Uber can take you somewhere, could it also take advantage of your personal information?

By Yuze Chen | March 7, 2020

Nowadays, people are using technology to help them get around the city. Ride-sharing platforms such as Uber and Lyft are being used by hundreds and thousands of people around the world to help them get from point A to point B. These platforms help the riders with a lower-than-taxi fare, removes the hassle to book an appointment with taxi companies in advance. They also give drivers an opportunity to earn extra income using their own vehicles. With the convenience to take people around the city on their fingertips, ride-sharing companies are also known for their sketchy privacy policy.

Photo by Austin Distel on Unsplash

What Data does Uber Collects

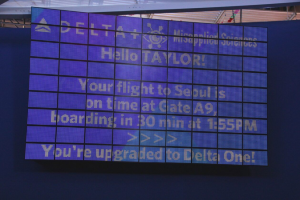

According to Uber’s Privacy Notice, Uber collects a variety of data including three main aspects: Data provided by user, such as username, email, address, etc; Data created when using Uber services, such as user’s location, app usage and device data; Data from other sources, such as Uber partners who provide data to Uber. Overall, the personal identifiable information (PII) are collected and stored by Uber. Besides that, Uber also collects and stores information that can reconstruct an individual’s daily life, such as location history. With the wealth of PIIs collected and stored by Uber, the user should be concerned about what Uber can do with the data.

Photo by Charles Deluvio on Unsplash Solove’s Taxonomy Analysis

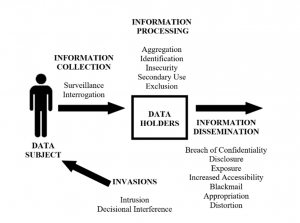

Solove’s Taxonomy provides us a framework to analyze the potential harm on the data subject (the user). According to Solove’s Taxonomy, Uber users are the data subject. When the user uses the Uber service, their personal data are transmitted to Data Holder, which is Uber. Then it will go through Information Processing step in Solove’s Taxonomy, including aggregation, identification, etc. After processing the data, there will be a Information Dissemination step where Uber can take action on user’s data.

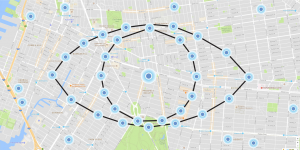

Information Collection

Let’s look at the first step in Solove’s Taxonomy – Information Collection. As discussed above, Uber collects data in three ways. However, there is a weird clause in Uber’s privacy notice III. A. 2. Location data section: “precise or approximate location data from a user’s mobile device if enabled by the user… when the Uber app is running in the foreground (app open and on-screen) or background (app open but not on-screen) of their mobile device”. This means Uber is able to always collect the user’s current location on background even though the user isn’t using the app. The clause gives Uber an opportunity to always monitor the user’s location after using Uber once. This creates potential harm to the user because it’s possible that a user’s location is always being collected by Uber without consent.

Information Processing

In the Information Processing step of Solove’s Taxonomy, Uber has a couple of sketchy terms in their privacy policy. In III. A. 2 Transaction Information, Uber claims that if a user refers a new user with the promo code, both user’s information will be associated in Uber’s database. This practice could be harmful to both user’s privacy and could cause some unpredicted consequences. For example, many users simply post their promotion code to a public blog or discussion board. Without knowing the referee who could use the promotion code, there is potential privacy and legal harm to to associate two strangers. For example, if the referee were under investigation of a crime when using Uber, the referer user could have also been involved in the legal matter, even if they don’t know each other.

Information Dissemination

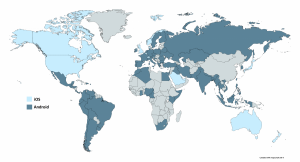

According to Privacy Policy Section III. D, Uber could share the user data with third parties such as Uber’s data analytics providers, insurance and financing partners. It does not specify who those partners are and how they are able to do with the data. It is obvious there will be potential harms to the user during this step. First, the user might not want their data to be disclosed to the third party other than Uber. This is more privacy concerns

Conclusion

According to our analysis on Uber’s privacy policy, we found plenty of surprising terms that would jeopardize user’s privacy. The data collection, data processing, and data dissemination are all having issues with user consent and user privacy protection. Some are even pulling users into potential legal issues. The wording of the Privacy Notice makes it easy for Uber to take advantage of user data legally, such as selling to its partner. There are a lot that Uber could do to better address those privacy issues in the Privacy Notice.

References

https://www.uber.com/global/en/privacy/notice/

https://wiki.openrightsgroup.org/wiki/A_Taxonomy_of_Privacy