Is someone listening to my conversation with my doctor?

Radia Abdul Wahab | July 5, 2022

Literature has shown that 43.9% of the U.S. medical offices have adopted either full or partial EHR systems by 2009 [1] . Every time we visit the doctor, either in the office or virtually; a series of sensitive information is recorded. This includes but is not limited to demographic, health problems, medications, progress notes, medical history and lab data information [3]. Lab data information itself may not seem sensitive. However, as genome sequencing is becoming more and more within our reach, a lot of the lab data now includes genomic information.

On the other hand, by use of social media and other online tools, large amounts of information are continuously being voluntarily shared on the internet by us as individuals. This poses a huge risk of re-identification.

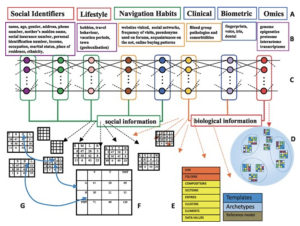

Additionally, by using mobile health monitoring devices for us to track our health and well-being, we are adding yet another flood of private health information into more databases. Figure 1 below shows a wheel of various sources of information.

All this information together with emerging technologies of web sniffing/crawling, along with information sciences, pose a huge challenge for patient/individual information privacy.

Figure 1: Sources of Health Information we share using our mobile devices [2]

Who has access to my data?

As more and more data is being collected and digitized, there is a tendency to manage large big-data databases, in order to enhance scientific assessment. The government and various corporations have also made a lot of data available with an intention for scientific enhancement. Oftentimes these are accessible fully on public websites, or by a minimum payment.

Is Re-identification really possible?

Various forms of information are collected when we go to the Doctor. These include but are not limited to, Identifier attributes (such as name, SSN), Quasi-Identifier attributes (such as gender, zip code) or sensitive attributes (such as disease conditions or genomic data). Most of the time, this data is “sanitized” and removed before being available to external parties [3].

“when an attacker possesses a small amount of (possibly inaccurate) information from healthcare-related sources, and associate such information with publicly-accessible information from online sources, how likely the attacker would be able to discover the identity of the targeted patient, and what the potential privacy risks are.” [3].

One of the most critical misunderstandings we have is that it is not possible to link information from one source with information from a different source. However, with the advent of modern technologies, it has become quite easy for algorithms to crawl across various web pages and consolidate information.

Another area of risk is that a lot of algorithms are using “smart” techniques, in order to bridge gaps between missing or inaccurate information. Below (Figure 2) is a schematic that shows a case study of such an algorithm.

Figure 2: Re-identification using various web sources. [3]

What is the process of Re-identification?

There are three main steps of re-identification: Attribution, Inference and Aggregation. Attribution is when sensitive or identifiable information is collected from online sources. Inference is when additional information is either “fitted” to that, or learned by algorithms. Aggregation is when various sources of information are aggregated together. These three steps provide quite a clear path to re-identification. Figure 3 below shows some aspects of these processes.

Figure 3: Process of Re-identification [4]

Conclusion

With the flood of health information entering the web, and with emerging technologies, almost no aspect of our health is really concealable. It is very important for us to minimize sharing of our information on the web, to the extent possible, since there is a lot more out there that we will never know of. There are smart technologies out there that are reaching in, and listening to all of these, and these may be used against us by adversaries.

References:

[1] Hsiao CJ, Hing E, Socey TC, Cai B: Electronic medical record/electronic health record systems of office-based physicians: United States, 2009, and preliminary 2010 state estimates. National Center for Health Statistics Health E-stat 2010.

[2] Isma Masood ,1 Yongli Wang,1 Ali Daud,2 Naif Radi Aljohani,3 and Hassan Dawood4: Towards Smart Healthcare: Patient Data Privacy and Security in Sensor-Cloud Infrastructure. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Volume 2018, Article ID 2143897

[3] Fengjun Li, Xukai Zou, Peng Liu & Jake Y Chen: New threats to health data privacy. BMC Bioinformatics volume 12, Article number: S7 (2011)

[4] Lucia Bianchi, Pietro Liò: Opportunities for community awareness platforms in personal genomics and bioinformatics education. Briefings in Bioinformatics, Volume 18, Issue 6, November 2017, Pages 1082–1090, https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbw078