Operation Neptune Spear

By Chris Sanchez | March 3, 2019

Almost eight years ago on May 2nd, 2011, at 11:35pm Eastern Time, former President Barak Obama unfolded Operation NEPTUNE SPEAR to the world:

*“…the United States has conducted an operation that killed Osama bin Laden, the leader of al-Qaeda, and a terrorist who’s responsible for the murder of thousands of innocent men, women, and children.”*

Neptune Spear Command Center

At the time, the American public was aware that the US was engaged in combat operations in Afghanistan, but the whereabouts of Osama bin Laden—including whether he was alive or dead—were unknown. The announcement by President Obama (which, by the way, interrupted my viewing of America’s Funniest Home Videos, confirmed to the American public that Osama bin Laden:

- Survived the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

- Had been hiding in Pakistan for several years.

- Was killed in the raid by a highly trained (but undisclosed) US military unit.

President Obama’s announcement and subsequent reporting provided additional details about the raid and the decisions leading up to it, but the primary substance of the event can be neatly summarized in the above three bullet points. Yet much to my shock and dismay, over the coming days, I watched as news channels reported leaked details of the event to include classified information such as the identity of the military unit responsible for the raid including their call signs, identifying features, and deployment rotation cycle. None of this disclosed information materially altered the narrative of what had happened or provided any particularly useful insight into this classified military operation.

Secrecy and representative democracy have long had a tumultuous relationship, which is not likely to significantly improve in our Age of Information (On-Demand), as there will always be a trade-off between government transparency and the desire to keep certain pieces of information hidden from the public in the name of national security to include economic, diplomatic, and physical security. And though it often takes major headline events—Pentagon Papers (1971), Wikileaks (2006), Edward Snowden (2013) —to jar the public consciousness, the resultant public discussion surrounding these events, often finds that the balance between transparency and secrecy is either not well monitored, or well understood, by those who are elected/appointed to safeguard both the public trust and their overall security.

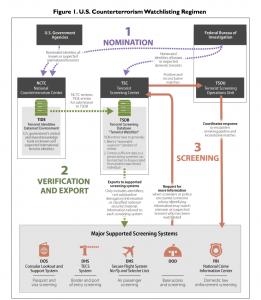

Take for instance the Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB, commonly known as the “terrorist watchlist”). The TSDB is managed by the Terrorist Screening Center, a multi-agency organization created in 2003 by presidential directive, in response to the lack of intelligence sharing across governmental agencies prior to the September 11 terrorist attacks. People—both US citizens and foreigners—who are known or suspected of having terrorist organization affiliations are placed into the TSDB, along with unique personal identifiers, including in some cases, biometric information. This central repository of information is then exported across federal agencies (Department of States, Department of Homeland Security, Department of Defense, etc.) to aid in terrorist identification across passive and active channels.

TSDB Nomination Regimen

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks and subsequent domestic terror incidents, one would be hard pressed to argue that the TSDB is not a useful and necessary information-sharing tool for US Law Enforcement and other agencies responsible for domestic security. But like other instances of the government claiming the necessity of secrecy in the name of national security, there are indications that the secrecy/transparency balance is tilted in favor of unnecessary secrecy. A report in 2014 from the Intercept —an award-winning news organization—claimed evidence that 280,000 people in the TSDB (almost half the total number at the time), had no known terrorist group affiliation. How or why were these unaffiliated people placed into this federal database? The consequences of being placed in the TSDB are not trivial. Depending on the circumstances, TSDB members can find themselves on the “no-fly list”, have visas denied, be subjected to enhanced screenings at various checkpoints, and find their personal information (including biometric information) exposed across multiple organizations.

With an average of over 1,600 daily nominations to the TSDB, I am hard-pressed to believe that due diligence is conducted on all of those names, despite what is claimed on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s FAQ section of their Terrorist Screening Center website, regarding the thoroughness of the TSDB nomination process. Furthermore, once nominated, it’s very cumbersome for individuals to correct or remove records about them in the TSDB, in spite of a formal appeals procedures as mandated by the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2014. The Office of the Inspector General under the Department of Justice has criticized the maintainers of the TSDB for “…frequent errors and being slow to respond to complaints”. A 2007 Inspector General report found a 38% error rate in a 105 name sample from the TSDB.

As long as we live in a representative democracy that values individual privacy, free and open discussion of policy, and the applicability of Constitutional principles to all US citizens, there will always be “friction” at the nexus of government responsibility, public trust in governmental institutions, and secrecy. Trust in US governmental institutions has slowly eroded over time, due in large part to the access of information previously hidden from the public, which was found to be contrary/misleading to what they had been told or had been led to believe. Experience has shown that publicly elected representatives are often not enough of a check on the power of government agencies to strike an appropriate balance between secrecy and transparency. Fortunately, though not perfect in their efforts to right perceived wrongs, much progress has been made at this nexus point by public advocacy organizations, academic institutions, investigative journalism, constitutional lawyers, and concerned citizens.

In my experience, which includes being on the front lines of the War on Terror from 2007-2013, the men and women who comprise the totality of “government institutions”, while imperfect, generally do have the best interests of the nation (as a whole), in mind when prosecuting their responsibilities. Given the limitations of human decision making in times of both crisis and tranquility, there is a tendency to err on the side of secrecy in the name of security. However, taken to extremes this mentality can result in significant abuses of power ranging from moderate invasions of privacy to severe abuses of personal freedoms. To compound the situation, the public erosion of trust in government creates a certain level of suspicion behind every governmental action that is not completely “above board”, even when there are very good reasons for non-public disclosure of information (such as the operational details as described in the Operation Neptune example cited at the beginning of this article). At the end of the day, the government will take those measures it deems as necessary to secure the safety of its citizenry, even if such actions come at the expense of the rights of minority groups or those who do not find themselves in political power. I think it’s our job as vigilant citizens to ensure that the balance of power is restored once the real or perceived crisis has passed.

How transparent does a government need to be? In a representative democracy it needs to be as transparent as possible without compromising public safety and security. How the US government and its citizens decide to strike that balance over the coming generations will be an interesting discussion indeed.

Primary Sources

1. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Remarks_by_the_President_on_Osama_bin_Laden

2. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/terror/R44678.pdf

3. https://theintercept.com/2014/08/05/watch-commander/

4. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/terrorist-screening-center-frequently-asked-questions.pdf/view