Streamlining US Customs during a state of emergency

By Anonymous | March 27, 2020

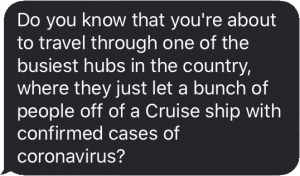

I was one of those people traveling internationally when the US government started closing borders in response to the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Apple News was bombarding my phone with dramatic headlines about flight cancelations and horrendous lines at US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) crossings, interwoven with constant reminders to avoid crowded areas. My airline and every other business I deal with had sent emails about disruptions in service and overwhelmed customer service hotlines.

Privacy is important to me, so I tend not to install unnecessary apps on my phone. In the anxiety-filled 24 hours leading up to my return flight I ignored my inhibitions and loaded every app that might help me along the way: airlines, banking, cellular provider, video downloads. I turned on additional push notifications (a feature I rarely enable) from Apple News and email accounts. The additional information blasts from news outlets, service providers, and concerned relatives did little to calm my nerves.

As the plane taxied to the runway and everyone finished cleaning their surroundings with anti-bacterial wipes, a lovely stranger told me about the Mobile Passport app that I could download to skip some lines at customs. Upon landing I downloaded the app, blindly accepted the Terms of Service, and proceded (with a cringe) to enter some of my most personally identifiable information: name, date of birth, sex, citizenship, and a clear photo of my face. I answered the basic customs declaration questionaire on my phone and sent it off to CBP before deboarding.

WHAT IS MOBILE PASSPORT CONTROL?

Mobile Passport Control (MPC) is the first process utilizing authorized apps to streamline a traveler’s arrival into the United States. It is currently available to U.S. citizens and Canadian visitors. Eligible travelers voluntarily submit their passport information and answers to inspection-related questions to CBP via a smartphone or tablet app prior to inspection.

I noticed that the app developer was not a government organization, and at the time I didn’t care. I wanted any advantage to make my connecting flight.

When I arrived at US customs I felt that much of my anxiety was unfounded. There were no significant lines and nobody in hazmat suits checking traveler’s temperatures. There was a dedicated line for Mobile Passport users, allowing me to avoid the clusters of touch-screen kiosks where most people filled out their declaration forms. After ten days quarantined without symptoms, I remain thankful that I did not have to touch those kiosks.

Upon a post-acceptance review of the Mobile Passport privacy policy I remain comfortable using this service on an as-needed basis. That is to say: I have deleted it from my phone, and will likely re-install it for future travel. Thanks to the clear and concise policy that includes GDPR specific requirements, a few important observations stand out:

1. The service provider uses de-identified information for targeted advertising from third party providers, yet offers a paid version that is ad-free.

2. Personally identifiable information (PII) is transmitted according to the respective requirements of CBP and TSA.

3. Transaction logs are pseudonymized. The customer’s name and passport number are not retained in association with form submission data.

4. Personal account data can be deleted upon request, however the pseudinymized access logs cannot be deleted because they have already been de-identified.

5. Device identifiers, which are commonly used for cross-app tracking, are not stored by the service provider.

While I’m not a fan of targeted advertising, I am willing to endure it for the convenience afforded by Mobile Passport. I assume that means Google and Facebook will learn a bit more about me from advertising analytics, but the fact that the app is not collecting the device identifiers suggests that they will not using my information in an aggregated manner. The fact that they acknowledge their inability to remove pseudinymized data provides a bit of comfort.

I’ve considered looking into the CBP and TSA policies to see what they have to say about my personal information, but going down the rabbit hole of the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Data Management Hub didn’t seem worth the stress. It was refreshing to see that DHS clearly publishes privacy impact assessments for their various programs, so depending on how long it takes for this pandemic to subside I may still end up jumping into that hole.