Online Privacy in a Global App Market

By Julia H. | March 9, 2022

The United States’ west coast is home to thousands of technology companies trying to innovate, find a niche and make it big. Inevitably, much of the products developed here reflects it’s western roots and doesn’t adequately consider the risks to its most vulnerable users which may be thousands of miles away. This was the case with Grindr, which prides itself on being the world’s largest social networking app for gay, bi, trans, and queer people. Instead of being a safe space for a marginalized community, a series of security failures combined with not enough emphasis on user privacy has put some LGBTQ+ communities around the world at serious risk over the past decade. Grindr has thankfully responded by making updates that focus on the safety of its users. Still, much can be learned from the ways the platform was abused and how different implementation decisions can be made in order to protect users, especially in high stakes situations.

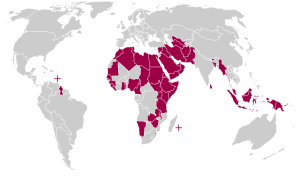

Human Dignity Trust, Map of Countries that Criminalise LGBT People, 2022

Today, “71 jurisdictions criminalise private, consensual, same-sex sexual activity” [1]. Even in places where it isn’t a criminal offience, individuals can find themselves facing harassment and other hate crimes due to their gender or sexual orientation. In Egypt, for example, police have been known to entrap gay men by detecting their location on apps like Grind and using the existence of the app itself, as well as screenshots and messages from the app, as part of debauchery case [2]. This has been a particularly prevalent problem since 2014 when Grindr security issues, especially surrounding easy access to user location by non-app users, were first brought to light by cybersecurity firm Synack [3]. Grindr’s first response was to note that location sharing can be disabled and to go ahead and disable the feature by default in well known homophobic countries such as Russia, Nigeria, Egypt, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. Despite this, triangulating the location of a user was still possible due to the order in which profiles appear in the app [4].

@Seppevdpll, Trilateration via Grindr, 2018

Sharing exact user location with 3rd parties, or enough information to triangulate an individual, violates privacy laws such as GDPR and California’s CCPA regulation. A huge miss for Grindr outside of how this information could be abused by conservative governments. In parts of California, where Grindr is based, there is a large, vibrant and welcoming gay community. There is a certain level of anonymity in numbers that can be lost elsewhere. Thus, maintaining the safe online space the app was likely meant to be is not just about implementing technical security practices and adhering to legislation. It means taking into account the cultural differences among app users when designing interactions.

Grindr has faced much scrutiny and backlash and has luckily reacted with some updates to its application. They have launched kindr, a campaign to promote “diversity, inclusion, and users who treat each other with respect” [5] that included an update to their Community Guidelines. They have also introduced the ability for users to unsend messages, set an expiration time on the photos they send, and block screenshots [6]. These features, in combination with the use of VPNs, have made it easier for members of the LGBTQ+ community to protect themselves while using Grindr.

Kindr Grindr, 2018

Having a security and privacy-first policy when developing apps should be the standard. Companies all over the world should take on the responsibility of protecting their users with the decisions that are made during design and implementation. Moreover, given the global audience that most companies are targeting these days, they should strive to consider the implications of the technology being released in settings different to those of its developer. Particularly by including input during the development process from different types of users.

Citations

[1] “Map of Countries That Criminalise LGBT People.” Human Dignity Trust, https://www.humandignitytrust.org/lgbt-the-law/map-of-criminalisation.

[2] Brandom, Russell. “Designing for the Crackdown.” The Verge, The Verge, 25 Apr. 2018, https://www.theverge.com/2018/4/25/17279270/lgbtq-dating-apps-egypt-illegal-human-rights.

[3] “Grindr Security Flaw Exposes Users’ Location Data.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 28 Mar. 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/security-flaws-gay-dating-app-grindr-expose-users-location-data-n858446.

[4] @seppevdpll. “It Is Still Possible to Obtain the Exact Location of Millions of Men on Grindr.” Queer Europe, https://www.queereurope.com/it-is-still-possible-to-obtain-the-exact-location-of-cruising-men-on-grindr/.

[5] “Kindr Grindr.” Kindr, Grindr, 2018, https://www.kindr.grindr.com/.

[6] King, John Paul. “Grindr Rolls out New Features for Countries Where LGBTQ Identity Puts Users at Risk.” Washington Blade: LGBTQ News, Politics, LGBTQ Rights, Gay News, 13 Dec. 2019, https://www.washingtonblade.com/2019/12/13/grindr-rolls-out-new-features-for-countries-where-lgbtq-identity-puts-users-at-risk/.

Singer, Natasha, and Aaron Krolik. “Grindr and OkCupid Spread Personal Details, Study Says.” New York Times, New York Times, 13 Jan. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/13/technology/grindr-apps-dating-data-tracking.html.

The Digital Rights of LGBTQ+ People: When Technology Reinforces Societal Oppressions.” European Digital Rights (EDRi), 15 Sept. 2020, https://edri.org/our-work/the-digital-rights-lgbtq-technology-reinforces-societal-oppressions.