Competition: A Solution to Poor Data Privacy Practices in Big Tech?

By Anonymous | July 9, 2021

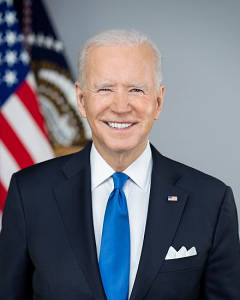

President Biden recently gave a press conference during which he spoke of a newly signed executive order on anticompetitive practices. In his introductory remarks, he highlighted the effects of a lack of competition on hearing aids. He explained, “Right now, if you need a hearing aid, you can’t just walk into a pharmacy and pick one up over the counter. You have to get it from a doctor or a specialist. Not only does that make getting hearing aids inconvenient, it makes them considerably more expensive, and it makes it harder for new companies to compete, innovate, and sell hearing aids at lower prices. As a result… a pair of hearing aids can cost thousands of dollars.” ( Biden, 2021 ) This example, however, is not unique. It explores the fundamental relationship between consumer interests and companies’ products and practices.

Commonly, it is seen that a lack of competition allows companies to charge higher prices than consumers would reasonably pay for an item under ideal competition. If there is one gas station in a town charging $4.50 per gallon of gas, people will pay $4.50 per gallon. If 9 more gas stations open up, and costs for the gas stations are equivalent to $2.50 per gallon, each gas station will lower its price per gallon to gain customers while still earning a healthy margin, resulting in a gas price that might hover around $2.70 per gallon. This results in fair pricing for residents of the town. Most people have thought about and understand this simple economic reality, but often do not think about a less tangible but equally existent application of this same effect; over-consolidation and anti-competitive practices among tech companies has led to the prevalence of poor privacy practices.

All other variables held equal, higher competition between companies causes a larger variety of products, services, and practices. As President Biden proclaimed, “The heart of American capitalism is a simple idea: open and fair competition — that means that if your companies want to win your business, they have to go out and they have to up their game; better prices and services; new ideas and products.” (Biden, 2021 ) If this is the case, as the President implies in his speech, the logical inverse is also true; lower competition between companies leads to a smaller variety of products, services, and practices. Privacy and data protection practices are one of the many casualties of low competition. Note that while not all lack of competition is due to anti-competitive practices, a lack of meaningful competition exists among tech companies nonetheless, and even those examples that are not necessarily attributable to noncompetitive practices are useful in seeing the effect of a lack of competition on privacy. If we consider the case where there is only one company providing an important or essential service, privacy practices are nearly irrelevant. If a user wants to use that service, the user must accept the privacy policy no matter its contents. Due to a lack of user-privacy focused legislation, however, current privacy policy writing and presentation practices lead a large majority of the population to almost never read a privacy policy ( Auxier et al., 2019 ).

Despite this lack of readership, which may be able to be fixed through education about privacy policies and reforms to their complexity and presentation, an increasing number of people do care significantly about data privacy practices, as can be seen by an increase in articles focused on privacy.

One example of the aforementioned lack of competition leading to poor privacy policies is Snapchat, owned by Snap, Inc. Almost everyone in the younger generations uses Snapchat, and it is not interoperable with other platforms. It can even be considered a social necessity in many groups. A user is therefore pressured into using the platform despite the severe privacy violations allowed by its terms of service and privacy policy, including Snap, Inc.’s right to save and use any user produced content – including self destructing messages ( Snap, Inc., 2019). Imagine a hypothetical society in which the network effect is a nonissue and privacy policies are easily accessible to everyone. There are three companies that offer similar services to Snapchat. Company A takes users’ privately sent pictures and uses them, stating as such in its privacy policy. Company B generally does not take users’ privately sent pictures or use them, but states in its privacy policy that it has the right to if it so chooses. Company C does not take or sell users’ privately sent pictures, and specifically states in its privacy policy that it does not have the right to do so. Company B here represents how Snapchat actually operates. Which company would you choose? Through competition, which company do you think would come out on top?

While the lack of competition in the Snapchat example is due primarily to the network effect and not documentedly to anticompetitive practices taken by Snap, Inc., promoting competition in tech more generally can lead to a change in prevailing privacy and data security practices, thus leading to a systemic shift to fairer and more private privacy and data practices.

References:

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/07/09/remarks-by-president-biden-at-signing-of-an-executive-order-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/

- https://pluspng.com/snapchat-png-9997.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joe_Biden

- https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/americans-attitudes-and-experiences-with-privacy-policies-and-laws/

- https://snap.com/en-US/terms

- https://www.snap.com/en-US/privacy/privacy-policy

- https://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/vwimages/04568-Comp-Banner.png/$file/04568-Comp-Banner.png