Privacy in Communications in Three Acts. Starring

Alice, Bob, and Eve

By Mike Frazzini

Act 1: Alice, Bob, and Setting the Communications Stage

Meet Alice and Bob, two adults who wish to communicate privately. We are not sure why or what they wish to communicate privately, but either would say it’s none of our business. OK. Well, lets hope they are making good decisions, and assess if their wish for private communication is even possible. If it is possible, how it could be done, and what are some of the legal implications? We set the stage with a model of communications. A highly useful choice would be the Shannon-Weaver Model of Communications, which was created in 1948 when Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver wrote the article “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” that appeared in the Bell System Technical

Journal. This article, and particularly Claude Shannon , are considered founding thought leaders of information theory and studies. The model is shown in the diagram below:

Image: Shannon-Weaver Model, Image Credit: http://www.wlgcommunication.com/what_is

Playing the role of Sender will be Alice, Bob will be the Receiver, and the other key parts of the model we will focus on are the message and the channel. The message is simply the communication Alice and Bob wish to exchange, and the channel is how they exchange it, which could take many forms. The channel could be the air if Alice and Bob are right next to each other in a park and speaking the message, or the channel could be the modern examples of text, messenger, and/or email services on the Internet.

Act 2: Channel and Message Privacy, and Eve the Eavesdropper

So, Alice and Bob wish to communicate privately. How is this possible? Referring to the model, this would require that the message Alice and Bob communicate only be accessed and understood by them, and only them, from sending to receipt, through the communication channel. With respect to access, whether the channel is a foot of air between Alice and Bob on a park bench, or a modern global communications network, we should never assume the channel is privately accessible to only Alice and Bob. There is always risk that a third party has access to the channel and the message – from what might be recorded and overheard on the park bench, to a communications company monitoring a channel for operational quality, to the U.S. government accessing and collecting all domestic and global communications on all major communications channels like the whistleblower Edward Snowden reported.

If we assume that there is a third party, let’s call them Eve, and Eve is able to access the channel and the message, it becomes much more challenging to achieve the desired private communications. How can this be achieved? Alice and Bob can use an amazing practice for rendering information secret for only the authorized parties. This amazing practice is called cryptography. There are many types and techniques in cryptography, the most popular being encryption, but the approach is conceptually similar and involves “scrambling” a message into nonsense that can then only be understood by authorized parties.

Cryptography provides a way that Alice and Bob can exchange a message that only they can fully decode. Cryptography would prevent Eve from understanding the message between Alice and Bob, even if Eve had access to it.

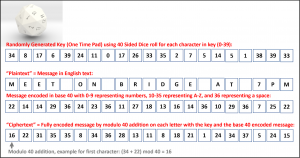

To illustrate cryptography, let’s suppose Alice and Bob use an unbreakable form of cryptography, called a One Time Pad (OTP). This is a relatively simple method where Alice and Bob would pre-generate a completely random string of characters, then securely and secretly share this string called a key. One way they might do this is using a 40-sided dice with a number on each side representing each of 40 characters they might use in their message; the numbers 0-9, the 26 letters of the English alphabet A-Z, and 4 additional characters to represent a space among others. They would assign all of the characters a sequential number as well. They could then do modular arithmetic to encode the message with the random key:

Image: OTP Example, Image Credit: Mike Frazzini

Act 3: What have Alice and Bob Wrought? Legal Implications of Private Communications

So now that we have shown that it certainly is technically possible – and it is also mathematically provable – for Alice and Bob to engage in private communications, we create a tempest of legal questions that we will now attempt to provide some high level resolution. The first big question is on the legality of Alice and Bob in engaging in private communications. We will approach this question from the standpoint of a fully democratic and free society, and specifically of the United States, since many countries have not even established de facto, let alone de jure, full democracies including protections for freedom of speech.

We can address this in two parts; the question of the legality and protections of communications on the channel, including the aspects of monitoring and interception of communications; and the question of the legality of using cryptographic methods to protect the privacy of communications. In the United States, there are a number of foundational legal rights, statutes, and case law precedents, from the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protecting against “unwarranted search and seizure,” to the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, to U.S. Code Chapter 119, that all generally protect privacy of communications, including protection from monitoring and interception of communications. However, this legal doctrine also defines conditions where monitoring and interception may be warranted. And as we have also presented, in at least the one case reported by Edward Snowden, there was widespread unwarranted abuse of the monitoring and interception of communications by the U.S. government, with indefinite retention for future analysis. So, given these scenarios, and then including all the commercial and other third parties that may have access to the communication channel and message, Alice and Bob are wise to assume their may be eavesdropping on their communication channel and message.

Regarding the question of the legality of using cryptographic methods to protect the privacy of communications in the U.S., there does not appear to be any law generally preventing consumer use of cryptographic methods domestically. There are a myriad of acceptable use and licensing restrictions, based in U.S. statute, such as the case of the FCC part 97 rules that prohibit cryptography over public ham radio networks. It is also likely that many communications providers have terms and conditions, as well as commercial law based contracts, that restrict or prohibit use of certain high-strength cryptographic methods. Alice and Bob would be wise to be aware and understand these before they use high strength cryptography.

There are also export laws within the U.S. that address certain types and methods of strong cryptography. There is legislation pending and relevant case law precedents that restrict cryptography as well. In response to the strengthening of technology platform cryptography, like that recently done by Apple and Google, and referred to by the U.S. law enforcement community as “going dark,” a senate bill was introduced by Senators Diane Feinstein and Richard Burr to require “back-door” access for law enforcement which would render the cryptography ineffective. This has not yet become law, however there has been several examples of lower court and state and local jurisdictions requiring people to reveal their secret keys so messages could be unencrypted by law enforcement. This is despite the Fifth Amendment protections of the U.S. Constitution for self-incrimination.

Of course, there are many scenarios where information itself, and/or communication of information, can constitute a criminal act (actus reus). Examples of this include threats, perjury, and conspiracy. So, again, we hope Alice and Bob are making good choices, since their communications – and the information transmitted therin – could certainly be illegal, even if the privacy of their communications itself is not illegal.