The Looming Revolution of Online Advertising

By Anonymous, October 30, 2020

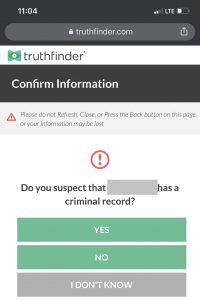

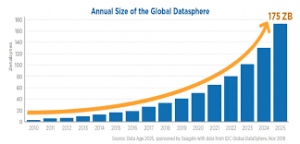

In the era of the internet, advertising is getting creepily accurate and powerful. Large ad networks like Google, Facebook, and more collect huge amounts of data, through which they can infer a wide range of user characteristics, from basic demographics like age, gender, education, and parental status to broader interest categories like purchasing plan, lifestyle, beliefs, and personality. With such powerful ad networks out there, users often feel like they are being spied on and chased around by ads.

Image credit: privateinternetaccess.com

How is this possible?

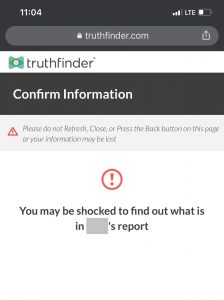

How did we leak so much data to these companies? The answer is through cross-site and app tracking. When you surf the internet, going from one page to another, trackers collect data on where you have been and what you do. According to one Wall Street Journal study, the top fifty Internet sites, from CNN to Yahoo to MSN, install an average of 64 trackers[1]. The tracking can be done by scripts, cookies, widgets, or invisible image pixels embedded on the sites you visit. You probably have seen the following social media sharing buttons. Those buttons, no matter you click them or not, can record your visits and send data back to the social platform.

Image credit: pcdn.co

A similar story is happening on mobile apps. App developers often link in SDKs from other companies, through which they can gain analytic insights or show ads. As you can imagine, those SDKs will also report data back to the companies and track your activities across apps.

Why is it problematic?

Cross-site or app tracking poses great privacy concerns. Firstly, the whole tracking process happens behind the scenes. Most users are not aware of it until they see some creepily accurate ads, and even if they are aware of it, the users often have no idea how the data is collected and used, and who owns it. Secondly, only very technically sophisticated people know how to prevent this tracking, which can involve tedious configuration or even installation of other software. To make things worse, even if we can prevent future tracking, there is no clue how to wipe out the already collected data.

In general, cross-site and app activities are collected, sold, and monetized in various ways with very limited user transparency and control. GDPR and CCPA have significantly improved this. Big trackers like Google, Facebook, and more provide dedicated ad setting pages (1, 2), which allow users to delete or correct their data, to choose how they want to be tracked, etc. Though GDPR and CCPA gave users more control, most users stay with the default options and cross-site tracking remains prevalent.

The looming revolution

With growing concerns of user privacy, Apple took a radical action to kill the cross-site and app tracking. Over the past couple of years, Apple gradually rolled out the feature of Safari Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP)[2], which curtailed companies’ ability to install third-party cookies. With Apple taking the lead, Firefox and Chrome browsers are also launching similar features as ITP. In the release of IOS 14, Apple brought a similar feature as ITP to Apps world.

Image credit: clearcode.com

While at the first glance this may sound like a long-overdue change to safeguard users’ privacy, when delving deeper, it could create backlashes. Firstly, internet companies collect data in exchange for their free services: products like Gmail, Maps, Facebook are all free of use. According to one study from VOX, in an ad-free internet, the user would need to pay $35 every month to compensate for ad revenue[3]. Some publishers even threatened to proactively stop working on Apple devices. Secondly, Apple’s ITP solution doesn’t give much chance for users to participate. Cross-site tracking can in general enable more personalized services, more accurate search results, better recommendations, etc. Some uses may choose to opt-in to allow cross-site tracking for this purpose. Thirdly, Apple’s ITP only disabled third party cookies, and there are many other ways to continue the tracking. For example, ad platforms can switch to device-id or “fingerprint” the users by combining IP address and Geolocation.

Other radical solutions were also proposed, such as Andrew Yang’s Data Dividend Project. With many ethical concerns and the whole ads industry at stake, it is very interesting to see how things play out and what other alternatives are proposed around cross-site and app tracking.

References