Is Netflix’s Recommendation Algorithm Making You Depressed?

Mohith Subbarao | June 30, 2022

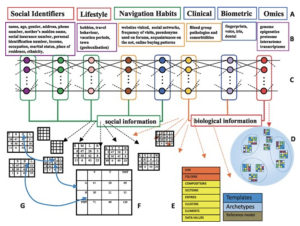

Netflix’s sophisticated yet unethical recommendation algorithm keeps hundreds of millions of people momentarily happy but perpetually depressed. Netflix binge-watching is ubiquitous in modern-day society. The normalcy of this practice makes it all the more imperative to understand the ethics of an algorithm that affects millions of people in seemingly innocuous ways. Before understanding the long-term negative effects of such an algorithm, it is important to understand how the algorithm works. Netflix’s algorithm pairs aggregate information about contents’ popularity and audience along with a specific consumer’s viewing history, ratings, time of day during viewing, devices used, and length of watching time. Using this information, the algorithm ranks your preferred content and puts it in row format for easy-watching. It is important to note that this is an intentionally vague summary from Netflix as the specifics of the algorithm has famously been kept under wraps.

Despite the secrecy, or maybe because of it, the algorithm has been massively successful. Netflix has researched that consumers take roughly a minute to decide on content on Netflix before deciding to not use the service, and so the algorithm is chiefly responsible for retention of customers. They have found that roughly eighty percent of content watched on Netflix can directly be linked to the success of the recommendation algorithm. The Chief Product Officer Neil Hunt went as far as to say that they believed the algorithm was worth over a billion dollars to Netflix. It is fair to say that the algorithm keeps users momentarily happy by constantly giving them a new piece of content to enjoy, but the long-term effects of this algorithm may not be as rosy.

A peer-reviewed research paper conducted at the University of Gujrat, Pakistan investigated these long-term negative effects. They gathered over a thousand people with a range of age, gender, education, and marital status and found that the average hours of streaming content watched was ~4 hours, with over thirty-five percent of the people watching over 7 hours a day. From this alone, it provided correlatory credence to the success of the Netflix algorithm. The research paper found statistically significant correlations between the amount of time spent binge-watching television with depression, anxiety, stress, loneliness, and insomnia. While more experimental research would be needed to provide evidence for causation, a correlational study alone with such significant effects raises eyebrows. These findings show that the success of Netflix’s recommendation algorithm has been correlated with a host of mental health issues.

These findings beg an ethical question – is Netflix’s recommendation algorithm actually unethical? To have a framework to answer such a question, we can use the principle of Beneficence from the Belmont Report. The Principle of Beneficence states that any research should aim to maximize possible benefits and minimize potential harms; furthermore, the research should consider these in both the short-term and the long-term. While Netflix is a for-profit company, their recommendation algorithm still falls under the umbrella term of research; thus, it can be fairly assessed using this principle. Netflix may increase short-term benefits for customers, such as a dopamine rush and/or an enjoyable evening with family. However, the algorithm’s intention to increase binge-watching patterns increases the potential harm of long-term mental illness for its customers. Therefore, it can be argued that Netflix’s recommendation algorithm does not meet the ethical standards of beneficence and may truly be causing harm to millions. It is important as a society to hold these companies accountable and take a closer eye to its practices and effects on humanity at large.

________________

APA References

Lubin, Gas (2016). How Netflix will someday know exactly what you want to watch as soon as you turn your TV on. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-netflix-recommendations-work-2016-9

McAlone, Nathan (2016). Why Netflix thinks its personalized recommendation engine is worth $1 billion per year. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/netflix-recommendation-engine-worth-1-billion-per-year-2016-6

Netflix (2022). How Netflix’s Recommendations System Works. https://help.netflix.com/en/node/100639

Raza, S. H., Yousaf, M., Sohail, F., Munawar, R., Ogadimma, E. C., & Siang, J. (2021). Investigating Binge-Watching Adverse Mental Health Outcomes During Covid-19 Pandemic: Moderating Role of Screen Time for Web Series Using Online Streaming. Psychology research and behavior management, 14, 1615–1629. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S328416

The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1979). The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. Retrieved May 19, 2022 from https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/the-belmont-report-508c_FINAL.pdf

Wagner, David (2015). Geekend: Binge Watching TV A Sign Of Depression?

https://www.informationweek.com/it-life/geekend-binge-watching-tv-a-sign-of-depression-