Regarding the University of California’s Newest Security Event

By Ash Tan | July 9, 2021

UC community.

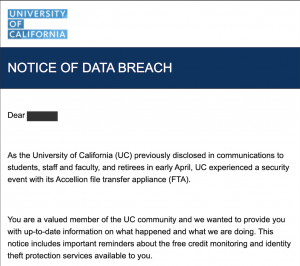

Figure 1. The University of California describes its security event in an email to a valued member of the UC community.

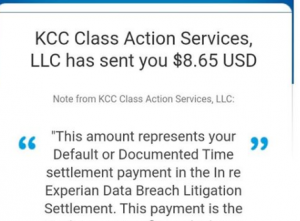

If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance that your personal data has been leaked. Important data too – your address, financial information, even your social security number could very well be floating around the Internet at this very moment. Of course, this prediction is predicated on the assumption that you, the reader, have some connection to the University of California system. Maybe you’re a student, or a staff or faculty member, or even a retired employee; it doesn’t really matter. This spring, the UC system announced that its data, along with the data of a hundred other institutions and schools, had been compromised in a euphemistically-described “security event.” In short, the UC system hired Accellion, an external firm, to handle their file transfers, and Accellion was the victim of a massive cybersecurity attack in December of 2020 (Fn. 1). This resulted in the information of essentially every person involved in the UC system being leaked to the internet, and while the UC system has provided access to credit monitoring and identity theft protection for the space of one year (Fn. 2), it should be noted that Experian, their chosen credit monitoring company, was responsible for a massive data breach of roughly 15 million people’s financial information in 2017(Fn. 3).

Perhaps the framework that applies most intuitively to this system is Solove’s Taxonomy of Privacy (Fn. 4), which compels us to seek a comparable physical analog in order to better understand this situation. One might consider the relation between paperwork and a filing cabinet: we give our paperwork to the UC, which then stores it in a filing cabinet which is maintained by Accellion. We entrust our data to the UC system with the expectation that they safeguard our information, while the UC system entrusts our data to Accellion with the same expectation. When something goes wrong, this results in a chain of broken expectations that can make parsing accountability a difficult issue. Who, then, is to blame when the file cabinet is broken into: the owner of the cabinet, or the one who manages the paperwork within?

One take is that the laws that enabled a data breach of this scale are to blame. In an op-ed piece by The Hill, two contributors with backgrounds in education research, public policy, and political science point at a certain section of California Proposition 24 that exempts schools from privacy protection requirements (Fn. 5). These exemptions, including disallowing students of the right to be forgotten, allow a greater possibility of data mismanagement/misuse. The authors Evers and Hofer claim that stronger regulatory protections could have prevented this data breach along with numerous other ransomware attacks on educational institutions across the country, and that, in line with the Nissenbaum framework of contextual privacy (Fn. 6), “opt in/out” options could have potentially limited the amount of information leaked in this event while respecting individual agency. The “right to be forgotten” could have limited the amount of leaked information regarding graduated students, retired employees, and all individuals who have exited the UC system. In addition, California currently has no defined rights that enable an individual’s right to privately pursue recompense for damages resulting from negligent data management; the authors hold that defining such rights would incentivize entities such as the UC system to secure data more responsibly.

Notably, Evers and Hofer make no mention of Nissenbaum or Solove or even the esteemed Belmont Report (Fn. 7) when prescribing their recommendations. These proposed policy changes are not necessarily grounded in a theoretical, ethical framework of abstract rights and conceptual wrongs; they are intended to minimize real-life harms of situations that have already happened and could happen again. In the context of this very close-to-home example, we can see how these frameworks are more than academic in nature. But then again, the difference between framework and policy is the same as that between a skeleton and a living, breathing creature. The question that remains to be answered is whether the UC system will take this as an opportunity to better student data protections – between GDPR and California’s more recent privacy laws, there is plenty of groundwork to draw upon – or whether they will consider it nothing more than as an unfortunate security event, the product of chance rather than the result of an increasingly dangerous digital world (Fn. 5).

References:

1. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210510005214/en/UC-Notice-of-Data-Breach

2. https://ucnet.universityofcalifornia.edu/data-security/updates-faq/index.html

3. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/oct/01/experian-hack-t-mobile-credit-checks-personal-information

4. https://www.law.upenn.edu/journals/lawreview/articles/volume154/issue3/Solove154U.Pa.L.Rev.477(2006).pdf

5. https://thehill.com/opinion/technology/550959-massive-school-data-breach-shows-we-need-better-privacy-policies?rl=1

6. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2567042

7. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/the-belmont-report-508c_FINAL.pdf

Image sources:

1. Edited from a personal email.

2. https://topclassactions.com/lawsuit-settlements/lawsuit-news/hp-printer-experian-data-breach-settlement-checks-mailed/

3. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/experian-data-breach-andrew-seldon?trk=public_profile_article_view