What do GDPR and the #MeToo Movement Have in Common?

By Asher Sered | October 21, 2018

At first glance it might be hard to see what the #MeToo movement has in common with the General Data Protection Rule (GDPR), the new monumental European regulation that governs the collection and analysis of commercially collected data. One is a 261 page document composed by a regulatory body while the other is a grassroots movement largely facilitated by social media. However, both are attempts to protect against commonplace injustices that are just now starting to be recognized for what they are. And, fascinatingly, both have brought the issue of consent to the forefront of public consciousness. In the rest of this post, I examine the issue of consent from the perspective of sexual assault prevention and data privacy and lay out what I believe to be a major issue with both consent frameworks.

Consent and Coercion

Feminists and advocates who work on confronting sexual violence have pointed out several issues with the consent framework including the fact consent is treated as a static and binary state, rather than an evolving ‘spectrum of conflicting desires’[1]. For our purposes, I focus on the issue of ‘freely given’ consent and coercion. Most legal definitions require that for an agreement to count as genuine consent, the affirmation must be given freely and without undue outside influence. However, drawing a line between permissible attempts to achieve a desired outcome and unacceptable coercion can be quite difficult in theory and in practice.

Consider a young man out on a date where both parties seem to be hitting it off. He asks his date if she is interesting in having sex with him and she says ‘yes’. Surely this counts as consent, and we would be quick to laud the young man for doing the right thing. Now, how would we regard the situation if the date was going poorly and the man shrugged off repeated ‘nos’ and continued asking for consent before his date finally acquiesced? What if his date feared retribution if she were to continue saying ‘no’? What if the man was a celebrity? A police officer? The woman’s supervisor? At some point a ‘yes’ stops being consent and starts being a coerced response. But where that line is drawn is both practically and conceptually difficult to disentangle.

Consent Under GDPR

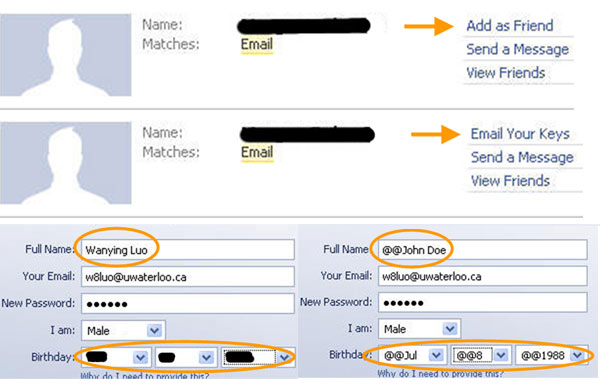

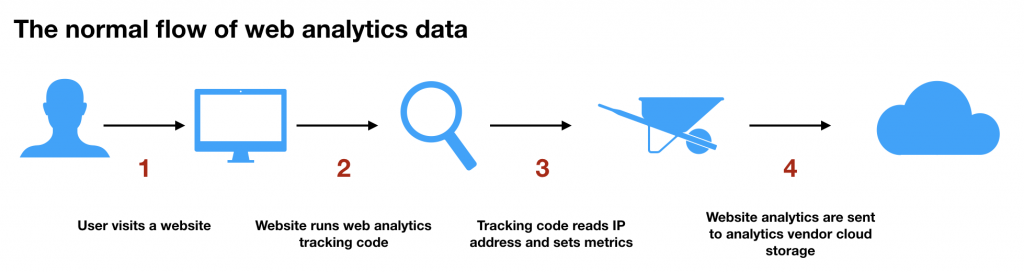

The authors of GDPR are aware that consent can also be a moving target in the realm of data privacy, and have gone to somelengths to try and articulate under what conditions an affirmation qualifies as consent. The Rule spends many pages laying out the specifics of what is required from a business trying to procure consent from a customer, and attempts to build in consumer protections that shield individuals from unfair coercion. GDPR emphasizes 8 primary principles of consent, including that consent be easy to withdraw, free of coercion and given with no imbalance in the relationship.

How Common is Coercion?

Just because the line between consent and coercion is difficult to draw doesn’t necessarily mean that the concept of consent isn’t ethically and legally sound. After all, our legal system rests on ideas such as intention and premeditation that are similarly difficult to disentangle. Fair point. But the question remains, in our society how often is consent actually coerced?

