Predictive Models as a Means to Influence Consumer Behavior

By Erick Martinez | March 9, 2022

Background

The world’s largest and most successful tech companies have built their wealth selling ads and promoting various products and services. A significant portion of that success comes from their ability to market and personalize ads down to the individual level, to serve ads which are continuously more and more “relevant” to the consumer. As tech continuously amasses even more granular data and develops increasingly sophisticated models, will their influence become a problem for individual decision making? Should we or could we set a practical ethical limit on the improvement of potent stimuli based on deep learning and other predictive analyses relying on big data? I don’t think there’s any present evidence to support the idea that tech companies can direct our every move in some sort of apocalyptic post-modern sci-fi sort of way. I do believe however, that tech companies have a degree of influence over their users which is at best, significantly persuasive and at worst, manipulative and coercive.

Due Process

I’d like to borrow a legal framework that applies quite directly to our case. Due process outlines the entitlements allowed to an individual throughout their treatment in various legal settings. The need to expand the rights of individuals with respect to big data based systems is echoed in “Big Data and Predictive Reasonable Suspicion”, which concerns the extent to which law enforcement can apply big data based systems in order to “know” a suspect [1]. Such systems circumvent the protections afforded to every citizen against unreasonable search and seizure as from predictive models and extensive databases, law enforcement can justify the seizure of a suspect, a far cry from the limited “small” data afforded by law enforcement in traditional settings [1]. In our consumer structure adequate due process would allow for an individual to appeal a specific model’s determination, their data sources, the extent of personalization permitted in the advertisements they receive, and the persuasive methods found to be effective against an individual. Due process would have been especially useful for Uber drivers as detailed in “How Uber Uses Psychological Tricks to Push Its Drivers’ Buttons” by the New York Times.

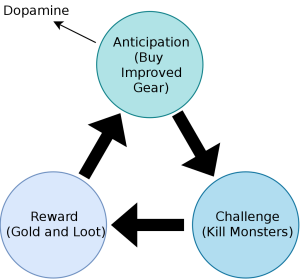

Uber made use of various known behavioral science mechanisms: loss aversion, income targeting, compulsion looping, all informed by the massive amounts of data collected on their drivers [2]. Similar techniques can be seen in social media/entertainment sites such as Google, Facebook, Instagram, etc. The fear of missing out on a particular aspect of social groups is reinforced by the ephemeral posting structures of such platforms and mirrors the loss aversion tactics employed by Uber. Compulsion looping is exemplified via the transition to an endless scroll as well as the timed nature of various push notifications; these mechanisms serve to confine the user in a loop of anticipation, challenge, and reward [3].

Conclusion

Users should be able to see how their actions are being influenced and to what extent they are affected; they should be able to see which features factor into how ads are presented and structured within the platform whenever that structure is informed by the data gathered on the individual. The lack of such information was harrowing in the case of Uber drivers, since drivers are independent contractors they cannot be compelled to work a specific schedule, however from insights garnered from the data they have on their drivers they were able to compel drivers to specific locations which was more profitable for Uber but was not necessarily more profitable for the driver. A similar argument is made from digital media companies: offering up more of your data helps make ads more relevant for you, a benefit for the consumer as it’s often framed. However relevant ads are very profitable for such entities and users might not be so keen on the ads no matter their relevancy [4].

References

[1] [Big Data and Predictive Reasonable Suspicion. Andrew Guthrie Ferguson](https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2394683)

[2] [How Uber Uses Psychological Tricks to Push Its Drivers’ Buttons. New York Times](https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/04/02/technology/uber-drivers-psychological-tricks.html)

[3] [The Compulsion Loop Explained. Game Developer](https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/the-compulsion-loop-explained)

[4] [Experiencing Social Media Without Ads. Zhivko Illeieff](https://medium.com/swlh/experiencing-social-media-without-ads-56576974b40b)