Privacy in the Workplace Metaverse of Madness

Anonymous | July 7, 2022

The privacy implications of the metaverse in the workplace must be thoroughly understood and addressed before it becomes our new reality.

What is the Metaverse?

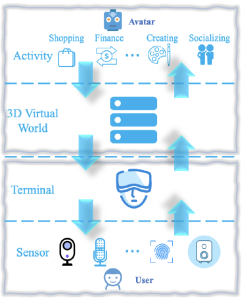

First coined by Neal Stephenson in his novel Snow Crash, the metaverse was a virtual reality escape for those living in a dystopian society, whose physical representations were replaced by avatars.

What was once just an idea based in science fiction is now becoming a virtual reality. Across the professional landscape, rather than promoting it as an escape from reality as shown in the immensely popular game VR Chat, technology companies are racing to infiltrate the corporate world with promises of efficiency never seen before and innovative collaboration experiences.

Paving the Way for Remote Work

According to Ladders, “25% of all professional jobs in North America will be remote by end of next year”.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced employers to reconsider which roles in their companies need to be in person. It has also precipitated what is referred to as the Great Resignation – employees taking a step back to reassess what is important in life and making drastic career decisions as a result. This shift to remote work is forcing companies to get creative in how they can optimize the experience while also ensuring accountability. It’s no surprise that the metaverse fits nicely into this equation.

Whose metaverse pool will you be swimming in? Will you dip your toe in the water with augmented reality? Or will you dive head first into an immersive virtual reality? The choice may depend on your employer, several of whom have already created the Metaverse Standards Forum.

Privacy Implications

Regardless of how immersive the experience is, be it a pair of glasses worn around the office to facilitate virtual collaboration or a headset you wear while in your pajamas on the couch, they all share similar implications when it comes to your privacy. Shoulder surfing may be a thing of the past as employers will get a front-row view of your experience.

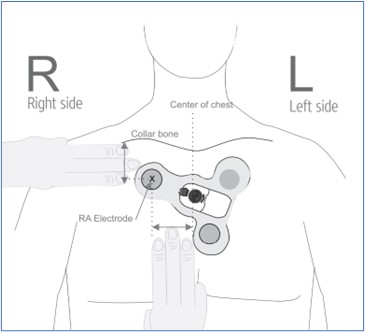

The metaverse implementations and policies are still evolving, but we can look to Meta’s Horizon Workrooms as an example of how companies may address privacy concerns going forward. Horizon Workrooms leverages the Meta Quest headset to provide companies with the ability for their workers to collaborate with each other in a virtual reality environment.

If we overlay Solove’s Taxonomy of Privacy on top of the Quest’s privacy policy, we can get a better understanding of the true scope of impact for the risks to individual privacy that will need to be balanced with the increase in collaboration and accessibility.