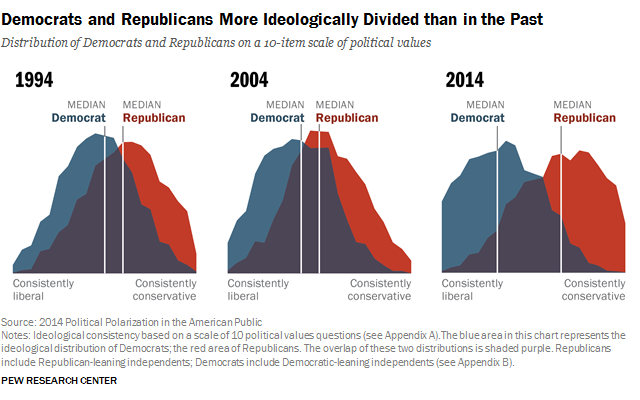

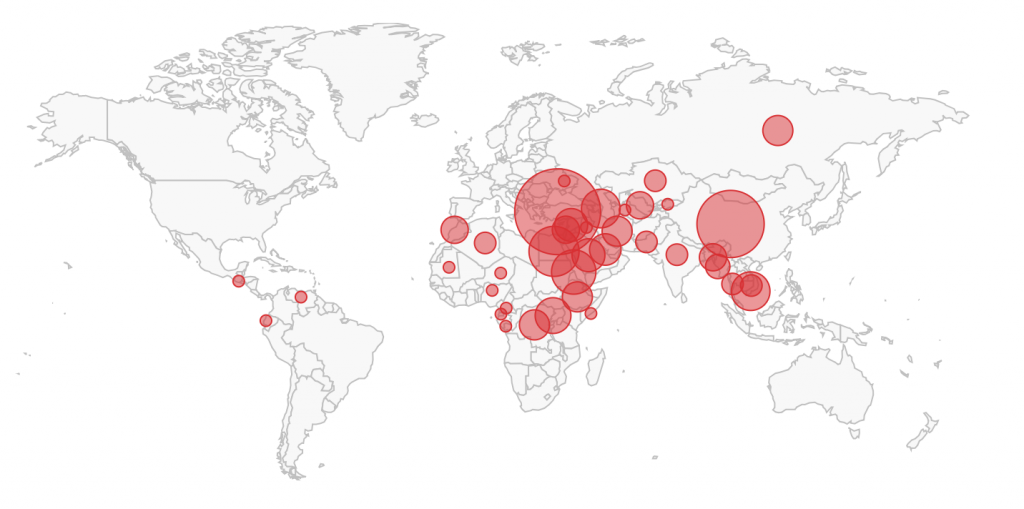

Michal Buchhandler-Raphael, a professor of Law at Washington and Lee University, argues that problems with legal frameworks in which the definition of rape is built around non-consensual sex ‘[are] most noticeable in the context of sexual abuse of power stemming from professional and institutional relationships.[2]’ She cites numerous cases in which a supervisor or someone in an otherwise privileged position managed to extract consent from a subordinate, and was therefore unpunished by the legal system. Since 70% of rapes are committed by someone known to the victim, and presumably an even larger percentage of sexual interactions take place between parties who know each other, we can expect that some amount of coercion occurs in numerous day to day sexual interactions. Especially given the fact that we continue to live in a patriarchal society where men are much more likely than women to be in positions of power[3].

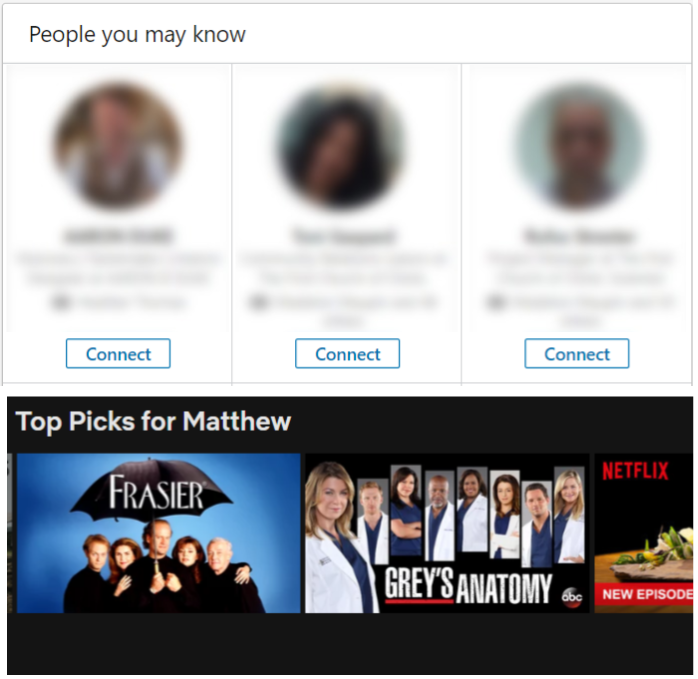

This observation about power imbalances in sexual interactions neatly parallels a major concern with consent under GDPR. While GDPR requires that data subjects have a ‘genuine or free choice’ about whether to give consent, it fails to adequately account for the fact that there is always a power differential between a major corporation and a data subject. Perhaps I could decide to live without email, a smartphone, social networks or search engines, but giving up those technologies would have a major impact on my social, political and economic life. It matters much more to me that I have access to a Facebook account than it does to Facebook that they have access to my data. If I opt out, they can sell ads to their other 2 billion customers.

Conclusion

I should be clear that I do not intend to suggest that companies stop offering Terms and Conditions to potential data subjects or that prospective sexual partners stop seeking affirmative consent. But we do need to realize that consent is only part of the equation for healthy sexual relationships and just data practices. The next step is to think about what a world would like where people are not constantly pressured to give things away, but instead are empowered to pursue their own ends.

Notes

[1] See, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/thoughts-on-metoo-why-cant-men-understand-the-concept-of-consent-a-flimmaker-explains/articleshow/66198444.cms?from=mdr&fbclid=IwAR0O8fzj4cQ4d68nwqWciQPSLrepZIV00RJKAnUmsC0id6JBqnNb4CR69WQ for a fascinating take on the topic

[2] https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=mjgl

[3] Of course, coercion can be used by people of all genders to convince potential partners to agree to have sex.