Digital Product Placement: The new target

Simran Sachdev | June 23, 2022

Big Brother is watching – you invited him in. The prevalence of big tech and constant collection of personal data during every online interaction and on every virtual platform has led to increased targeting of ads. This targeting has now even invaded our favorite TV shows and movies. But when does targeted advertising and data collection cross the line of privacy invasion and what measures are being put in place to protect you, the consumer?

[5]

[5]

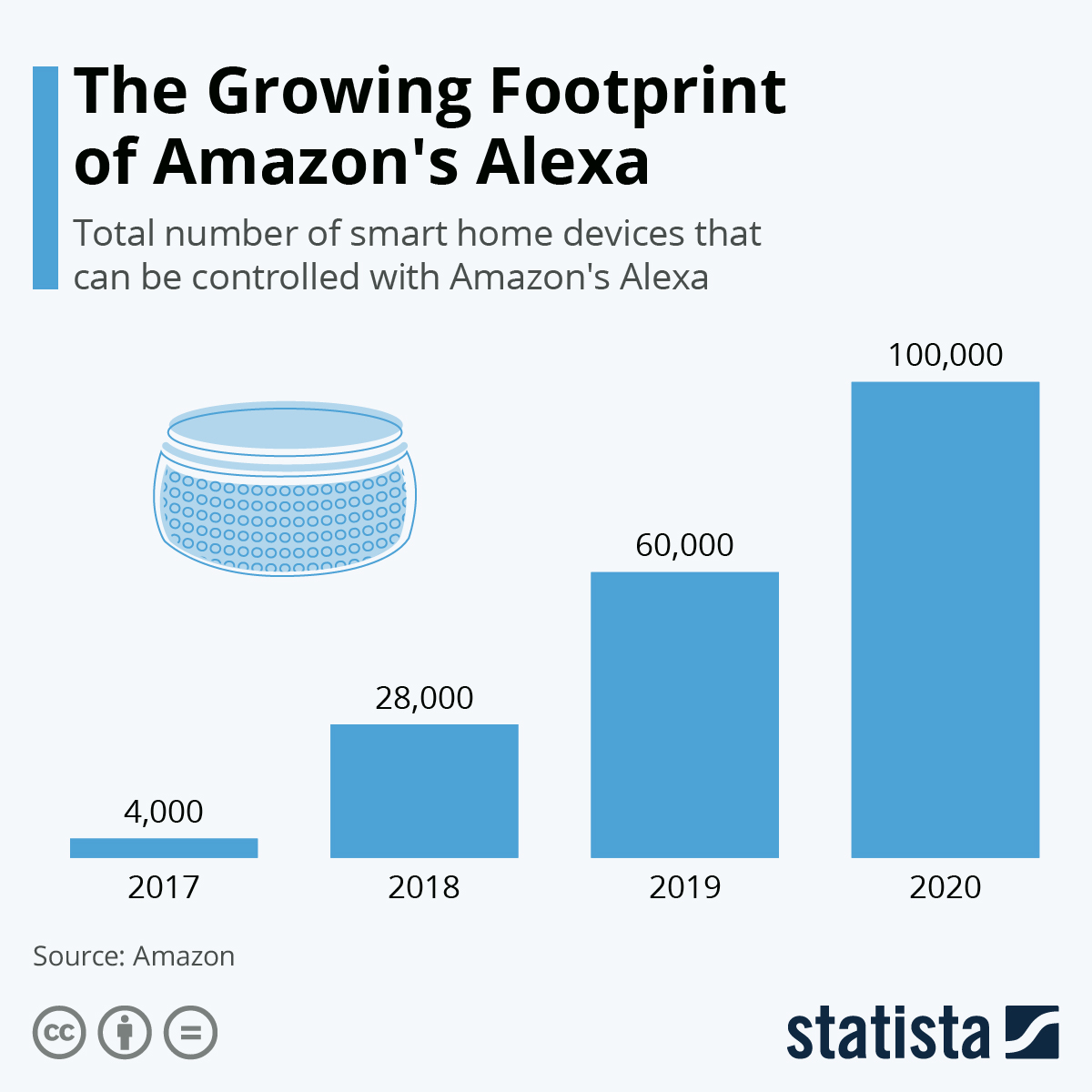

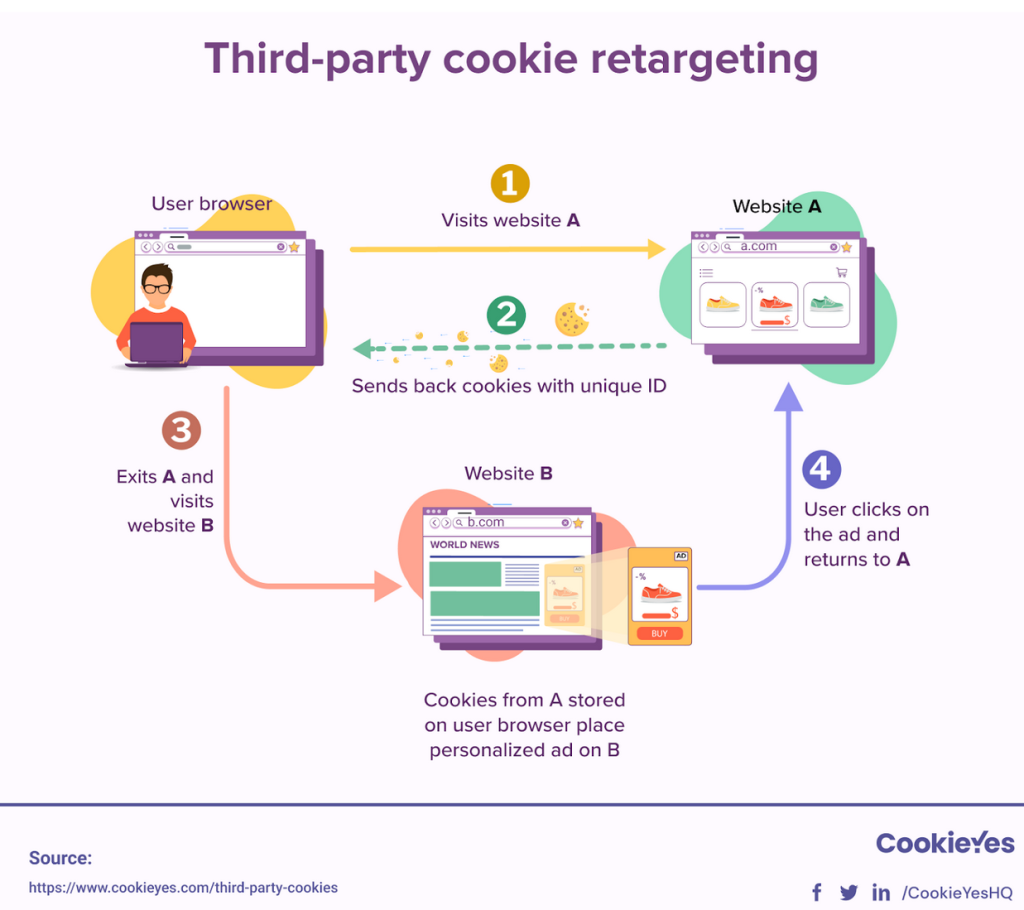

If you have ever seen an ad online that relates to your specific traits, interests, or browsing history, then you are a victim of targeted advertising. These advertisements appear while scrolling through social media, browsing a website, or streaming your favorite show and are curated based off of the user’s personal data. Artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies are becoming more prevalent in the digital advertising space and help deliver personalized content to targeted users. Digital ad spending is expected to be over $500 billion in 2022 [1]. Why is so much money being spent in this form of advertising? Well, by understanding the user’s likes and dislikes, their demographics, and their past searches, targeted ads make consumers 91% more likely to purchase an item [1].

