Can fake data be good?

By Anonymous | June 20, 2022

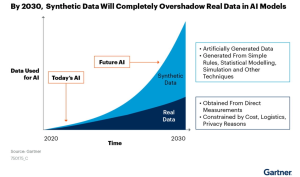

With the chaos caused by deep fake videos in recent years, can fake generated data also do good? Apparently yes, synthetic data has been playing an important role in machine learning in recent years. Many in the AI industry even think that using synthetic data will become more commonplace than using real data as techniques to generate synthetic data improve.

And there’s an ever growing list of new companies that focus on technology to generate all kinds of synthetic data (Devaux 2022). An interesting, albeit a bit creepy example, is the https://thispersondoesnotexist.com/ website that generates a realistic, photo-like image of a person that does not actually exist. Below image contains example images from that site.

This article provides a brief overview of synthetic data and its uses. For more details, refer to the Towards Data Science podcast on synthetic data that much of this information originates from.

What is synthetic data?

Synthetic data is data generated by an algorithm instead of collected from the real world (Devaux 2021). Depending on the use case the data is generated for, it can have different properties from its source data. Even though it’s generated, the statistics behind it are based on real world data so that its predictive value remains intact.

You can also generate synthetic data from simulations of the real world. For example, self-driving vehicles require a lot of data to run safely. And sometimes it’s difficult to come by, not to mention unethical to create, situations that it would need to be aware of like an accident (Devaux 2022). By simulating such incidents, you can generate data about them without endangering anyone.

Why synthetic data?

Synthetic data has many use cases from nefarious actors generating deep fake videos to more positive use cases like augmenting data collected from the real world if for example the dataset is too small or limited in some way (Andrews 2022). By far one of the more touted reasons for using synthetic data is privacy protection and speed of development.

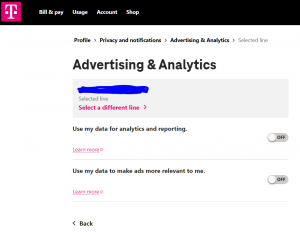

Privacy is a huge factor in using synthetic data instead of real world data. Data from industries like finance, medicine and other sensitive areas aren’t readily available and have a lot of hurdles to go through to get access. But synthetic data generated from the mathematical properties of those data do not need protection because they don’t reveal anything about the individuals in the original dataset.

This brings me to the next reason for using synthetic data which is the efficiency with which researchers can get access to data. Often real world data is either buried in privacy and security restrictions or expensive and time consuming to collect and transform properly. Synthetic data provides an alternative to that without losing the predictive power of the original data.

Another useful way to use synthetic data is to test AI systems. As regulators and companies alike use AI more in their products and businesses, they need a way to test those systems without violating privacy. Synthetic data provides a good alternative.

Challenges of synthetic data

Overfitting is one of the challenges of generating synthetic data. This can happen if you generate a large synthetic dataset from a small real world dataset. Because the pool of source data is limited, the model you create from the synthetic data will usually overfit to the characteristics in that smaller dataset. In extreme cases this can lead to a model memorizing some specific individual data which violates privacy completely. There are techniques like detecting and removing data that’s too similar between the generated and source datasets or removing data points that are outliers that help prevent overfitting.

Another big challenge is bias. If you’re unaware of a bias in the original dataset, generating another dataset from that original will just duplicate that bias. In some cases, it can even exacerbate the bias if the generated dataset is much larger than the original. There are a lot of tools and currently a lot of work going on in the field to detect and prevent bias in data.

Conclusion

Synthetic data is becoming a mainstay of machine learning. It provides a way to continue to innovate despite the difficulty of collecting real data while still protecting the privacy of the individuals in the original data. Even though there are still big challenges in using these techniques, it seems using synthetic data will continue to be a growing part of AI development.

References

- Andrews, G. (2022, May 19). What Is Synthetic Data? | NVIDIA Blogs. NVIDIA Blog. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/2021/06/08/what-is-synthetic-data/

- Devaux, E. (2021, December 15). Introduction to privacy-preserving synthetic data – Statice. Medium. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://medium.com/statice/introduction-to-privacy-preserving-synthetic-data-f5bccbdb8e0c

- Devaux, E. (2022, January 7). List of synthetic data startups and companies — 2021. Medium. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://elise-deux.medium.com/the-list-of-synthetic-data-companies-2021-5aa246265b42

- Hao, K. (2021, June 14). These creepy fake humans herald a new age in AI. MIT Technology Review. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/06/11/1026135/ai-synthetic-data/

- Harris, J. (2022, May 21). Synthetic data could change everything – Towards Data Science. Medium. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://towardsdatascience.com/synthetic-data-could-change-everything-fde91c470a5b

- Somers, M. (2020, July 21). Deepfakes, explained. MIT Sloan. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/deepfakes-explained

- Watson, A. (2022, March 24). How to Generate Synthetic Data: Tools and Techniques to Create Interchangeable Datasets. Gretel.Ai. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://gretel.ai/blog/how-to-generate-synthetic-data-tools-and-techniques-to-create-interchangeable-datasets#:%7E:text=Synthetic%20data%20is%20artificially%20annotated,learning%20dataset%20with%20additional%20examples.

Image References

- Wang, P. (n.d.). [Human faces generated by AI]. Thispersondoesnotexist.com. https://imgix.bustle.com/inverse/4b/17/8f/0e/cf91/4506/99c7/e6a491c5d4ac/these-people-are-not-real–they-were-produced-by-our-generator-that-allows-control-over-different-a.png?w=710&h=426&fit=max&auto=format%2Ccompress&q=50&dpr=2

- Andrews, G. (2022, May 19). What Is Synthetic Data? | NVIDIA Blogs. NVIDIA Blog. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/2021/06/08/what-is-synthetic-data/