It is Time to Revisit HIV Public Health Practices

By Jackie Nichols | October 7, 2021

For over 15 years, I’ve been working with organizations whose mission is to end AIDS. My passion stems from growing up in the 1980’s when the deadly disease became its most prominent and fear gripped us all. Stories that I had been reading about or seeing on the news became a part of my life. Several of my friends had contracted AIDS and sadly lost their lives to the disease. As we learned more about the disease, fear subsided, and I fell trap to naively believing that AIDS was a thing of the past. It wasn’t until years later that a friend asked for a donation for the 2006 NY AIDS walk that I realized my naivety. I had managed to push the uncomfortable topic of HIV/AIDS out of my thoughts since the disease was no longer as prominent in my day-to-day life. I was also shocked that AIDS hadn’t been defeated yet and that there was so much more work to do. Work that centered around public health practices.

Public Health

The CDC estimates there are as many as 1.2 million Americans infected with HIV with approximately thirteen percent of them unaware (U.S Statistics, 2021). In Los Angeles alone, it’s estimated that a quarter of all people diagnosed with AIDS during 1990 – 1995 only became aware of their infection when they exhibited advanced symptoms and received care at a hospital or clinic (Burr, 1997). This would mean that they would have most likely been HIV-positive for years and perhaps spreading the disease unknowingly. While it’s true that an HIV-positive patient will require a lifetime of costly treatment, estimated at $4,500 each month per patient (How Much Does HIV Treatment Cost?, 2020), it’s the CDC’s belief that even just one notification out of eighty pays for itself by preventing any new HIV infections (Burr, 1997). With HIV being treatable, it seems like we should be doing more to test for the disease and notify others as early as possible. Imagine the outrage if the US stopped routine testing for breast, ovarian or colon cancer and only treated patients upon admission to a hospital due to exhibiting advanced symptoms.

Contact Tracing

If you didn’t know what contact tracing was before the pandemic, there’s a good chance you know now. I’m sure most of us have heard public officials say that we must do our part to “flatten the curve” when referring to the COVID-19 pandemic. Flattening the curve refers to keeping the number of reported COVID-19 cases as low as possible, accounting for the load on our health care system. Contact tracing is one process that can help flatten the curve by identifying persons who may have come in contact with an infected person (“contacts”) and subsequent collection of further information about these contacts.

The goal of contact tracing is to reduce infections in the population by tracing the contacts of infected individuals, testing the contacts for infection, and isolating or treating the infected, and then tracing their contacts. Contact tracing is just one measure against an infectious disease outbreak and often requires some of the following steps be taken in conjunction: routine testing and in most cases without explicit patient consent, reporting the names of those who test positive to local health authorities, and notification to those that were in contact with the infected person that they may been exposed to. Those being notified should receive only the information they really need to maintain the privacy and anonymity of the infected individual.

Contact tracing isn’t new. In fact, it’s been used for centuries and has been one practice in the fight against infectious disease outbreaks that include tuberculosis, diphtheria, typhoid and now COVID-19. It’s intriguing that HIV, an epidemic responsible for more than an estimated 700,000 deaths in the US since 1981 (Cichocki, 2020), isn’t routinely tested for, and when it is it requires explicit patient consent. The names of those who do test positive for HIV are not reported to local health authorities making contact tracing impossible.

Why Do We Treat HIV so differently?

To understand why testing, contact tracing and notification for HIV/AIDS is so different from other infectious diseases, we need to look back to the 1980’s and at what drove the ignorance and fear through four very common beliefs (Burr, 1997):

- The disease was first called Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID) by researchers leading the public to believe that AIDS was limited to homosexuals and in fact a marker of homosexuality.

- The stigma associated with AIDS and how the disease is transmitted would make it impossible to maintain any level of testing confidentiality.

- There was a limited understanding of how the disease was spread with sexual transmission believe to be the only method. It was believed that HIV is only transmitted through sex, which is a taboo subject in some cultures. With the stigma associated with people who contracted AIDS, it was felt that contact tracing would be ineffectual due to the large number of sexual partners of those infected.

- AIDS was so different and limited to who it affected, with no cure or treatment, it was believed that it would be pointless to report HIV infection as is done for other infections. There was an early belief that the disease would “run its course”.

The damage of these four beliefs was significant and is still felt to this day. While many in the US have learned and believe that the disease is not a homosexual marker, testing, contact tracing along with privacy and stigma remain as challenges.

Testing for HIV

Being admitted to any hospital or ER today in the US typically involves patient blood work that is tested for various diseases (e.g., tuberculosis) as well as the patient being tested for COVID-19. The blood work and COVID-19 tests occur without patient consent and are generally an accepted societal norm, i.e., people do not question that they will be tested when being admitted to a hospital. Similarly, a lot of work has been undertaken to reach similar norms for yearly wellness checks for women to test for breast and ovarian cancer, and for routine checks for colon cancer in the general population. According to Nisenbaum, this is what she refers to as contextual integrity; privacy holds when context-relative informational norms are respected; it is violated when they are breached (Nissenbaum, 2008).

