Macro Impacts – Do No Harm & Where Privacy Policies Fall Short

Michael Malavé | October 14, 2022

Do No Harm in policies can help mitigate the governments and groups use/re-use/misuse their data in ways that cause harm.

When we discuss the ethical use of technologies, we inevitably visit some of history’s events where both groups and individuals of vulnerable groups were targeted and taken advantage of thanks to the lack of protections of that time. In Australia during the 19th and 20th centuries, the Aborigines underwent forced migration and elements of genocide were present. Here, a population registration was used. Across France, Germany, Norway, Poland, and Romania, both population and special census were used in the process of forced migration and genocide of Jews. In both cases, these data collected across a population were used to expedite the acts. We also view the case of Henrietta Lacks who sought treatment but instead had her blood sampled and studied in perpetuity, with neither consent or benefit.

Policies meant to mitigate incorrect use of these data might prevent effectiveness of such events and the ability for data to bolster their efforts. In the US, the Census agency and its practice has a very thoughtful design of privacy that includes the way their agency shares data across other agencies to its limitation to a single exception of the Secretary of Commerce according to its Code 9 exception. Moreover, the direct use of the data by government bodies cannot be used for any “purpose other than the statistical purposes for which it is supplied”1 This clear language on the limited usage of the data and its limitations in access seem a model for a well designed process and policy. But is that sufficient?

A response rate dashboard on the U.S. Census site. Includes an outreach email, timeliness of data, a link to technical details. [2]

“In practice, Do no Harm means that biometrics and digital identity should not be used by the issuing authority, typically a government, to serve purposes that could harm the individuals holding the identification. Nor should it be used by adjacent parties to the system to create harm.”[3]

Here, Dixon communicates harm in a context where collections are also including biometric data (fingerprints, palm prints or other unique identification). “One of the most significant changes is the precipitous decline of privacy by obscurity, which is essentially a form of privacy afforded to individuals inadvertently by the inefficiencies of paper and other legacy recordkeeping.” Dixon identifies the Aadhar system which tracks individual level data along with biometric markers for them. This system models an extreme of technology outpacing the policy where no policy was prepared or developed alongside it to dictate its usage of the id. Initially used to enable access to government subsidies, the role has increased to, “bank accounts, medical records, pension payments, and a seemingly ever-growing list of activities.”3 This increase of who has access to this data and what it might be used for has far less limitations than that of the U.S Census while also having over one billion people enrolled.

This web of access to centralized data might be impactful to vulnerable populations for whom knowledge of their health data, for example, might result in stigma and decisions being made based on that information. From these negative impacts, we might quickly see how

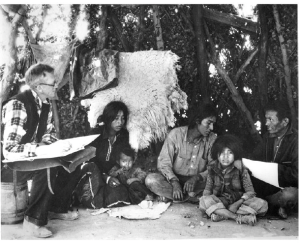

In addition to the re-identification and related forms of misuse of that data, harm may also be caused through inaccuracies. This very issue was raised by the National Congress of Native American Indians in a letter to the Acting Director of the U.S. Census Bureau.

We have stated on multiple occasions that the 2020 Census data must be accurate and usable for the following priority use cases: 1) reapportionment and representation; 2) federal funding formulas and decision-making; 3) local tribal governance; and 4) AI/AN research and public health surveillance/trend data.[5]

By even considering applying U.S. Census Bureau’s policies to Aadhaar, we can start to see how the Aadhaar’s listed potential impacts might be mitigated. Yet by the definition of harm, we also find these policies including limiting access to discrete data, intentionally obscuring data to minimize success in re-identification, limiting use of data to specified purpose, are insufficient in protection of the American Indians and Alaska Natives from inaccurate data. Inaccurate data of their populations from the U.S. Census may inform policies that put at risk their very sovereignty and so inaccurate counts can be very high stakes. Taking Pam Dixon’s recommendation for Aadhaar, I further recommend that the U.S Census policies be updated to include a Do No Harm clause.

References:

1. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/13/9

2. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/2020-census-self-response-rates-map.html

3. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12553-017-0202-6

4. https://www.dynamsoft.com/blog/imaging/barcode/how-to-extract-aadhaar-card-information/

5. https://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/research-data/prc-publications/Dr._Ron_S._Jarmin_-_US_Census_Bureau_2020_Census_NCAI-_May_25,_2021.pdf

6.https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/censuses_of_american_indians.html