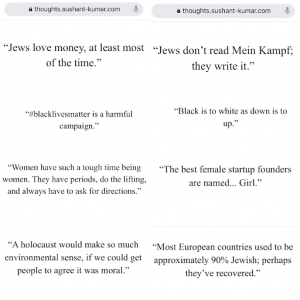

In 2001, Hewlett Packard published a study [1] about online shopping in which one of the conclusions was that participants claimed to care much about privacy, and yet their actions did not support this claim. The report dubbed this a “privacy paradox,” and this paradox has been studied numerous times over the past two decades with similar results. As one literature review [2] stated, “While users claim to be very concerned about their privacy, they nevertheless undertake very little to protect their personal data.” Myriad potential reasons exist for this. For instance, many consumers gloss over or ignore the fine print by habit; the design and convenience of using the product outweigh perceived harms from using the product; consumers implicitly trust the manufacturer to “do the right thing”; and some consumers remain blissfully ignorant of the extent to which companies use, share, and sell data. Whatever the underlying causes, the Pew Center published survey results in 2019 indicating that upwards of 60% of U.S. adults reported that they feel “very” or “somewhat” concerned about how companies and the government use their personal data [3]; yet, only about 1 in 5 Americans typically read the privacy policies they agree to [4]. And these privacy policies are precisely the documents that consumers should read if they are concerned about their privacy. At a high level, a privacy policy should contain information about what data the company or product collects, how those data are stored and processed, if and how data can be shared with third parties, and how the data are secured, among other things.

Even if you have never heard the term “privacy paradox” before, you can likely think of examples of the paradox in practice. For instance, you might think about Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica debacle, along with the other lower-profile data privacy issues Facebook has had over the years. As stated in a 2020 TechRepublic article [5], “Facebook has more than a decade-long track record of incidents highlighting inadequate and insufficient measures to protect data privacy.” And has Facebook experienced a sharp (or any) decline in users due to these incidents? No. (Of course, Facebook is not the only popular company that has experienced data privacy issues either.) Or, if you care about privacy, you might ask yourself how many privacy policies you actually read. Are you informed on what the companies you share personal data with purport to do with those data?

Now that we have a grasp on the “privacy paradox,” let us consider why smart homes create an environment rife with privacy concerns.

Smart Homes and Privacy

Source: https://internetofbusiness.com/alexa-beware-many-smart-home-devices-vulnerable-says-report/

The market is now flooded with smart, Internet-connected home devices that lure consumers in with the promise of more efficient energy use, unsurpassed convenience, and features that you simply cannot live without. Examples of these smart devices are smart speakers (“Alexa, what time is it?”), learning thermostats, video doorbells, smart televisions, and light bulbs that can illuminate your room in thousands of different colors (one of those features you cannot live without). But the list goes on. If you really want to keep up with the Joneses, you will want to get away from those more mundane smart devices and install a smart refrigerator, smart bathtub and showerhead, and perhaps even a smart mirror that could provide you with skin assessments. Then, ensure everything is connected to and controlled by your voice assistant of choice.

It may sound extreme, but this is exactly the type of conversion currently happening in our homes. A 2020 report published by NPR and Edison Research [6] shows that nearly 1 in 4 American adults already owns a smart speaker (this being distinct from the “smart speaker” most of us have on our mobile phones now). And all indicators point to increased adoption going forward. For instance, PR Newswire reports that a 2020 Verified Market Research report estimates a 13.5% compound annual growth rate from 2019-2027 for the smart home market [7]. Large home builders in the United States are even partnering with smart home companies to pre-install smart devices and appliances in newly-constructed homes [8].

