Websites use privacy popups to track you on every website you visit.

Francisco Valdez | June 23, 2022

Privacy Notice popups are annoying, and people are ignoring them. But, they do more than just asking for consent to store cookies.

When GDPR came into effect on May 25th, 2019, we saw privacy notice popups on websites suddenly appear, and the constant battle to keep our information private began to gain awareness. Although GDPR didn’t specify any mechanism to provide consent, the European ad industry implemented the privacy notice popups even before the law came into effect. The privacy notice popups have many goals. The most important goal is to inform users about how they are being tracked and provide a mechanism to opt out. Then the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) became effective on January 1st, 2020, providing similar protections to California residents. CCPA additionally requires an easy and accessible way to opt out. [1]

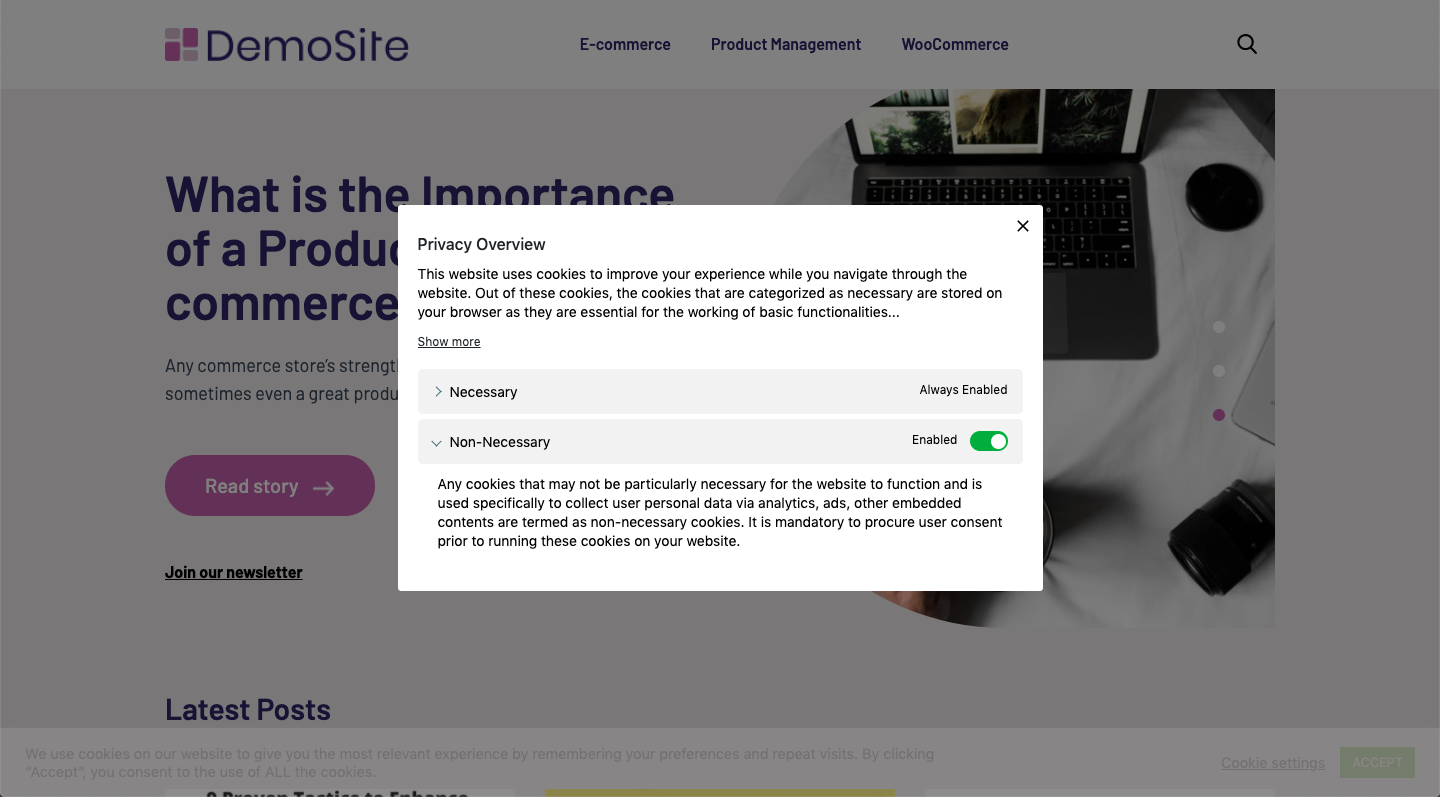

Most websites use third-party Consent Management Providers (CMP) that provide plugins to implement the privacy notice popups. When users consent, they store a cookie with the response given.

