Do you like it? Or do you like it?

By Anonymous | July 9, 2021

Imagine physics governed by positive, but not negative; computer science described with one, but not zero; the human brain functioning with excitation, but not inhibition; a debate with pro, but not con; logic constructed with true, but not false. Indeed this is an impossible world, for if the aforementioned had such imbalanced representations, none of them could exist. The problem is that despite this self-evident conclusion, many ubiquitous systems in our data driven world are intentionally designed to represent information asymmetrically in order to extract some form of value from its misrepresentation.

When information systems are created, the representation of the information that is relevant to the system is intentionally defined through its design. Furthermore the design of this representation determines the ways users can interact with the information it represents, and the motives that underlie these intentional decisions are often shaped by social, economic, technical, and political dynamics. The objective of this discussion is to consider the value of misrepresentation, the design of misrepresentation, and the ethical implications this has for individuals. For the sake of brevity, the intentional design of a single feature within Facebook’s user interface, will serve as the archetype of this analysis.

Consider for a moment that the Facebook “Like” button exists without a counterpart. There is no “Dislike” button and no equivalent symbolic way to represent an antithetical position to the self-declared proponents of the information whom had the ability to express their position with a “Like”. Now consider that approximately 34.53% of Earth’s human population is exposed to the information that flows through Facebook’s network every month (monthly active users). Given the sheer scale of this system, it seems logical to expect the information on this network to have the representational capacity to express the many dimensions that information often comes in. However, this is not the world we live in, and Facebook’s decision to design and implement a system-wide unary representation of data was a business decision, not a humanitarian one.

Value. In recent fMRI experiments it has been shown that there is a positive correlation between the number of “Likes” seen by a user and neural activity in regions of the brain that control attention, imitation, social cognition, and reward processing. The general exploitation of these neural mechanisms by advertisers is what forms the foundation of what is known today as the Attention Economy. In the Attention Economy what is valuable to the business entities that comprise this economy is the user’s attention. Analogously, just as coal can be transformed into electrical energy, a user’s attention can be transformed into monetary gains. Therefore, if harvesting more user attention equates to greater monetary gains, the problem for advertisement companies such as Facebook becomes finding mechanisms to efficiently yield higher crops of user attention. To no surprise, the representation of data in Facebook’s user interface is designed to support this exact purpose.

By design. Newton’s first law of motion states that in an inertial frame of reference an object either remains at rest or continues to move at a constant velocity unless acted upon by a force. Similarly, information propagates through a network with many of the same properties that an object moving through space has. As such, information will continue to propagate through a network if external forces do not inhibit its propagation. In regard to Facebook, the mechanism that would serve to modulate the propagation of information through the network is the “Dislike” button. If there was the ability to “Dislike” information on Facebook in the same way that one can “Like” information, then the value of the information could, at a minimum, be appraised by calculating the difference between the likes and the dislikes. However, since the amount of disagreement or dislike isn’t visibly quantified, all information will always have a positive level of agreement or “Like”, giving the impression that the information is undisputedly of positive or true value.

The other prominent factor that influences the propagation of data on Facebook’s network is the amount of quantified endorsement (i.e. number of likes) a post has. In addition to Facebook’s black boxed algorithms used for Newsfeed and other content suggestions, the number of likes a piece of information has induces a psychological phenomena known as social endorsement. Social endorsement is the process of information gaining momentum (i.e. gaining more likes at a non-linear rate that accelerates with endorsement count) via the appearance of having high social endorsement, which influences other users to “Like” the information with less or no personal scrutiny at all.

Putting these factors together, consider the “Pizzagate” debacle that occurred back in 2016. Pizzagate is the name of a conspiracy theory that picked up traction on conspiracy theory websites and was subsequently amplified by Facebook through increased exposure from social endorsement and sharing. The information propagated through Facebook’s network reached a level of exposure that compelled Edgar Maddison Welch to seize the establishment with an AR-15 in order to determine if there was in fact a child prostitution ring. Needless to say, this was a false story, and he was arrested.

So what’s the big idea?

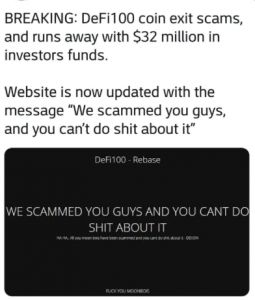

Asymmetrical representations of data on these types of ubiquitous systems perpetuate a distorted society. Whether it be a democratic election, the Pizzagate debacle, or someone losing their savings to a cryptocurrency scam video promoting some new coin with “100K Likes”; information, can reach beyond the digital realms of the internet to effect the physical world we inhabit. Ergo, the representations that we use in the tools that come to govern our society, matter.

Sources:

Kelkar, Shreeharsh. “Engineering a Platform: Constructing Interfaces, Users, Organizational Roles, and the Division of Labor.” 2018. doi:10.31235/osf.io/z6btm.

L.E. Sherman, A.A. Payton, L.M. Hernandez, et al. The Power of the “Like” in Adolescence: Effects of Peer Influence on Neural and Behavioral Responses to Social Media. Psychol Sci, 27 (7) (2016), pp. 1027-1035

Andrew Quodling PhD Candidate. “The Dark Art of Facebook Fiddling with Your News Feed.” The Conversation. May 08, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2021. http://theconversation.com/the-dark-art-of-facebook-fiddling-with-your-news-feed-31014.

Primack, Brian A., and César G. Escobar-Viera. “Social Media as It Interfaces with Psychosocial Development and Mental Illness in Transitional Age Youth.” Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. April 2017. Accessed July 9, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28314452.