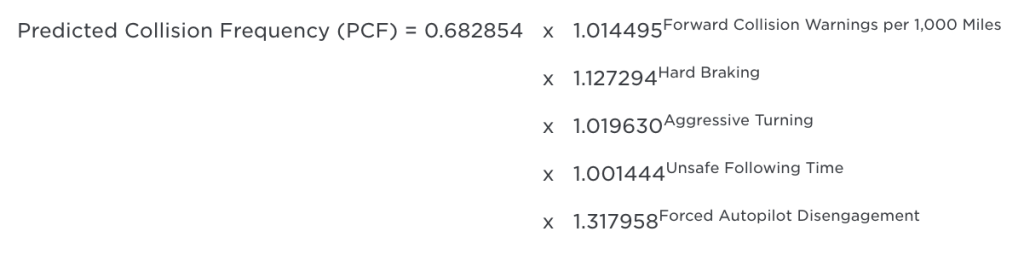

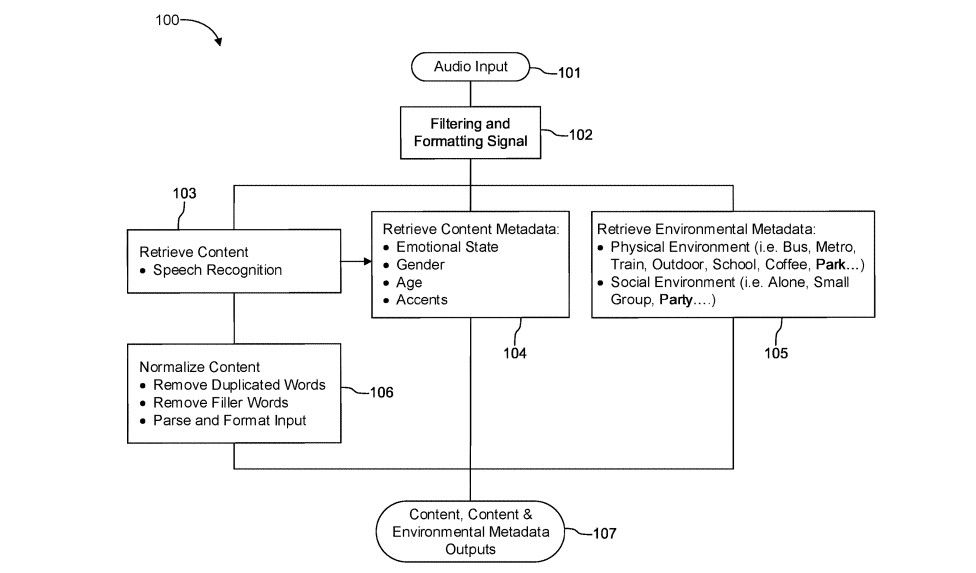

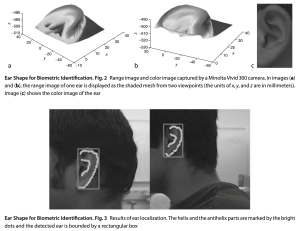

In this virtual workroom, the employee, and those they interact with, are under constant surveillance in a way that could not be practically implemented in years past. Cameras already exist in the workplace but are limited in the level of detail they capture. The Quest collects additional data points not regularly seen in privacy policies, including physical features, how the subject moves in a physical space, and detailed speech. The observed and recorded dimensions of personal privacy have expanded beyond observations from an imperfect third-person perspective, to high-quality first-person. Layering artificial intelligence on top of this data, aggregated with both quantitative and qualitative output of employees, can be enticing to efficiency obsessed employers.

Given the sensitive nature of the data at a level of detail incapable in years past, this information could be valuable not just to the company in its never-ending effort to increase profits via employee efficiency, but also serve as a foundation for psychological analysis and behavior research – not to mention pose a serious security risk by nefarious individuals or organizations seeking to gain a competitive advantage or compromising material.

Within the Quest’s privacy policy, they explicitly state that there are secondary uses for this information, such as for the improvement of speech recognition systems. While created in 1974, the Belmont Report retains its relevance even when considering such modern innovations. If and when the improvements to these systems are made, who will be the beneficiaries of such advancements? Per the report’s principle of Justice, the policy could go farther into how this data could be leveraged to improve the lives of those with speech or language disabilities, rather than only those privileged enough to be able to afford one of these devices.