Example of a Privacy Notice popup. Image by WordPress Cookie Notice plugin https://wordpress.org/plugins/cookie-notice/

Nowadays, people consent to privacy notices without reading them to be able to access the content they want. When you consent to be tracked, you do not only agree to store cookies for that particular website on your device. You also agree to access existing data on your device, such as third-party cookies, advertising identifiers, device identifiers, and similar technologies. Also included in the consent is a provision to personalize advertising and content for you on other websites or apps. In addition, your actions on other sites or apps are utilized to make inferences about your interests, influencing future advertising or content.

Many websites have illegally made it harder to opt out by making you read super long privacy notices before you can opt out. Or they make you hop through different pages to show you the opt-out button. Other websites don’t even provide an opt-out. And when you are lucky enough to find the opt-out button, some websites ignore your decision [2].

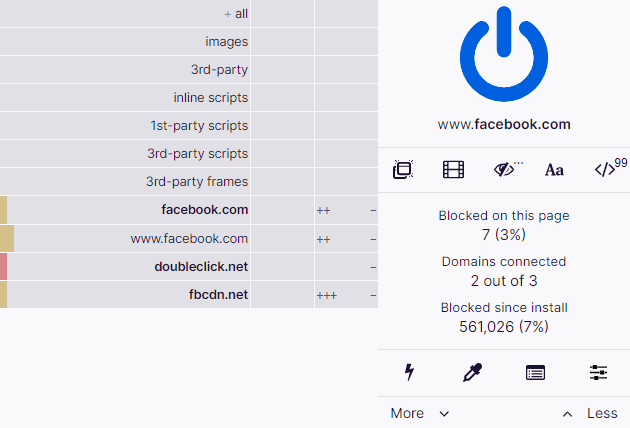

uBlock Origin in action. Image by uBlock Origin https://ublockorigin.com/

There are many countermeasures for websites that make it harder to opt out. First, you can install an ad-blocker. Ad-blockers have gained popularity in the past few years, but at the same time, it’s becoming an arms race. Publishers are always looking for ways of evading ad-blockers, and ad-blockers are always trying to detect ads and tracking signals. As a result, some publishers have made arrangements with ad-blockers to provide easy opt-out mechanisms and unobtrusive ads; these publishers can bypass

ad-blockers. Ad-blockers generally stop websites from storing cookies in your browser and block tracking signals [3]. Since websites are constantly trying to evade ad-blockers, using them may interfere with the website’s correct functioning.

Do Not Track initiative logo. Image by https://www.eff.org/issues/do-not-track

An additional layer of protection is to enable your Do-Not-Track (DNT) signals in your browser. The problem with current opt-out mechanisms is that they require you to store a cookie with your consent decision on your device. Also, you would need to opt out of every website you use. So instead of opting out constantly, DNT is a setting stored in your browser, which signals every website you visit with your privacy preferences [4]. DNT is consistent with GDPR and CCPA. Both frameworks consider a mechanism where the users configure their devices to store their privacy preferences. For this to be a successful mechanism, mass adoption from all the stakeholders is required.

In summary, Privacy Notice popups are becoming annoying, and the only viable path forward is for mass adoption of Do-Not-Track. Consumers are also responsible for reporting websites not compliant with GDPR, CCPA, or any other regional privacy law.

References

[1]

Kamala D. Harris, Attorney General, California Department of Justice (2014, May). Making Privacy Practices Public. Retrieved from https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/cybersecurity/making_your_privacy_practices_public.pdf

[2]

C. Matte, N. Bielova, and C. Santos (2019, May) Do Cookie Banners Respect my Choice?. ANR JCJC PrivaWeb ANR-18-CE39-0008. Retrieved from http://www-sop.inria.fr/members/Nataliia.Bielova/papers/Matt-etal-20-SP.pdf https://www-sop.inria.fr/members/Nataliia.Bielova/cookiebanners/

[3]

uBlock Origin. About uBlock Origin. Retrieved (2022, June) from https://ublockorigin.com/

[4]

Dan Goodin (2020, October 8th) Now you can enforce your privacy rights with a single browser tick. Ars Technica. Retrieved from https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2020/10/coming-to-a-browser-near-you-a-new-way-to-keep-sites-from-selling-your-data/