How young is too young for social media ?

By Mariam Germanyan | July 9, 2021

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA)

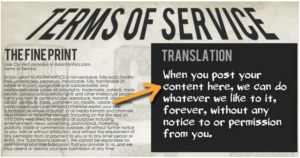

Time traveling back to 1998, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) surveyed about 200 websites with user profiles and discovered that 89 percent of them collect personal data and information from children aka minors. Based on those children, 46 percent of those websites did not disclose that such personal data was being collected or what the collected data was being used for. Ultimately not complying with Solove’s Taxonomy in explaining data collection, data usage, and data storage. The survey results aided Congress in developing the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998, 15 U.S.C. 6501–6505 requiring the FTC to issue and enforce regulations concerning children’s online privacy leading to a law that limits/restricts the online collection of data and information from children under the age of 13. Applying the protection only to children under 13, recognizing that younger children are considered more vulnerable to overreaching by marketers and may not understand the safety and privacy issues created by the online collection of personal information.

Consider Your First Social Media Account

Taking that into consideration, I ask you to think and reflect on the following questions listed below:

* How old were you when you created your first social media account?

* Why did you feel it was necessary to make an account in the first place?

* Did you lie about your age in order to register for an account?

* If so, why did you do it?

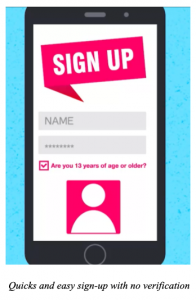

* How easy was it to make the account?

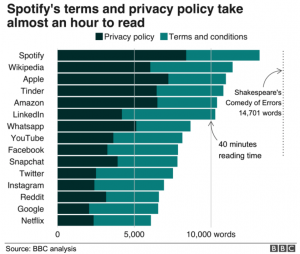

* Were you aware of the Privacy Policy associated with the account?

* Did you read it?

* Looking back from an older age, was it worth it?

Advantages and Disadvantages of Social Media at an Early Age

Now let’s consider the advantages and disadvantages of starting social media at an early age. The advantages of starting social media at a young age include but not limited to allowing such users a place to converse and connect with others within their community which is known to make individuals feel better about themselves by growing more confident. A major advantage would be to help start activism in individuals at an early age where they can find support and either join or start their own communities where they fit in. On the other hand, the disadvantages include that at the age of 13, the prefrontal cortex is barely halfway developed putting such young users at a risky age and in a vulnerable phase because they are not aware of what is possible as they experiment more and encounter risky opportunities. In addition, the majority of children are not aware of data privacy, can risk their safety as they can potentially be exposed to strangers, cyberbullies, content they should not see, and potentially develop mental issues as social media can take a toll on mental health on appearance and expectations at an early age. As they advance through their years as a teenager, they become more aware of such risks and consequences of online behavior. On a final note, we should also consider the amount of productive time that children waste on such social media accounts.

After reading this blog post and knowing what you know now, I ask you to consider what age you consider old enough for social media.

References

Children Under 13 Should Not Be Allowed on Social Media, and Here is Why. (2020,

September 3). BrightSide  Inspiration. Creativity. Wonder.

https://brightside.me/inspiration-family-and-kids/children-under-13-should-not-be-allowed-on-social-media-and-heres-why-798768/

Complying with COPPA: Frequently Asked Questions. (2021, January 15). Federal Trade

Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/complying- coppa-frequently-asked-questions-0

When is the Right Age to Start Social Media? (2020, August 14). Common Sense Education.

https://www.commonsense.org/education/videos/when-is-the-right-age-to-start-social-media