All about Grandma

By Anonymous, October 23, 2020

My grandma Diane lives in Tulsa, OK on a small farm with one of my aunts, Heather, my uncle Carl, my two cousins Carl III and Toby, and my uncle Carl’s mom Bethanne. They raise goats and fowl, have a couple house dogs and some cats that come and go as they are wont to. The farm has a pond that the dogs swim in sometimes. These are things that I know because they’re my family. I’ve spent countless Thanksgivings and Christmases and been to several weddings with them.

What I didn’t know until today was that grandma is a registered Republican and Heather and Carl are registered Democrats. I didn’t intend to find this information. Rather with the 2020 election on the mind and news media covering early voting, I decided to do a cursory search about what voting information exists in the public domain. It took less than a minute to stumble onto grandma’s voter registration on the data aggregator: voterrecords.com, where voter registration records are available in searchable form for 16 states, Oklahoma included.

Of course, voter registration records have been public for a long time, but before sites like voterrecords.com it took real effort to go peruse voter rolls. While the process differed from state to state, you typically had to go to the local county office or the secretary of state’s office to formally request access. These barriers meant only the most interested of actors, like political parties or investigative journalists, took the time to do it. Now, this information is available almost accidentally to anyone with an internet connection anywhere in the world.

While presence of the internet makes access to voter records fundamentally different than in the past, what makes it concerning now is the degree to which political affiliation has become enmeshed with personal identity, particularly for more extreme actors on both ends of the political spectrum, some of which threaten violence.

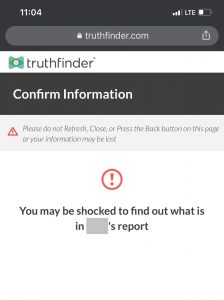

To make matters much worse, voterrecords.com connects voter registration information to sites that conduct extensive background searches – truthfinder.com and beenverified.com – all without transparent labeling that prominently displayed buttons will trigger a background search.

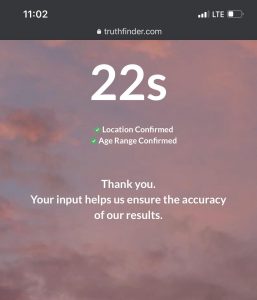

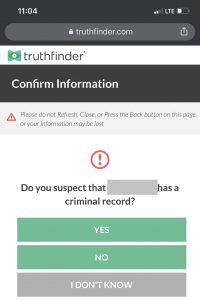

Truthfinder conducts a search of property records, criminal records, bankruptcy records, social media accounts, etc. While truthfinder exploits public records databases for much of this information, its site is set up to make use of users’ interactions to reinforce algorithmic conclusions about which records are related to the actual person in question. Presenting follow-on questions in a way that most users are likely to think that the site is trying to isolate a particular individuals’ records, the questions ask users to confirm or deny algorithmically generated relationships with other records it has come across, thereby strengthening the person-matching algorithms that form the core of those sites.

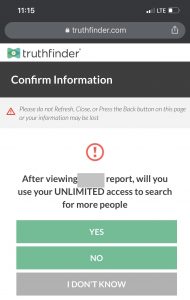

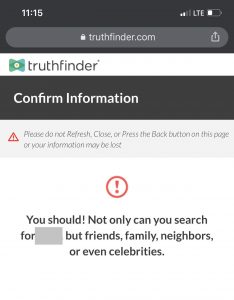

After asking several such questions the site prompts users to search for more people – including people with which the person likely has no personal connection such as ‘celebrities’. Truthfinder’s charges for its services, and its model invites people to conduct ‘unlimited’ searches over a month, rather than purchase individual reports. Furthermore, the generated report contains information not just about the person you’ve gone down a rabbit hole searching for but also about several people that truthfinder has determined are related to the person you’ve searched for.

It is through this that I learned, despite having known grandma all my life, that a lien was put on the farm last year, that she received her social security number and card around the time she turned 18 rather than at birth, and the VIN number on her Toyota Sequoia. While she doesn’t have a criminal record, several people in neighboring states with similar names do. While I know those people aren’t her, someone who doesn’t know her as well may not and might mistakenly come to the conclusion that my grandma has a problem with shoplifting. Truthfinder’s presentation of this information makes this outcome more likely by exaggerating and not disclaiming that the information may not be linked to the right person, as happened in this case. This is all in addition to a litany of phone numbers, email addresses, social media accounts, amazon wish lists, and the addresses she has lived at or co-signed for going back decades. A couple more clicks yields similar information about all of my Oklahoma relatives over the age of 18.

While voter registration records and for that matter each of the other sets of public records used by these sites historically may have had valid reasons for being in the public domain, the internet has enabled aggregation across these datasets in a way that it literally takes less than 10 minutes to stumble unintentionally from a person’s voter record to knowing some of the most personal aspects of their lives like bankruptcy and criminal records, and not much longer to unearth similar information about nearly everyone they are related to.

This is made all the more troubling by the devolution in public discourse and increase in othering as personal identities of all sorts and stripes are increasingly coalescing into constellations around bipolar political affiliations. This is all paired with increasing rhetoric of political violence. Americans should consider carefully what information is put into the public domain, and should advocate to their state legislatures to curtail the publication and aggregation of such data sources.