Unlike other infectious diseases, testing for HIV requires explicit patient consent and is currently prohibited in every state. Blood banks are the exception as they test and screen for HIV but do not perform notifications should a sample be found to be infected. Blood banks maintain privacy by following existing legislation and social norms but in doing so, potentially allow the spread of the disease to continue. Interestingly, AIDS infections must be reported in all fifty states, but HIV does not have the same requirement once again skirting the proven methods of tracing infectious diseases. For those states that do report HIV-positive results, all personal information is removed from the test results prior to sending to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to monitor what is happening with the HIV epidemic.

Partner Notification

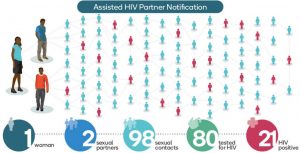

The CDC has various outreach efforts that they refer to as “Partner notification” which includes contact tracing. This involves patients volunteering for a test, and public-health officials locating and notifying partners of infected people of possible infection. This process hinges on people being willing or able to share the names of their partners. Privacy is maintained by keeping the infected patients name confidential, although that does not always guarantee anonymity. In most states there is no legal obligation to disclose your HIV-positive status to your current or past partners (Privacy and Disclosure of HIV Status, 2018).

The goal with HIV partner notification is to minimize the spread of the disease, and to treat the disease as early as possible before reaching the late stage of AIDS. AIDS is stage 4 and typically occurs when the virus is left untreated. The earlier the virus is detected, the more manageable the disease for the individual through antiretroviral drugs. Partner notification requires two things to be successful: people must be willing to be tested and provide the results, and people must be able to act on the information. For this to happen at a scale needed to combat HIV, the privacy of the infected individuals must be protected from unnecessary disclosure. With the data breaches that plague our digital world, one’s privacy isn’t a guarantee making HIV contact tracing more challenging than other infectious diseases.

The Impact of Stigma on HIV Public Health Policies

Stigma is one of, if not the biggest blocker from mandating HIV and AIDS testing and reporting in advancing the public health policies around HIV. Whenever AIDS has won, stigma, shame, distrust, discrimination and apathy was on its side (HIV Stigma and Discrimination, 2019). HIV stigma refers to irrational or negative attitudes, behaviors, and judgments towards people living with or at risk of HIV (Standing Up to Stigma, 2020). When people are identified as HIV-positive there is a risk of being stigmatized and being discriminated against. Some of the beliefs that originated in the 1980’s still exists and in some areas in the US, thrive, e.g., HIV/AIDS is a homosexual marker. While we have made progress in gay rights and equality, being identified as a homosexual can still lead to harassment, discrimination, abuse, and violence. People are aware of the stigma and the risk associated with being publicly identified as HIV-positive and as a result many people avoid accepted public health practices like testing and reporting when it comes to HIV. In the 1980s and 1990’s the driving force for many of the legal cases involving protecting the privacy of patients was driven by the stigma associated with AIDS and the risk of being publicly identified as HIV-positive. While section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) were updated to protect the civil and workplace rights of people living with HIV and AIDS (Civil Rights, 2017), many people still feel it’s not enough given the power of societal judgement and the way harassment and abuse can manifest itself causing harm to the infected individual. As a result, we are left with HIV being exempt from consent free testing and reporting, only requiring that AIDS be reported in all fifty states, and a disease that is allowed to go undetected and untraced potentially harming others unknowingly.

Closing Thoughts

Forty years later, it’s clear that when addressing the issue of HIV and public health practices stigma plays a significant role. When considering the broader public health question of how you can control a disease if you decline to find out who is infected (Shilts, 1987) is at the core of the battle to end AIDS. It’s clear that we must first defeat the HIV stigma which will allow for the implementation of better public health practices that are needed to end AIDS.

References

1980s HIV/AIDS Timeline (2017) Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pi/aids/youth/eighties-timeline on September 26, 2021

Burr, C (1997) The AIDS Exception: Privacy vs. Public Health Retrieved from The AIDS Exception: Privacy vs. Public Health – The Atlantic on September 10, 2021

Cichocki, M (2020), How Many People Have Died of HIV? Retrieved from https://www.verywellhealth.com/how-many-people-have-died-of-aids-48721 on September 25, 2021

Civil Rights (2017), Laws Protect People Living with HIV and AIDS Retrieved from https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/living-well-with-hiv/your-legal-rights/civil-rights on September 30, 2021

HIV Stigma and Discrimination (2019) Retrieved from https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-social-issues/stigma-discrimination on October 1, 2021

How Much Does HIV Treatment Cost? (2020) Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/hiv-treatment-cost on September 29, 2021

Laws Protect People Living with HIV and AIDS (2017) Retrieved from https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/living-well-with-hiv/your-legal-rights/civil-rights on September 30, 2021

Privacy and Disclosure of HIV Status (2018) Retrieved from https://www.justia.com/lgbtq/hiv/privacy-disclosure on September 30, 2021

Standing Up to Stigma (2020 ) Retrieved from https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/making-a-difference/standing-up-to-stigma on September 28, 2021

U.S Statistics (2021) Retrieved from https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics on September 20, 2021