When is faking it alright?

by Randy Moran | March 5, 2021

Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash

The AI news has been littered with Deep Fake articles over the last couple of years. Some articles are about using it for fun (CNet), some are using it to demonstrate technical capability, like with recent Tom Cruise fakes (Piper). And, some are using it maliciously to harm or try to sway opinions and rally opposition (“Malicious use of deep fakes is a threat to democracy everywhere”). All of this points to the fact that AI is just technology, a tool to be used for either good or bad purposes.

The recent announcement of WE-FORGE (DARTMOUTH COLLEGE), takes faking in a whole different direction. WE-FORGE can generate fake, realistic documents, not for fun and not quite for malicious reasons, but to obfuscate actual content; for the purposes of counter espionage. This AI approach can be used to hide corporate or national security documents within the noise of numerous other fake documents. As their announcement points out, this noise aspect was used successfully in WWII to thwart efforts in discovering upcoming military maneuvers in Sicily.

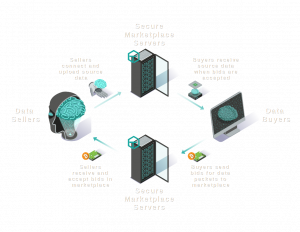

The above announcement leads to thinking about its application for obfuscating (hiding) individuals activity from tracking. As we have reviewed in the w231 course work, individuals’ have limited to no control over their data in today’s web, social, and application landscape. We have seen that privacy policies, for the most part, serve and cover a firm more so than the individual. True protective legislation is years away; and will still be guided by procedure over individual rights and likely to be fought hard from highly profitable tech firms. The procedures to control your own information are laborious and don’t completely provide the controls one would want. The only choices are to live with it so you can utilize the service or stop using the service altogether, limiting one’s ability to connect and participate in the good aspects of the technology.

Helen Nissenbaum, whose privacy framework outlined week 5 in “A Contextual Approach to Privacy Online” (Nissenbaum 32-48) was a co-author, along with Finn Brunton, of a book called “Obfuscation: A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protest” (Brunton and Nissenbaum). In that book, they outline obfuscation as “the deliberate addition of ambiguous, confusing, or misleading

information to interfere with surveillance and data collection.” They outline numerous variations for obfuscating your identity; chafing, location spoofing, disinformation, etc. As they state, in chapter three, “privacy is a multi-faceted concept, and a wide range of structures, mechanisms, rules, and practices are available to produce it and defend it.” There are legal mechanisms, there are technical solutions, and there are application options. To these, their goal in that chapter, they feel the need for an individual to utilise obfuscation; to produce noise that looks like normal activity so as to hide the actual activity. It provides an individual way to camouflage activity when other aspects fail. It is similar to the WE_FORGE process above, but for individuals.

To enable that strategy, Helen partnered with Daniel Howe and Vincent Toubiana, to develop a tool called “TrackMeNot” (Howe et al.) that puts these ideas to practice. It provides a browser plugin for Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox, an option so that your activity can be obfuscated. It generates random search queries through several search services (Google, Bing, Yahoo,etc.) to hide an individuals’ actual search history. One could spend the time to do it manually, but the systematic approach is much more efficient.

While legislation may come in time, and individuals may gain control of their data eventually, they can now hide their activity. This is not necessarily going to be sought out by everyone. It will likely only be used by those aware of the lengths organizations and companies have gone through to identify and categorize users. As the authors put it, “it’s a small revolution” for those interested in mitigating and defeating surveillance. To a common individual, it’s an effort they don’t care to spend. To the few aware individuals, it’s one small step towards gaining back control of one’s own privacy. The browser plugins provide obfuscation for at least this one specific aspect of user activity.

Still, I can see additional applications being developed in the future, in social networking apps and other service areas, utilizing AI to generate noise that the application AI mechanisms are trying to capture and identify. Just as hackers use AI to infiltrate networks (F5), AI is now being used by software (IBM) to identify and counter those attacks. Most folks know AI/ML is being

used to catalog and categorize individuals and their activity; the next obvious step is to use the technology to thwart that activity for those that are concerned. To some, including the companies capturing the data, it may seem wrong to pollute the data. Still, it is justified and warranted to those individuals who care about their privacy since laws have not caught up to stop the proverbial data peeping-toms. In the latter case, they just have to look at more

information, which is no different from what WE-FORGE is trying to accomplish with its counter-espionage tactics.

Bibliography

- Brunton, Finn, and Helen Nissenbaum. Obfuscation: A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protect. The MIT Press, 2015.

- CNet. “26 Deep fakes that will freak you out.” CNet Pictures, 15 Jan 2020,

https://www.cnet.com/pictures/26-deepfakes-that-will-freak-you-out/. - DARTMOUTH COLLEGE. “Cybersecurity researchers build a better ‘canary trap.’” EurekAlert, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1 Mar 2021, https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2021-03/dc-crb022621.php.

- F5. “AI-powered Cyber Attacks.” 2020, https://www.f5.com/labs/articles/cisotociso/ai-powered-cyber-attacks.Howe, et al. “TrackMeNot.” Trackmenot.io, 2016, http://trackmenot.io/.

- IBM. “IBM Security.” Artificial intelligence for a smarter kind of cybersecurity, 2021, https://www.ibm.com/security/artificial-intelligence.

- “Malicious use of deepfakes is a threat to democracy everywhere.” The Startup, 2019, https://medium.com/swlh/malicious-use-of-deepfakes-is-a-threat-to-democracy-everywhere-51a020bd81e.

- Nissenbaum, Helen. “A Contextual Approach to Privacy Online.” Daedalus, vol. Fall, no. 2011, 2011, pp. 32-48, https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/daedalus/downloads/Fa2011_Protecting-the-Internet-as-Public-Commons.pdf.

- Piper, Daniel. Creative Boq, 1 Mar 2021,

https://www.creativebloq.com/news/tom-cruise-deepfakes