Thick Data: ethnography trumps data science by Michael Diamond

“It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.” William Carlos Williams

As business continues to pivot on its data-obsessed axis, with a fixation on the concrete and measurable, we are in danger of missing true meaning and insight from what surrounds us. The field of ethnography, established long before the bright sparks of data science were kindled, provides some language to enlighten our path, guide us through the thickets of information, and situate the analytics with new perspectives.

Drawing on his field-work in Morocco, the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz introduced the world to “thick descriptions” in the 1970’s in the context of ethnography, borrowing from the work of a British philosopher Gilbert Ryle who used the term to unpack the work of language and thought. Ethnographers, who study human culture and society, need to hack through a path to insight like a hike though an overgrown jungle. Thick descriptions are, in Geertz’s words, the “multiplicity of complex conceptual structures, many of them superimposed upon or knotted into one another, which are at once strange, irregular, and inexplicit.”

For today’s ethnographers, and the business consultants who champion these methodologies, thick description has morphed in to thick data. Consultant Christian Madsjberg contrasts this with the “thin data” that consumes the work of data scientists, and which he portrays as simply “the clicks and choices and likes that characterize the reductionist versions of ourselves.” What thin data lacks is context — the rich overlay of impressions, feelings, cultural associations, family and tribal affinities, societal shifts — the less measurable or unseen aspects that frame and inform our orientation towards the world we experience.

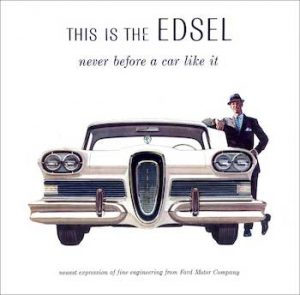

Businesses, or at least the products they launch, die miserably every day for the lack of what is found in this thick data. The story of Ford’s introduction of the Edsel is instructive.

In 1945 Henry Ford II took over the auto manufacturer that his grandfather had founded at the turn of the twentieth-century. By the 1930s and 1940s Ford’s growth had slowed and the business reputation was waning. Henry Ford immediately set out to professionalize the management team with modern scientific principles of organization. Bringing together the finest minds from the war effort and from rival companies like General Motors, Ford hired executives with Harvard MBAs and recruited the “whiz kids” from Statistical Control, a management science operation within the Army Air Force. The senior management team wrestled over strategy and organization and pored over the data – commissioning multiple research studies and building elaborate demand forecasting models. They ultimately concluded that what Ford needed was a new line of cars – pitched to the upwardly-mobile young professional family. The data and analysis identified a gap in the product portfolio, an area where Ford under-served the market demand and a place where their rival General Motors showed growing strength.

The much heralded “Edsel” launched on September 4, 1957 with a commitment from over 1,000 newly established dealerships. Within weeks it was clear that the public was turning against the product and the brand never gained traction with its target market. Described by one critic as “fabulously overpriced jukeboxes,” the Edsel came to represent everything that was wrong with the flash and excess of Detroit. Within two years Ford had abandoned the business and Edsel had become a watchword for a failed and misguided project. With over $250mm invested and no sign of the projected 200,000 unit sales in sight, the last Edsel rolled off the production line on November 20, 1959.

Ford missed the cultural moment.

Looking back, Ford’s statisticians and planners missed a series of cultural moments – the thick data that was hidden from their analysis and models. First, there was an emerging sense of fiscal responsibility, as car-buyers increasingly saw vehicles coming out of Detroit as gas-guzzling dinosaurs belonging to an earlier era, an idea that was successfully exploited by one of the best selling cars that season: American Motors’ more fuel-efficient “Rambler.” Second, the deepening sense that America was falling behind the rest of the world culturally and scientifically, that participating in the American Dream was not quite as glamorous as once believed, a sense heightened with the deep psychic impact felt across America when the Soviet Sputnik went into orbit in October 1957. Third, the beginning of a consumer movement against the product-oriented “build it and they will buy” approach to marketing — a concern, captured in the same year as the Edsel launched, with the publication of Vance Packard’s _Hidden Persuaders_ that exposed the manipulation and psychological tactics used by big business and their Madison Avenue advertising agencies; and an approach to marketing that was roundly and succinctly critiqued a few years later in Theodore Levitt’s seminal 1960 essay Marketing Myopia.

Lessons for history.

The Edsel may be one of the best known business failures before the age of Coca Cola’s New Coke, or McDonald’s Arch Deluxe, but it is an interesting and salient case because cars are a uniquely American form of self-expression – they announce who we are, how we see ourselves and what tribe we belong to. Indeed automakers have been described as the “grammarians of a non-verbal language”.

But these lessons about fetishizing the things that can be measured, ignoring the limits to how well we can quantify key drivers, and mistaking strong measures for true indicators of what matters most, were to have much greater consequences than an abandoned brand. Sadly they were lessons still being learnt by America as the country entered and prosecuted the War in Vietnam a decade later. Robert McNamara, one of the “whiz kids” hired by Ford who rose to be President of the company, was now leading America’s military strategy, as Secretary of Defense. His dedication to the “domino theory,” which argued that if one country came under the influence of Communism, all of the surrounding countries would soon follow suite, was the justification used to escalate and prolong one of America’s most misguided foreign interventions. And his obsession with “body count” as the key metric of the war led many to exaggerate and mislead the public.

While it is simplistic to reduce the tragedy of the War in Vietnam to one man or one concept, more than a million Vietnamese, civilian and military, died in that war and nearly 60,000 soldiers from the US lost their lives.

McNamara failed to grapple with the “thick data” of the situation because it was hard to quantify. He refused to embrace an hypothesis about the conduct of the war that differed with his own, as it would have meant pursuing a much deeper understanding and empathy for the leaders and people of South East Asia. Ultimately McNamara, by then in his 90’s, came to understand and champion “empathy” in foreign affairs. “We must try to put ourselves inside their skin and look at us through their eyes, just to understand the thoughts that lie behind their decisions and their actions.”