Using consumer data to create targeted ads is a violation of their privacy. There is a lack of transparency between the consumer and the advertiser as the advertiser does obtain informed consent to use the consumer’s personal information in such a targeted way. By tracking your online usage, what products you buy, and learning the sites you visit consumers feel intruded upon. Depending on the platform, these targeted ads put consumers in a filter bubble, showing them only specific content and isolating them from alternative views and material [2]. This invasion of privacy continues to spread across online platforms, manipulating consumers in new ways.

Digital Product Placement

The latest addition to the realm of target advertising is digital product placement. With the rise of ad-blockers and increased popularity of streaming services, it is becoming increasingly difficult for advertisers to reach a large audience. With technology developed by the UK company Mirriad, major entertainment companies are using AI to directly insert digital product displays into movies and TV shows. The AI analyzes scenes that have already been filmed to find a place where an ad can subtly be inserted [3]. This can be in the form of posters on walls, buildings, and buses and even as 3D objects such as a soda can or a bag of chips. Mirriad and other technology companies are now working on technology that would tailor placed products to the viewer. Multiple versions of each ad scene would be produced so different viewers would see different advertised products.

[6] An episode of “How I Met Your Mother” from 2007 was rerun in 2011 with a digitally inserted cover of “Zoo Keeper” to promote the movie’s release.

[6] An episode of “How I Met Your Mother” from 2007 was rerun in 2011 with a digitally inserted cover of “Zoo Keeper” to promote the movie’s release.

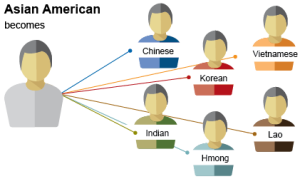

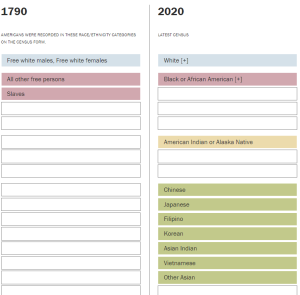

This becomes another form of targeted advertising as the ad the viewer sees is based on a combination of their browsing and viewing history as well as their demographic data online such as their age, gender, ethnicity, and location [4]. Using this data the AI system now knows who is watching, removing the guesswork from advertising. For example, an active or athletic person watching a show may see a Gatorade in the scene, while at the same time a more inactive, sedentary viewer would be shown a can of Pepsi. This becomes an additional revenue stream for streaming giants but at what cost to the user? While the AI works to subtly insert ads, there is no guarantee that it will always be able to do so without ruining the viewer’s experience. Tailoring these ads to individual viewers leads to a form of deception to the viewers by not being fully transparent on how their data is being collected and used, and by not informing them of how they will be marketed to. This changes the streaming experience for everyone by making them feel more vulnerable of having a narrowing viewpoint. From fear of receiving contrasting targeted ads from their friends, personalized digital product placement may change how one conducts themselves online in order to prevent seeing different content.

AI technologies will soon be integrated into all avenues of advertising, allowing for the creation of personalized content for everyone. Yet it also brings to light data privacy concerns. With this growing use of personalized content it is necessary to update marketing rules to include digital product placements, but also update privacy frameworks to control for the increased use of user data to target ads.

References

[1] Froehlich, Nik. “Council Post: The Truth in User Privacy and Targeted Ads.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 25 Feb. 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2022/02/24/the-truth-in-user-privacy-and-targeted-ads/?sh=42e548b4355e.

[2] Staff (2017). How Filter Bubbles Distort Reality: Everything You Need to Know. Farnam Street Blog. https://fs.blog/2017/07/filter-bubbles

[3] Lu, Donna. “Ai Is Digitally Pasting Products into Your Favorite Films and TV.” Mirriad, 1 Mar. 2022, https://www.mirriad.com/insights/ai-is-digitally-pasting-products-into-your-favorite-films-and-tv/.

[4] “Advertisers Can Digitally Add Product Placements in TV and Movies – Tailored to Your Digital Footprint | CBC Radio.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 31 Jan. 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-jan-31-2020-1.5447280/advertisers-can-digitally-add-product-placements-in-tv-and-movies-tailored-to-your-digital-footprint-1.5447284.

[5]https://www.globalreach.com/global-reach-media/blog/2021/08/11/targeted-advertising-101