Your phone is following you around.

By Theresa Kuruvilla | March 9, 2022

We live in a technologically advanced world where smartphones have become an essential part of our daily lives. Most individuals start their day with a smartphone wake-up alarm, scrolling through daily messages and news items, checking traffic conditions, work emails, calling family, or watching a movie or sports; the smartphone has become a one-stop-shop for everything. However, many people are unaware of what happens behind the screens.

From the time you put the sim card on the phone, regardless of whether it is an android or iPhone, the phone IMEA, hardware serial number, SIM serial number, and IMSI and headphone number will be sent to Apple or Google. The telemetry applications of these companies work on accessing the mac addresses of nearby devices to capture the phone’s GPS location. Many people think turning off GPS location on the phone prevents them from being tracked. They are mistaken. These companies capture your every movement thanks to cell phone technology advancement.

Under law listening to someone else’s phone call without a court order is a federal crime. But no rules prevent private companies from capturing citizens’ precise movements and selling the information for a price. This shows the dichotomy between the legacy methods of privacy invasion and the lack of regulation around the intrusive modern technologies.

On January 6, 2021, a group of Trump supporters’ political rallies turned into a riot at the US Capitol. The event’s digital detritus has been the key to identifying the riot participants: location data, geotagged photos, facial recognition, surveillance cameras, and crowdsourcing. That day, the data collected included location pings for thousands of smartphones, revealing around 130 devices inside the Capitol, exactly when Trump supporters stormed the building. There were no names or phone numbers; however, with the proper use of the technology available, many devices were connected to their owners, tying anonymous locations back to names, home addresses, social networks, and phone numbers of people in attendance. The disconcerting fact is that the technology to gather this data is available for anyone to purchase at an affordable price. Third parties use readily available technology to collect these data. Most consumers whose name is on the list are unaware of their data collected, and it is insecure and vulnerable to law enforcement and bad actors who might use it to inflict harm on innocent people.

(Image: Location pings from January 6, 2021, rally)

Government Tracking Of Capital Mob Riot

For law enforcement to use this data, they must go through courts, warrants, and subpoenas. The data in this example is a bird’s-eye view of an event. But the hidden story behind this is how the new digital era and the various tacit agreements we agree on invade our privacy.

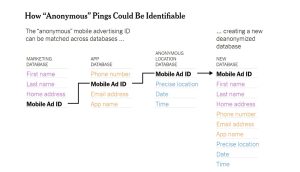

When it comes to law enforcement, this data is primary evidence. On the other hand, these IDs tied to smartphones allow companies to track people across the internet and on their apps. Even though these data are supposed to be anonymous, several tools allow anyone to match the IDs with other databases.

Below example from the New York times shows way to identify anonymous ping.

(Image: Graphical user interface, application)

Description automatically generated

While some Americans might cheer using location databases to identify Trump supporters. But they are ignorant that these commercial databases invade thier user privacy as well. The demand for location data grows daily, and deanonymization has become simpler. While smartphone technology might argue that they provide options to minimize tracking, it is only an illusion of control for individual privacy. The location data is not the only aspect; the tech companies capture every activity with all the smart devices deployed around you with the purpose of making your lives better. With the Belmont Principle of Beneficence, we must maximize the advantage of technology while minimizing the risk. In case of this, even though consumers receive many benefits such as better traffic maps, safer cars, and good recommendations, surreptitiously gathering this data and storing it forever and selling this information to the highest price bidder puts privacy at risk. The privacy acts such as GDPR and CCPR are in place to protect consumer privacy, but this doesn’t protect all people in the same manner. People should have the right to know how their data has been gathered and used. They should be given the freedom to choose a life without surveillance.

References:

Thompson, Stuart A. and Warzel, Charlie (2021, February 6). They stormed the capitol. Their apps tracked them. Medium. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/05/opinion/capitol-attack-cellphone-data.html

Thompson, Stuart A. and Warzel, Charlie (2019, December 21). How Your Phone Betrays Democracy. Medium. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/21/opinion/location-data-democracy-protests.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article

The editorial board New York Times (2019, December 21). Total surveillance is not what America signed up for. Medium. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/21/opinion/location-data-privacy-rights.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article

Nissenbaum, Helen F. (2011). A contextual approach to privacy online. Daedalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

Solove, Daniel J. (2006). A Taxonomy of Privacy. University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 154:3 (January 2006), p. 477. Medium. https://ssrn.com/abstract=667622

The Belmont Report (1979).Medium. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/the-belmont-report-508c_FINAL.pdf