Authentication and the State

By Julie Nguyen

Introduction

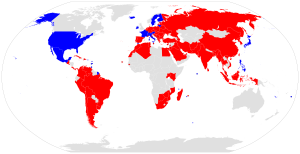

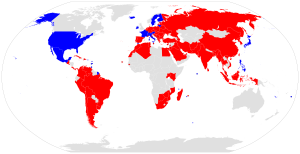

For historical and cultural reasons, the American society is one of very few democracies in the world where there is no universal authentication system at the national level. Surprisingly, the Americans don’t trust governments as they do toward corporations because they consider such identifier system a serious violation of privacy and a major opening to Big Brother government. I will argue that it is more beneficial for the US to create a universal authentication system to replace the patchwork of de facto paper documents currently in use in a disparate fashion at the state level in the United States.

Though controversial and difficult to be implemented, a national-level authentication system would entail a lot of benefits.

It is not reasonable to argue that it is too complex to create a national-level authentication system. No, it is hard but possible elsewhere.

The debate on a national-level authentication system is not new. In Europe, national census scheme inspired a lot of resistance as it tended to focus the attention on privacy issues. One of the earliest examples was the protest against a census in the Netherland in 1971. Likewise, nobody foresaw the storms of protests over the censuses in Germany in 1983 and 1987. In both countries, the memories of the World War II and how the governments had terrorized the Dutch and German people during and after the war could explain such kind of reactions.

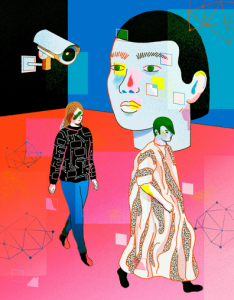

Similarly, proposals for a national-level identity cards produced the same reactions in numerous countries. Today, however, almost all modern societies have developed systems to authenticate their citizens. Those systems have evolved with the advent of new technologies in particular the biometric cards or e-cards: the pocket-sized “ID cards” have become biometric cards in almost all European countries and E-cards in Estonia. Citizens of many countries, including democracies, are required by law to have ID cards with them all the time. Surprisingly, these cards are still viewed by Americans as a major tool of oppressive governments and any discussion on establishing a national-level ID cards are not in general considered fit for discussion.

In some countries where people shared the same American view, their governments have learnt their hard lessons. As the result, contemporary national identification policies tend to be introduced more gradually under other symbols than the ID system per se. Thus, the new Australian policy is termed an Access Card since its introduction in 2006. The Canadian government now talks of a national Identity Management policy. More recently, the Indian government has implemented Aadhaar, the biggest world-wide biometric identification scheme containing the personal details, fingerprints and iris patterns of 1.2 billion people – nine out of ten Indians.

It is time that the federal government, taking lessons from other countries, create a national-level authentication system in the Unites States given that the system would create a lot of benefits for the Americans.

The advantages of a national authentication system would outperform its disadvantages in contrast to the argument of the opponents related to privacy and discrimination issues. I will use two main arguments to justify my statement. First and foremost, the most significant justification for identifying citizens is to insure the public’s safety and well-being. Even in Europe where the right to privacy is extremely important, Europeans have made a trade-off in favour of their safety. Documents captured from Al Queda or ISIS show that terrorists are aware that anonymity is a valuable tool for penetrating an open society. For domestic terrorist acts, it would be also easier and simpler to get terrorists caught in the case the country has a universal authentication system. For instance, Unabomber is one of the most notorious terrorists in the United States due to fact that it was extremely hard to track him as he had quasi no identity in the society.

