When It Comes to Data: Publicly Available Does Not Mean Available for Public Use

Anonymous | October 14, 2022

Imagine it’s 2016 and you’re a user on a dating platform, hoping to find someone worth getting to know. One day, you wake up and find out your entire profile, including your sexual orientation, has been released publicly and without your consent. Just because something is available for public consumption does not mean it can be removed from its context and used somewhere else.

What Happened?

In 2016, two Danish graduate research students, Emil Kirkegaard and Julius Daugbjerg Bjerrekæ, released a non-anonymized dataset of 70,000 users of the OK Cupid Platform, including very sensitive personal data such as usernames, age, gender, location, sexual orientation, and answers to thousands of very personal questions WITHOUT the consent of the platform or its users.

Analyzing the Release Using Solove’s Taxonomy

In case it wasn’t already painfully obvious, there are serious ethical issues in the way the researchers both collected and released the data. In a statement to Vox, an OK Cupid spokesperson emphasize that the researchers violated both terms of service and privacy policy of platform.

As we’ve discussed in class, users have an inherent right to privacy. OK Cupid users did not consent to have their data accessed, used, or published in the way it was. If we examine this using Solove’s Taxonomy framework, it becomes clear that the researchers violated every point he made in his analysis. In terms of information collection, this would constitute as surveillance, especially given the personal nature of the data. As for information processing, this is a gross misuse of the data and blatantly violates the secondary use and exclusion clauses. None of the users consented to having their data used for any type of study nor did they consent to having it published. The researchers argued that the data is public and that by signing up for OK Cupid, the users themselves provided that data for public consumption. This is true to an extent: the users consented to having their profile data accessed by other users of the platform—all a person had to do to access the data is create an account. What the users did not consent to was having that data be publicly available off the platform and then used by researchers not associated with OK Cupid to conduct unauthorized studies. The researchers also did not provide users with the opportunity to have a say in how their data was being used. According to Solove, exclusion is “a harm created by being shut out from participating in the use of one’s personal data, by not being informed about how that data is used, and by not being able to do anything to affect how it is used.” The researchers clearly violated every principle of Solove’s Taxonomy in every step of their process.

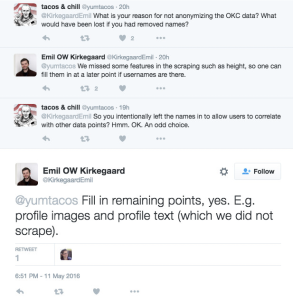

The aggregation of the data itself was unethical as they did not ask anyone for permission before scraping the website. This coupled with the fact that the researchers purposely not to make the data anonymous is beyond atrocious—the only reason the dataset did not include pictures was because they would have taken up too much space. And when asked why they didn’t remove usernames, the researchers’ response was that they wanted to be able to edit the data at a later time, in the event they gained access to more information. Let me repeat that again. They wanted to be able to edit the dataset and update user information and make the dataset as robust as possible with as much information as they could find. For example, if a user uses the same username across different platforms and had their height or race listed on a different platform, then they could crosscheck that platform and update the dataset. This also puts users at risk, particularly users whose sexuality or their lifestyle could make them targets of discrimination or hate crimes. That type of information is very private and has no place being publicized in this manner.

The dissemination of the information was a total and unethical breach of confidentiality and gross invasion of privacy. As I’ve already stated, none of the users consented to have their very sensitive personal data scraped and published in a dataset that would be used for other studies.

The Defense

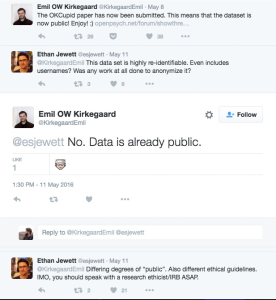

Kirkegaard defended their decision to release the dataset under the claim that the data is already publicly available. There is so much wrong with that statement.

Publicly Available Does Not Mean Available for Public Use

What does this mean? It means that just because a user consents to having their data on a platform does not mean that data can be used in whatever capacity a researcher wants. This concept also shreds the researchers’ defense. Users of OK Cupid consented to have their data used only as outlined in the company’s privacy policy and terms of service, meaning it would only be accessed by other users on the app.

What they did not consent to was having a couple of Danish researchers publish that data for anyone and everyone in the world to see. At this point in time OK Cupid was not using real names, only aliases but the idea that someone could connect an alias or username to a real life individual and access their views on everything from politics to whether they think it’s okay for adopted siblings to date each other to sexual orientation and preferences. (Yeah, I know, my hackles went up too.)

The impact this release of research had on its users is its own separate issue. Take a second to go through this blog post by Chris Girard: https://www.chrisgirard.com/okcupid-questions/. It shows the thousands of question OK Cupid users answer in their profiles, which were also released as part of the dataset.

Based off Solove’s Taxonomy, we can conclude that the researchers’ actions were unethical. Their defense was that the data was already publicly available. I argue that just because that data can be accessed by anyone who creates an OK Cupid account does not mean that it can be used for anything other than what the users have consented to. And to reiterate once again, NONE of them consented to having their data published and then used to conduct research studies both on and off the platform. Even if OK Cupid wanted to conduct an internal study on dating trends, they would still need to get consent from their users to use their data for that study.

The Gravity of the Implications and Why Ethics Matter

This matter was settled out of court and the dataset ended up being removed from the Center for Open Science (the open-source website where it was published) after a copyright claim was filed by the platform. Many people within the science community have condemned the researchers for their actions.

The fact that the researchers never once questioned the morality of their conduct is a huge cause for concern. As data scientists, we have an obligation to uphold a code of ethics. Just because we can do something does not mean we should. We need to be accountable to the people whose data we access. There is a reason that privacy frameworks and privacy policies exist. As data scientists, we need to put user privacy above all else.

https://www.vox.com/2016/5/12/11666116/70000-okcupid-users-data-release

https://www.vice.com/en/article/qkjjxb/okcupid-research-paper-dmca

https://www.vice.com/en/article/53dd4a/danish-authorities-investigate-okcupid-data-dump