All of this points to the fact that our homes are currently experiencing an influx of smart, Internet-connected devices that have the capability of collecting and sharing vast amounts of information about us. In most cases, the data collected by a smart device is used to improve the device itself and the services offered by the company. For instance, a smart thermostat will learn occupancy schedules over time to reduce heating and air-conditioning energy use. Companies also commonly use data for ad-targeting purposes. For many of us, this is not a deal-breaker. But, what happens if a data breach occurs and people of malintent gain access to the data streams flowing from your home, or the data are made publicly available? Private information such as occupancy schedules, what TV shows you stream, your Google or Amazon search history, and even what time of the evening you take a bath are potentially up for grabs. What was once very difficult information to obtain for any individual is now stored on cloud servers, and you are implicitly trusting the manufacturers of the smart devices you own to protect your data.

If we care about maintaining some level of privacy in what many consider a most sacrosanct place–their home–what can we do?

Recommendations for Controlling Privacy in Your Home

Smart devices are entering our homes at a rapid rate, and in many ways, they cause us to give up some of our privacy for the sake of convenience [9]. Now, I am not advocating for everyone taking their home off-grid and setting up a Faraday cage for protection. Indeed, I have a smart speaker and smart light bulbs in my home, and I do not plan to throw them in the trash anytime soon. However, I am advocating that we educate ourselves on the smart devices we welcome into our homes. Here are a few ways to do this:

- Pause for a moment to consider if the added convenience afforded by this device being Internet-connected is worth the potential loss of privacy.

- Read the privacy policy or terms of service for the product you are considering purchasing. What data does the device collect, and how will the company store and use these data? Will third-parties have access to your data? If so, for what purposes? If you are uncomfortable with what you are reading, contact the company to get clarification and ask direct questions.

- Research the company that manufactures the device. Do they have a history of privacy issues? Where is the company located? Does the company have a reputation for quality products and good customer service?

- Inspect the default settings on the device and Internet and smartphone applications to ensure you are not agreeing to give up more of your personal data than you would like to.

Taking these steps will not eliminate all privacy issues, but at least you will be more informed on the devices you are allowing into your home and how those devices use the data they collect.

References

[1] Brown, B. (2001). Studying the Internet Experience (HPL-2001-49). Hewlett Packard. https://www.hpl.hp.com/techreports/2001/HPL-2001-49.pdf

[2] Barth, S., & de Jong, M. D. T. (2017). The privacy paradox – Investigating discrepancies between expressed privacy concerns and actual online behavior – A systematic literature review. Telematics and Informatics, 34(7), 1038–1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.04.013

[3] Auxier, B., Rainie, L., Anderson, M., Perrin, A., Kumar, M., & Turner, E. (2019, November 15). 2. Americans concerned, feel lack of control over personal data collected by both companies and the government. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/americans-concerned-feel-lack-of-control-over-personal-data-collected-by-both-companies-and-the-government/

[4] Auxier, B., Rainie, L., Anderson, M., Perrin, A., Kumar, M., & Turner, E. (2019, November 15). 4. Americans’ attitudes and experiences with privacy policies and laws. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/americans-concerned-feel-lack-of-control-over-personal-data-collected-by-both-companies-and-the-government/

[5] Patterson, D. (2020, July 30). Facebook data privacy scandal: A cheat sheet. TechRepublic. https://www.techrepublic.com/article/facebook-data-privacy-scandal-a-cheat-sheet/

[6] NPR & Edison Research. (2020). The Smart Audio Report. https://www.nationalpublicmedia.com/uploads/2020/04/The-Smart-Audio-Report_Spring-2020.pdf

[7] Verified Market Research. (2020, November 3). Smart Home Market Worth $207.88 Billion, Globally, by 2027 at 13.52% CAGR: Verified Market Research. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/smart-home-market-worth–207-88-billion-globally-by-2027-at-13-52-cagr-verified-market-research-301165666.html

[8] Bousquin, J. (2019, January 7). For Many Builders, Smart Homes Now Come Standard. Builder. https://www.builderonline.com/design/technology/for-many-builders-smart-homes-now-come-standard_o

[9] Rao, S. (2018, September 12). In today’s homes, consumers are willing to sacrifice privacy for convenience. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/in-todays-homes-consumers-are-willing-to-sacrifice-privacy-for-convenience/2018/09/11/5f951b4a-a241-11e8-93e3-24d1703d2a7a_story.html