AI the Biased Artist

Alejandro Pelcastre | July 5, 2022

Abstract

OpenAI is a machine learning technology that allows users to feed it a string of text and output an image that tries to illustrate such text. OpenAI is able to produce hyper-realistic and abstract images of the text people feed into it, however, it is plagued with tons of gender, racial, and other biases. We illustrate some of the issues that such a powerful technology inherits and analyze why it demands immediate action.

OpenAI’s DALL-E 2 is an updated emerging technology where artificial intelligence is able to take descriptive text as an input and turn it into a drawn image. While this new technology possesses exciting novel creative and artistic possibilities, DALL-E 2 is plagued with racial and gender bias that perpetuates harmful stereotypes. Look no further than their official Github page and see a few examples of gender biases:

The ten images shown above all depict the machine’s perception of what a typical wedding looks like. Notice that in all the images we have a white man with a white woman. Examples like these vividly demonstrate that this technology is programmed in a way that depicts the creators’ and the data’s bias since there are no representations of people of color or queer relationships.

In order to generate new wedding images from text, a program needs a lot of training data to ‘learn’ what constitutes a wedding. Thus, you can feed the algorithm thousands or even millions of images in order to to ‘teach’ it how to envision a typical wedding. If most of the images of weddings depict straight heterosexual young white couples then that’s what the machine is going to learn what a wedding is. This bias can be overcome by diversifying the data – you can add images of queer, black, brown, old, small, large, outdoor, indoor, colorful, gloomy, and more kinds of weddings to generate images that are more representative of all weddings rather than just one single kind of wedding.

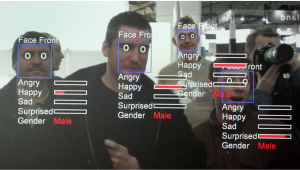

The harm doesn’t stop at just weddings. OpenAI illustrates other examples by inputting “CEO”, “Lawyer”, “Nurse”, and other common job titles to further showcase the bias embedded in the system. Notice in Figure 2 the machine’s interpretation of a lawyer are all depictions of old white men. As it stands OpenAI is a powerful machine learning tool capable of producing novel realistic images but it is plagued by bias hidden in the data and or the creator’s mind.

Why it Matters

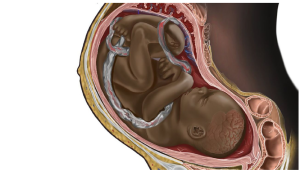

You may have heard of a famous illustration circling the web recently that depicted a black fetus in the womb. The illustration garnered vast attention because it was surprising to see a darker tone in medical illustration in any medical literature or institution. The lack of diversity in the field became obvious and brought into awareness the lack of representation in the medical field as well as disparities in equality that seem invisible to our everyday lives. One social media user wrote, “Seeing more textbooks like this would make me want to become a medical student”.

Similarly, the explicit display of unequal treatment for minority people in OpenAI’s output can have unintended (or intended) harmful consequences. In her article, A Diversity Deficit: The Implications of Lack of Representation in Entertainment on Youth, Muskan Basnet writes: “Continually seeing characters on screen that do not represent one’s identity causes people to feel inferior to the identities that are often represented: White, abled, thin, straight, etc. This can lead to internalized bigotry such as internalized racism, internalized sexism, or internalized homophobia.” As it stands, OpenAI perpetuates harm not only on youth but to anyone deviating from the overrepresented population that is predominantly white abled bodies.

References:

[1] https://github.com/openai/dalle-2-preview/blob/main/system-card.md?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Future%20Perfect%204-12-22&utm_term=Future%20Perfect#bias-and-representation

[2] https://openai.com/dall-e-2/

[3] https://www.cnn.com/2021/12/09/health/black-fetus-medical-illustration-diversity-wellness-cec/index.html

[4] https://healthcity.bmc.org/policy-and-industry/creator-viral-black-fetus-medical-illustration-blends-art-and-activism

[5] https://spartanshield.org/27843/opinion/a-diversity-deficit-the-implications-of-lack-of-representation-in-entertainment-on-youth/#:~:text=Continually%20seeing%20characters%20on%20screen,internalized%20sexism%20or%20internalized%20homophobia.