Lived Experts Are Essential Collaborators for Impactful Data Work

By Alissa Stover | February 18, 2022

Imagine you are a researcher working in a state agency that administers assistance programs (like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, a.k.a. TANF, a.k.a. cash welfare). Let’s assume you are in an agency that values using data to guide program decision-making, so you have support of leadership and access to the data you need. How might you go about your research?

If we consider a greatly simplified process, you would probably start with talking to agency decision-makers about their highest-priority questions. You’d figure out which ones might benefit from the help of a data-savvy researcher like you. You might then go see what data is available to you, query it, and dive into your analyses. You’d discuss your findings with other analysts, agency leadership, and maybe other staff along the way. Maybe at the end you’d summarize your findings in a report or just dive into another project. Along the way, you want to do good, you want to help the people the agency serves. And despite the fact that the process here captures little of the complexity of the real, iterative steps researchers go through, it is accurate in the fact that at no point in this process did the researcher engage actual program participants in identifying and prioritizing problems and going about solving them. Although some researchers might be able to incorporate the perspectives of program participants into their analyses by collecting additional qualitative data from them, the vast majority of researchers do not work with program participants as collaborators in research.

A growing number of researchers recognize the value of participatory research, or directly engaging with those most affected by the issue at hand (and thus have lived expertise) [11]. Rather than only including the end-user as a research “subject”, lived experts are seen as having as co-owners of the research with real decision-making power. In our example, the researcher might work with program participants and front-line staff in figuring out what problem to solve. What better way to do “good” by someone than to ask what they actually need, and then do it? How easily can we do harm if we are ignoring those most affected by a problem when trying to solve it? [2]

Doing research using data does not mean you are an unbiased actor; every researcher brings their own perspective into the work and without including other points of view will blindly replicate structural injustices in their work [6]. Working with people who have direct experience with the issue at hand brings a contextual understanding that can improve the quality of research and is essential for understanding potential privacy harms [7]. For example, actually living the experience of being excluded can help uncover where there might be biases in data from under- or over-representation in a dataset [1]. Lived experts bring a lens that can improve practices around data collection and processing and ultimately result in higher quality information [8].

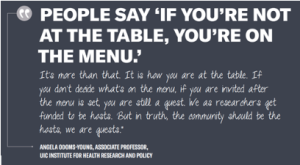

But does collaboration equal consultation? Not really. What really makes participatory research an act of co-creation is power sharing. As Sascha Costanza-Chock puts it, “Don’t start by building a new table; start by coming to the table.” Rather than going to the community to ask them to participate in pre-determined research activities, our researcher could go to the community and ask what they should focus on and how to go about doing the work [3].

Doing community-led research is hard. It takes resources and a lot of self-reflection and inner work on the part of the researcher. Many individuals who might be potential change-makers in this research face barriers to engagement that stem from traumatic experiences with researchers in the past and feelings of vulnerability [5]. Revealingly, many researchers who publish about their participatory research findings don’t even credit the contributions of nonacademic collaborators [9].

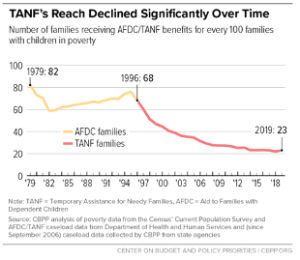

Despite the challenges, community-led research could be a pathway to true change in social justice efforts. In our TANF agency example, the status quo is a system that serves a diminishing proportion of families in poverty and does not provide enough assistance to truly help families escape poverty despite decades of research focused on this program asking “What works?” for program participants [10]. Many efforts to improve the programs with data have upheld the status quo or have even made the situation even worse for families [4].

Participatory research is not a panacea. Deep changes in our social fabric requires cultural and policy change on a large scale. However, a commitment to holding oneself accountable to the end-user of a system and choosing to co-create knowledge with them could be a small way individual researchers create change in their own immediate context.

References

[1] Buolamwini, J. and Gebru, T. (2018). Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 81:1-15. Accessed at: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a/buolamwini18a.pdf

[2] Chicago Beyond. (2019). Why Am I Always Beyond Researched?: A guidebook for community organizations, researchers, and funders to help us get from insufficient understanding to more authentic truth. Chicago Beyond. Accessed at: https://chicagobeyond.org/researchequity/

[3] Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. MIT Press. Accessed at: https://design-justice.pubpub.org/

[4] Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating inequality: how high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. First edition. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

[5] Grayson, J., Doerr, M. and Yu, J. (2020). Developing pathways for community-led research with big data: a content analysis of stakeholder interviews. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(76). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00589-7

[6] Jurgenson, N. (2014). View From Nowhere. The New Inquiry. Accessed at: https://thenewinquiry.com/view-from-nowhere/

[7] Nissenbaum, H.F. (2011). A Contextual Approach to Privacy Online. Daedalus 140:4 (Fall 2011), 32-48. Accessed at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2567042

[8] Ruberg, B. and Ruelos, S. (2020). Data for Queer Lives: How LGBTQ Gender and Sexuality Identities Challenge Norms of Demographics. Big Data & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720933286

[9] Sarna-Wojcicki, D., Perret, M., Eitzel, M.V., and Fortmann, L. (2017). Where Are the Missing Coauthors? Authorship Practices in Participatory Research. Rural Sociology, 82(4):713-746. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00589-7

[10] Pavetti, L. and Safawi, A. (2021). TANF Cash Assistance Helps Families, But Program Is Not the Success Some Claim. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Accessed at: https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-cash-assistance-helps-families-but-program-is-not-the-success

[11] Vaughn, L. M., and Jacquez, F. (2020). Participatory Research Methods – Choice Points in the Research Process. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.13244