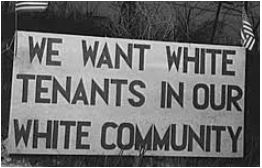

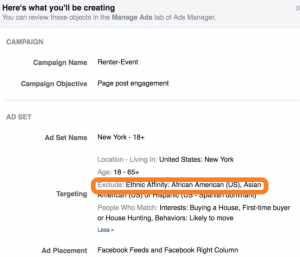

Second, the opponents of a national authentication system argue that traditional ID cards or a national authentication system are a source of discrimination. Actually, universal identifiers could serve to reduce discrimination in some areas. All job applicants would be identified to avoid the fake identity, not only immigrant people or those who look or sound “foreign”. Taking the example of E-Verify which is a voluntary online system operated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in partnership with the Social Security Administration (SSA). It’s used to verify an employee’s eligibility to legally work in the United States. E-Verify checks workers’ Form I-9 information for authenticity and work authorization status against SSA and Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS) database. Today, more than 20 states have adopted laws that require employers to use the federal government’s E-Verify Program. As the E-verify entails further administrative costs for potential employers, it is a driver of discrimination towards immigrant workers in the United States. A national “E-verify” system of all US residents would prevent such a source of discrimination.

Lack of a national-wide authentication system results in a lot of social costs.

Identity theft has become a serious problem in the United States. Though the federal government passed the Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act in 1998 in order to crackdown the problem and make it a federal felony, the cost of identity theft has continued to increase significantly[1]. Identity thieves have stolen over $107 billion in the US for the past six years. Identity theft is particularly frightening because there is no completely effective way for most people to protect themselves. Rich and powerful persons can be also caught in the trap. For example, Abraham Abdallah, a busboy in New York, succeeded in stealing millions of dollars from famous people’s bank accounts, using the Social Security Numbers, home addresses and birthdays of Warren Buffet, Oprah Winfrey and Steven Spielberg…

People usually think that identity theft is mainly a case of someone using another person’s identity to steal money from this person, mostly via stolen credit cards or more complicated in the case of the above-mentioned New Yorker. But the reality is much more complex. In his book The Limits of Privacy, Amitai Etzioni lists several categories of crime related to identity theft:

-

- Criminal fugitive

- Child abuse and sex offenses

- Income tax fraud and welfare fraud

- Nonpayment of child support

- Illegal immigration

Additionally, the highest hidden cost for American society due to the lack of a universal identity system is, in my opinion, the vulnerability of their democracy and the inefficient function of the whole society. In most democracies, a universal authentication system permits citizens to interact with government, reducing transaction cost and increasing the trust in governments at the same time. Moreover, it is a step toward an e-election in these countries where, like in the United States, the turnout rate has become critical. Without a universal and secured authentication system, any reform of the election in the country would be very difficult to put in place.

Overall, the tangible and intangible cost of not having a national authentication system is very high.

Conclusion

The United States is one of the very few democracies that has no standardized universal identification system. The social cost is very significant. The new technologies today can make it possible to protect the system from abuse. There is no zero-sum game in a society. Opponents of such kind of authentication system are wrong and their arguments would not hold today anymore. “Information does not kill people; people kill people” as Dennis Bailey wrote in The open Society Paradox. It is time to create a single, secure and standardized national-level ID to replace the patchwork of de facto paper documents currently in use in the United States. An incremental implementation of an Estonian-like system with a possible opting-out solution like Canadian approach can be an appropriate answer to the opponents of a national authentication system in the United States.

Bibliography

1/ The Privacy Advocates – Colin J. Bennett, The MIT Press, 2008.

2/ The Open Society Paradox – Dennis Bailey, Brassey’s Inc., 2004.

3/ The Limits of Privacy – Amitai Etzioni, Basic Books, 1999.

4/ E-Estonia: The power and potential of digital identity – Joyce Shen, 2016. https://blogs.thomsonreuters.com/answerson/e-estonia-power-potential-digital-identity/

5/ E-Authentication Best Practices for Government – Keir Breitenfeld, 2011. http://www.govtech.com/pcio/articles/E-Authentification-Best-Practices-for-Government.html

6/ My life under Estonia’s digital government – Charles Brett, 2015. https://www.theregister.co.uk/2015/06/02/estonia/

7/ Hello Aadhaar, Goodbye Privacy – Jean Drèze, 2017. https://thewire.in/government/hello-aadhaar-goodbye-privacy