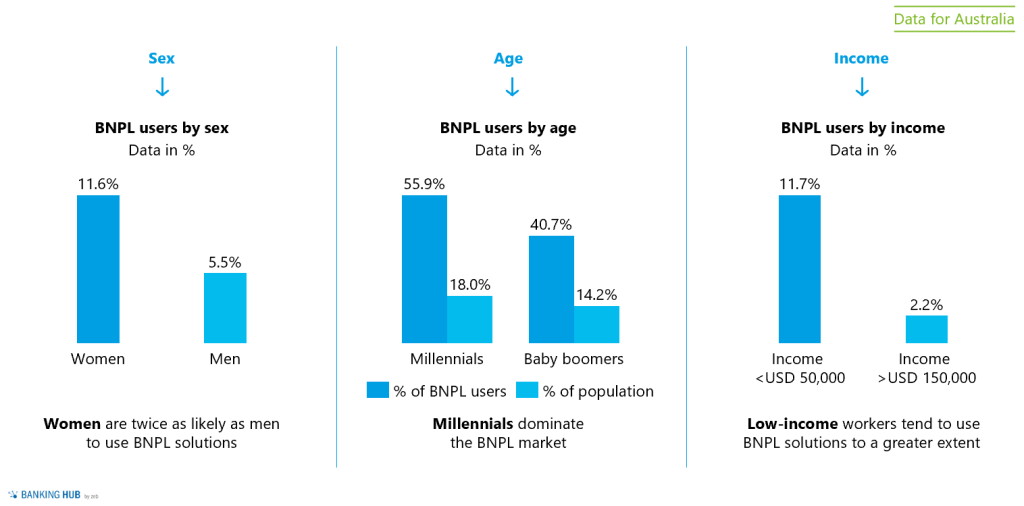

While the metaverse can close physical gaps between employees to facilitate global collaboration, this increase in accessibility introduces new challenges. In the United States of America, the Americans with Disabilities Act has protected those with disabilities and ensured them a safe and productive workplace. Additional protections for those potentially disadvantaged by the use of these devices would need to be evaluated to address accessibility concerns.

It would also be reasonable to assume this is a shared device that not only an employee could use within Horizon Workrooms, but their children for their favorite game. The privacy policy does not explicitly differentiate the collection of data from different users at the device level versus the application level. There is a risk of information dissemination of those without the autonomy to consent.

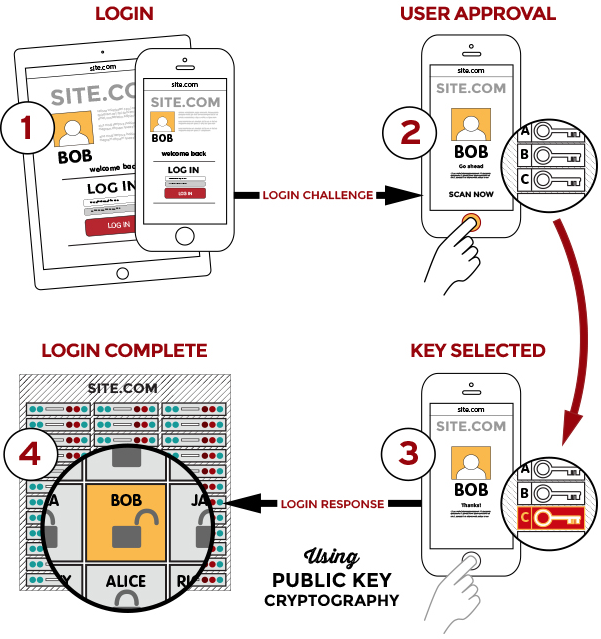

The Meta Quest policy also states that they collect identifying information to ensure the safety of its users. This results in the lack of anonymity along with the other data points being collected and thus increasing the impact of information disclosure or invasion of privacy for the users. It would be reasonable to expect this type of moderation leveraging personally identifiable information to be replicated across other company’s metaverse to ensure a safe environment that encourages an overall adoption of this technology.

Proceed, with Caution

Breaking down the barriers of physical limitations by enhancing our reality, or establishing a virtual one, can help many achieve great things and has the potential to further innovation and collaboration by leaps and bounds.

And as enticing as that may be, the privacy implications of the metaverse cannot be an afterthought in its implementation. This would necessitate the slowdown of technological advancement to ensure proper caution is exercised. Unfortunately, this may not be an option as competition for the arbiter of the metaverse heats up in order to get their share of a multi-trillion dollar market.